Coming to the Realization That I Might Have PTSD

Ryan Leigh Dostie on Restlessness and Violence Post-Iraq

your ending, my beginning

Nothing really bad happened to me so I can’t have PTSD, I tell myself, and that makes sense to me. I don’t feel amiss when I come home from Iraq. The doctor said it herself. I came back better. At Fort Gordon, not only do I reconnect with my old friend Josephine, but I find Jonathan still there, my first lover, the slice of me that once was. Andres and I have parted ways for good, and Jonathan wants to get back together with me. Now, what a pretty war story that is—the soldier returns home to her former love, the flame that never died. We move in together. We even get a dog. Here’s your storybook ending, that 1950s post–World War II kind of perfection. Except it’s not.

Something is amiss right from the start, but things further deteriorate by the end of the first year. I lie in bed, staring up at the ceiling, tears rolling down my temples, choking on nothing. My eyes trace the lines of these four safe, comfortable walls and I feel nothing. Jonathan’s chest rises and falls with each soft snore, his head turned in the opposite direction. I watch that point on his chest steadily going up and down and I feel empty. I sit up, cross my legs, my hair tangled down my back, and I dig. I dig inside my memory, into my chest, trying to resurrect those old feelings I once had for him, that suffocating obsession, the way my heart used to utter and kick when Jonathan glanced in my direction. I wait for that intense need to hear his voice, the way I used to rest my head against his barracks wall and let him talk for hours, loving the inflections of his voice. I never had that with Andres, the wild desperation of a first love. I thought it was because there was no one like Jonathan, that I would never love anyone else like I did him. But I have him back now and I feel nothing.

There’s a hole here in my chest, and this has to be normal, right? This is what happens when you grow up. This is what it means to be an adult. And I turn my head just a little, unintentionally glaring at him, at the way the sheet is tucked around his shoulder and brushing his chin, the way his lower lip hangs open as he sleeps, almost like a child. I have the sudden urge to grab his shoulder and shake him awake. I want him to hug me. I want to look him in the eye and tell him he can’t hurt me anymore. He could ignore me or not. Love me, or not. There’s nothing here to break. This is ending, we both know it, but I don’t know how to drag up the emotion to care.

I slide out of bed, expertly navigating the maze of stacked books and comics on the floor, padding silently out of the room and across the house in the dark. I like the dark. It feels comfortable here where no one can see me. I can’t sleep, but I can’t tell you why. I don’t have nightmares. I dream of nothing. There is so much nothing here.

I open the door to the garage, to where that new dog sleeps. Dorian Gray raises his head, golden-brown eyes wary. I climb down the wooden steps. “Hello, there,” I coo, and fold myself onto the dog bed with him. I curl up my legs, tuck my cold feet against each other, and rest my temple against my folded hands.

Dorian watches me, ears folding down in uncertainty. Someone had starved him. Someone had beaten him. We didn’t know at first, when we took him home from the shelter, a sweet, visually stunning creature with long, full white-and-gray fur. He’s a Siberian husky, German shepherd, something else mix, and looks all wolf. But there’s no wildness in him. Beneath all that fur, his spine presses against his skin. His ribs protrude. He cowers when you toss a ball at him. He’s tentative and quiet.

I snuggle close and share his air, breathing in his out, my nose just touching his. I reach out and sink my fingers into the thick mane around his neck. He raises one white paw and leaves it on my arm. “I’m going to sleep here with you,” I tell him, and he doesn’t seem to mind. This, at least, I feel: It’s only been a few days, but this dog is mine. The world could burn, but I have my Dorian Gray.

I chase infatuations, then drop them once they’re caught, feeling powerful. I can consume everything because there’s such a divine freedom in feeling nothing.

I sigh and he lowers his head a little. “You’re going to be okay,” I promise him. I loved Dorian before he loved me, but I earn his trust through these quiet moments, through sleeping up against him on his bed in a dark, cold garage. Very soon Dorian Gray will grow back his confidence; he’ll shed his reticence. He’ll stand strong beside me, leaning against my legs for my support, not his. Dorian recovers quickly and marvelously.

I don’t.

*

Things end with Jonathan much as they did with Andres. I don’t see the common thread. Instead I bounce again from bed to bed, sprawling out on foreign sheets, blissfully detached, well versed in the worth of a body, in the weight of its limbs and the importance of sacredness, which is nothing at all, we’re all a little bit worthless, our bodies flung from here to there with little control or agency. I chase infatuations, then drop them once they’re caught, feeling powerful. I can consume everything because there’s such a divine freedom in feeling nothing. Liberty hums through my bones, splits my face into a grin; I twist men around my hands, my body fearlessly devouring, because they can’t take what I don’t have—from the married warrant officer who swears he’s separated and maybe he is but probably not, to the beautiful, blond British soldier who sings me “God Save the Queen,” naked, one arm slung behind his head while I laugh, a finger pressed against my bleeding lip from where he punched me, to the young civilian who doesn’t know what to do with me, a little cowed by my aggressiveness, my clear understanding of exactly what I want.

And through it all, I hear the cast-iron ringing of the words what if I can never love again, and I brush it off, because that was uttered by a soldier who saw things, did things, so that can’t be me. Nothing that bad really happened to me. I can’t have PTSD.

*

fight me, bitch

I leave active duty in September 2005 and return to Connecticut. I buy a small apartment in New Haven with my deployment money and live alone, just Dorian and me. My mother picked out the apartment before I even got home, because it was cheap, cute, and exactly six miles from her house. She smiles as she helps paint every room in the place. She would’ve moved me into her house if I agreed, but I didn’t, so this is close enough.

I go up to Maine to visit my father, only to arrive while he’s out. The bartender at my father’s rustic restaurant tilts his head and stares at me blankly.

“Wait, who are you again?” he asks.

“I’m Pete’s daughter,” I say.

“I didn’t know Pete had a daughter.” My stomach sinks.

“He never mentioned you,” says the bartender, and a few of the waitresses laugh.

I glance down at my bag, trying to hide the disappointment that clenches my throat. “Oh,” I say simply.

“No, I’m not being serious!” he backpedals, not realizing this is the worst joke he can make. “It’s funny because he talks about you all the time.”

I’m skeptical and it’s obvious. He tries to convince me, some of the waitresses and even the cook chime in, but I’m not sure if it’s real or pity. The bartender is forced to list my achievements—Japan, Army, Iraq, languages I speak—before I start to believe him. The idea that my father talks about me so often seems a little too good to believe.

If my father does or doesn’t, he gives no indication. He places me in one of the best rooms in his B&B, one with a quiet view of the Dead River, allows Dorian to sit in the restaurant by my feet, and, when I fuck one of his river guides nearly blind, sportively requests that I not break his men.

Fight me, bitch, I think, fists clenched, body clenched, hard. This is my rage and I am everything with it.

*

Back home in Connecticut, I party like a soldier, which is to say hard and repeatedly by civilian standards. I’ve embraced the femininity of pink and heels and lip gloss, having left my combat boots packed in the back of my closet, but I feel no loss of power. I stride with a purpose, spine straight, eyes direct. The lights of the club pulse blue and white and I twist on the dance floor, arms overhead, the hair at the nape of my neck wet with sweat. I own this floor. I am all high heels, long legs, and short skirt. My gaze doesn’t flitter away if you say you want me; I grin, because of course you do. I am a bright, burning star, always looking for more, looking for something to push back against me.

I slip easily between people, moving toward the bar, in control of my stride, my shoulders, the steady sway of my hips. I pause at the bar, one hand resting against the wood, and the man beside me slips his hand up the hem of my skirt and presses his palm against my bare ass. He does so with a smirk to the boys behind him. He doesn’t even glance at me—I’m not a woman but the punch line of a joke I haven’t been invited to.

So I punch him in the nose. My fist makes contact hard. His head snaps back, he stumbles, his hands flash up to his face, and it’s magnificent, every second is magnificent as he falls away from me. He looks at me now, stares at me with eyes wide, half his face obscured by his hands, and I grin. I want to hit him again. Fight me, bitch, I think, fists clenched, body clenched, hard. This is my rage and I am everything with it.

The man quickly points to the man beside him, to one of his friends, as if to say he did it, he did it, but I don’t care. I take a step forward because I want to hit him again. Him or his friend, I don’t care. I want to see his nose bleed. I want to hear the crack of bone. I can’t breathe around my own fire, it burns so hot that I’m blinded.

A friend grabs my elbow, trying to pull me away, but I shake off their grip, stalking toward nothing with a purpose, teeth clenched, shimmering with contained violence. I glare and people give me space, as if they can feel heat rolling off my skin. I wonder what I look like. I imagine I look glorious, like a warhorse dancing across the battle field.

I’m sexually aggressive. I crook a finger, take a lover home, and flip him off me, us both tumbling off the bed and hitting the floor. I land on top, every time.

“Whoa,” he breathes, eyes a little wide, a little startled.

“Yeah,” I say, all teeth. “Whoa.” One hand is clamped around his throat. I clench, lean down, and tease his lower lip with my teeth, staring, glaring. He likes it. I like it. I like me on top.

I feel no fear anymore, as if the emotion has been sliced out of my brain. I walk at night, late at night, two or three in the morning, headphones brazenly pressed against my ears, following the banner of Dorian Gray’s white fluffy tail. I walk shadier sections of New Haven because I can’t sleep, my brain running, running, running, never stopping. I like to stretch my legs when everyone else is asleep, when the streets are black and quiet. I like the music loud in my skull. But mostly I like the potential for violence—the slightest edge where something probably won’t happen, but could happen. I thrive in that possibility. It feels like home.

I imagine an attempted rape while I walk here in the dark, where men think to violate me and I envision each try ending with brutality as I thwart them, again and again, each fantasy a shock of lovely adrenaline, as if I can rewrite my own narrative, begging for it to happen again so I can revise how it ended, give myself the happily ever after. I imagine myself ripping my would-be rapist to bits and pieces and leaving clumps of flesh and body parts on the pavement.

There’s no place for this kind of rage in civilian life. I expected it to stay behind in Iraq, or unpeel from my skin when the time came, along with the uniform.

I dream of violence. I imagine being targeted and turning with feral glee. I’d rip at ears, those come off with minimal force; impale eyeballs with thumbs, I hear they pop like grapes. I’d wrap strong legs around a waist and bury teeth into the neck, into the carotid artery. The power in the human jaw is truly something amazing—265 pounds of force. The body, when committed, can offer such remarkable viciousness. It’s a beautiful bit of machinery. I feel rage in my hands; they want raw violence, not the kind behind a gun but with fingers and nails and muscles. I want to break bones and feel them crack under my palms.

There’s no place for this kind of rage in civilian life. I expected it to stay behind in Iraq, or unpeel from my skin when the time came, along with the uniform. Civilian life is quiet. Mundane. I have nothing to be angry at, but I’m still angry. The boredom and safety enrage me. I’m part of the stereotype—the angry soldier, standing over a body outside some bar, knuckles white and red, mouth black with a wordless scream. I should mind it, I know something has to be wrong, except everything feels right, like I’m perpetually high, brain-devouring endorphins making my body tingle. It’s a potent emotion—feeling in power instead of out of it. The only problem is my dreams aren’t listening to the rest of me. They’re not empty anymore. They’ve morphed into nightmares and they disturb what little sleep I manage.

I’m in the sand, huddled against a thorny bush, hands dragging through the silt, nails digging into the rock bed as mortars sing and crash overhead, but I can’t find my M16, hands grasping at nothing, heart pounding. I’m crawling through the dirt, cringing with each explosion, screaming, calling my weapon by name, as if it will respond and come home, but I can’t find my fucking M16, and when I wake, gripping sheets soaked with sweat, I still can’t find it. My hands are still empty. And it hurts.

Or there is the recurrent dream where I am both soldier and insurgent, two bodies at once, staring down the barrel of an M16, staring up the barrel of an M16, huddled against a stone wall, feeling trapped and helpless at one end of the rifle, and also standing, rifle tucked into the shoulder and with the superiority of holding metal and gunpowder in my hands. There’s the fear of dying on one side, the fear of killing on the other, one of us hisses, “Die,” the other screams, “No!,” the crack of a shot and we both live and die, the sensation of life draining from the body, while also being simultaneously victorious, standing over the dead me, finally having done what I am trained to do. They say you can’t die in your dreams, but I’ve done it over and over again, felt that death, the terror of staring up into the black hole of a muzzle. That narrow little barrel becomes my entire existence, too large to escape from, impossible to look away.

I think I can ignore the nightmares, or the inability to fall asleep, or to stay asleep. I can do this. When I do finally sleep, I doze late into the morning, into the afternoon, and it seems like a reasonable trade. I can write late into the evenings anyway, shifting everything around. It’s okay. I can do this.

__________________________________

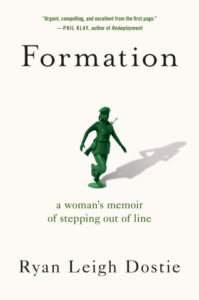

Excerpted from Formation. Used with permission of Grand Central Publishing. Copyright © 2019 by Ryan Leigh Dostie.

Ryan Leigh Dostie

Ryan Leigh Dostie is a novelist turned soldier turned novelist. As an Army Persian-Farsi/Dari Linguist in Military Intelligence, she was deployed to Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom I and II (2003-2004). She holds an MFA in fiction writing and a bachelor’s degree in History from Southern Connecticut State University. She lives in New Haven, Connecticut, with her husband, her wondrously wild daughter, and one very large Alaskan Malamute. Formation is her first book.