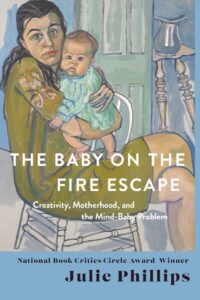

“Complete Attention to Two Things at Once.” On the Women Who Rewrote the Motherhood Plot

Julie Phillips Considers the Groundbreaking British Mother-Writers of the 1960s, from A.S. Byatt to Lorna Sage

“A change in physical relations and conditions changes mental and emotional states beyond what even the most revolutionary of reformers can begin to foresee.”

–Doris Lessing

*Article continues after advertisement“To destroy the institution [of motherhood] is not to abolish motherhood. It is to release the creation and sustenance of life into the same realm of decision, struggle, surprise, imagination, and conscious intelligence, as any other difficult, but freely chosen work.”

–Adrienne Rich

*

In Shropshire, England, in May 1960, seventeen-year-old grammar school student Lorna Sage staged a jailbreak from a maternity ward to study for her A levels. The nurses wouldn’t let her read—“We don’t feed our babies on books,” they said—so Lorna handed her newborn daughter to her own mother and took her exams, leaking milk and thinking Latin, “caught up in a kind of euphoria, scribbling for my life.”

The headmistress of her grammar school told her no university would take her, a person of low morals, no matter how good her results. But in her brilliant memoir of her lower-class childhood, Bad Blood, Lorna wrote that adults’ disapproval taught her her own value: it “fueled my conviction that I must mean something.”

Mother-writers who came of age around 1960 in Britain staged private rebellions, refusing to choose between books and babies, declining their mothers’ burdens of masochism and guilt, rewriting the motherhood plot.

They looked for support where they could find it: from husbands, from sympathetic teachers, eventually from the women’s movement that would bring them together. “It was a lot easier to have a baby than to be delivered of the mythological baggage that went with it,” Lorna Sage observed, bracing herself for a fight against all those who thought that a teenage mother of the lower classes should know her place. “From now on I was making my way against most people’s assumptions, I’d have to count my friends and fight back.”

The same year, 1960, twenty-three-year-old Antonia Susan Byatt had her hands full with a baby and a novel. What she wanted was education and children, brains and love, and so she had gone to see her graduate-thesis supervisor, the Oxford don Helen Gardner, to say she was getting married. Gardner had informed her that not only would marriage ruin her mind, it would cost her her income. As a married woman she would lose her research grant, though a married man would have his increased.

So Antonia went off in a rage and married her economist boyfriend. Like Le Guin, she was not sorry to abandon her thesis: “I truly would rather have been a writer than an academic, and I needed to be forced into making that decision.” But she was terrified of losing herself like her own mother, who after graduating from Cambridge had married, had four children, and ended up haunting her own house as a depressed, embittered femme maison. Byatt said she and her sisters all shared the determination “not to get stuck in the kitchen because you could see it had destroyed . . . something essential in our mother.”

Matrophobia (Adrienne Rich’s term for the fear of becoming one’s mother), plus a strong sense of vocation, carried Byatt through her early motherhood, when she had two children in two years. “The first baby was a total accident,” she later said. “When she was born, I did think, for a very short time—well, I called her Antonia because I thought, she’d better have the name, because now I won’t write a book. And then after a bit I just went back to writing a book. I wrote with a baby on the desk, in one of those little plastic chairs. What you have to learn to do is pay complete attention to two things at once.”

Mother-writers who came of age around 1960 in Britain staged private rebellions, refusing to choose between books and babies, declining their mothers’ burdens of masochism and guilt, rewriting the motherhood plot.As a student Byatt heard it said that Cambridge professor Elizabeth Anscombe, who was a philosopher, authority on Wittgenstein, and mother of seven children, was once so lost in thought while changing trains that she left her sleeping baby on the platform at Bletchley. It was permission-giving, the knowledge that it was possible to forget one’s children. Like the baby on the fire escape, the baby at Bletchley station is a more drastic version of the baby on the writing desk: the state of presence and forgetting that allows the work to get done.

Babies eat books, as happens literally in The Millstone, Margaret Drabble’s 1965 novel about a woman choosing single motherhood. The baby crawls into the mother’s roommate’s room and chews up several pages of her novel in progress. (Tape and retyping rescue the manuscript, though they can’t do anything for the bad reviews.) But babies create books too: The Millstone brought maternity back from its ghostly status by revealing it as a hero’s journey and a tale worth telling.

Buchi Emecheta’s 1974 Second Class Citizen did the same: its autobiographical protagonist refuses to play the roles she’s offered (loyal wife, submissive immigrant) and instead incorporates her motherhood into her writing. Emecheta was determined to become someone for her five kids, causing Alice Walker to call her admiringly “a writer because of, not in spite of, her children.”

If motherhood can make a writer fall silent, so can the pain of losing a child. In 1972, Byatt’s son, Charles, the second of her four children, was walking home from the park when he was hit by a drunk driver whose car jumped the curb. He had just turned eleven. A few days before, she had felt his warm breath on her cheek as he slept on her shoulder in the bus, and now he was gone.

Byatt was pregnant with her youngest and had just taken a job teaching at University College London to pay for her son’s school fees. She stayed on for the next eleven years, writing little. In her short story “The July Ghost,” a mother feels too rational to see apparitions, yet she longs to be haunted by her child, because it would be less unbearable than his absence. “After he died, the best hope I had, it sounds silly, was that I would go mad enough so that instead of waiting every day for him to come home from school and rattle the letter-box I might actually have the illusion of seeing or hearing him come in. [When] they said, he is dead, [I thought] is dead, that will go on and on and on till the end of time.”

Lorna got into university despite her headmistress’s warnings. When she discovered she was pregnant, she and her boyfriend, Victor Sage, had gotten married and spent the next months living at Lorna’s parents’ house, studying together for their exams, two teenagers supporting each other in their improbable determination to live a life of the mind. At her school’s speech day, the headmistress pointedly took as her theme “Be good, sweet maid, and let who will be clever,” but when Lorna crossed the stage to receive a prize her fellow pupils cheered.

Lorna and Vic applied to university together, and Lorna, because she had a husband, was promptly rejected by all the Oxbridge women’s colleges. She could have waited until she was twenty-three, when a married woman could be accepted as a “mature student,” but she was afraid that if she waited that long, she’d forget she’d ever intended to be a scholar.

Finally Durham University, moving with the changing times, dropped its prohibition on married students to admit them. They left their daughter, Sharon, with Lorna’s parents during the term, and accepted their status as “freaks” in the other students’ eyes. When they graduated together with firsts in English, they were such a novelty that the Daily Mail printed their picture, with four-year-old Sharon pouting in their arms. They both got teaching positions at the new University of East Anglia and were able to bring Sharon to live with them full-time.

Though their sex lives never recovered from the shock of the unplanned pregnancy and they eventually separated as friends, they nurtured each other’s careers as Lorna became a brilliant academic and feminist critic. Unstoppable in her eagerness to work and live, Sharon recalled, she was the kind of young mother who shows up to a parent-teacher conference dressed in full Swinging London mode. But she was also “very much in [my] corner, always.”

All these women befriended, supported, or paved the way for Angela Carter, who had her baby at forty-three, in 1983. When she did, in the wake of the sexual and feminist revolutions, a community of mothers and others gathered around her. Some had never married; some had same-sex partners; some had married but hadn’t had children; some had chosen single motherhood. They enjoyed showing Angela how it was done, the burping and the baby talk, and were pleased with themselves and with her, all together raising children, or not, on their own terms.

__________________________________________

Excerpted from The Baby on the Fire Escape. Copyright © 2022 by Julie Phillips. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.