for my father

Only rivers bottom out like this.

Only rivers bottom out with this kind of conviction.

Not humans, or, at least, not humans as

indisputably human as you were,

trapped in consciousness’s surplus, exilic,

animalized absurdity, writhing in its contradictions—

you, the shyest person we hardly ever knew,

the solitary we hardly ever knew.

You the fatalist. Your favorite sentence

“It is what it is.” (Yes, it is, it really is.)

Only the negative constructions pertain with you.

Nothing to allegorize or ring changes on

with you. Nothing occluded. Nothing with which

to make analogies or metaphors.

Never not meaning what you said, never not transparent.

Never could you have been like this river,

acquiescent to, and companionable with, Earth,

supple, reconciled, patient

while trapped between the high banks,

narrowing itself, widening itself,

sinuous through the industrial places—

slag heaps on either side, coal barges booming down its waters—

and placid and fructifying among the farms.

Never you with dynamics like this,

rushing limpid from the foothills;

so-singing in the valleys;

oozing, opaque, mercuric through the marshland,

silvery, satiny, emollient, satised;

the rippling and dissimulating liquid medium—

not apparent to the flesh like you but the illusory

reflective surface into which we fall and drown.

Don’t even imagine the flexibilities,

the insinuations, the dragon and the serpent

and the river beside which

you nursed that despair the three of us who loved you best

could never coax you away from.

The cold but intact rainbow trout under the ripples

are doing what? Feeding? Dreaming? No.

They are concentrating. They don’t need ears

to hear your ghost, thrashing and muering in the brush

between the river and the road—

your ghost coming back to the place you might have

thought you should have died

(all alone were you with your disappointments)

but didn’t, your ghost afraid to go back to where you

shouldn’t have died but did. I met him up there.

We were shivering up there together. He asked me,

“How did I get here?”

“How do I get back?”

“Where do I go now?”

*

I have a friend. (You’ll be glad to know.) She and I work together. (You’ll be glad to know I still have a job.) She’s an ally. She’s sympathetic. She’s warmhearted. She’s socially conscious, gentle, a decent type, and from what I’ve observed an excellent mother, too. Not very smart, though. A little while after your soundless departure, I was telling her about you. I was describing what I saw as your place (yes, yes, your highly functional place) on the spectrum of . . . what are the right words, neurocognitive homelessness? I was describing cultures of shame evolving across millennia; economies of scarcity versus economies of surplus; civilizations teetering on the edge of time, about to take the plunge into oblivion. Deep India, I said to her. Wonders and terrors, I said to her. Deep India, strewn with elephants and cobras. Scorched by temples, mosques, stupas, churches, synagogues. Cratered with poverty, hunger and thirst, storms of affliction. Shot through with sacred rivers. They flood. They shrivel out. The sun’s furious particle stream immerses the pencil-thin scavengers picking sustenance from the dry riverbeds. The infant god opens his mouth to display the entire, appalling universe. I told her that long ago, when the Earth was still flat, you made your pinched, solitary, tramp-freighter journey from there to here—Colombo, Suez, across the Middle Sea, then over the far edge. I was talking privation; I was talking history; I was talking injustice. I was getting wound up and indignant. That was what must have triggered her inimitable gift for the sentimental non sequitur. She put her right hand on my left arm and said, “He’ll always be with you. In your heart.” See what I mean? See what I mean? Not if she had said one bright morning we’d meet up again in Heaven (and I wouldn’t put it past her to say something like that, too) would she have made me angrier. I could have kicked her shin. But (wait, don’t interrupt—and, no, of course I didn’t kick her shin) I’d like to explain why I kept talking to her in the aftermath of her idiotic outburst, why I didn’t shake the dust of my feet oat her and cut her off then and there forever. Though the time in which I’m writing this overlaps yours, you’d be amazed and embarrassed if you understood the extent to which we’re allowed these days, encouraged even, to indulge feelings and succumb to motives and express resentments and make demands offensive to reason that a mind with an experience like yours, a burden of discipline, a resignation, and a silence like yours, a mind like yours cowled by melancholy, would consider disreputable, even shocking. I’m sad to say you won’t be surprised that I’ve taken advantage of this license. I’ve indulged, openly and shamelessly—and, also, secretly—more times than I’m willing to remember. But I want you to understand that at this moment my talking was anything but self-indulgent. I was confused in the weeks after you died, and my confusion didn’t derive from the universal fact that a parent’s death is too strangely shaped for a child of theirs to grasp with any confidence but from the fact that I myself was becoming strangely shaped. I was crying (bawling at times) and grieving in the way I imagine I was expected to, in conformity with generally accepted principles of grief; but, also—don’t get judgmental; I’m prey sure I’m not alone in this—I wasn’t just feeling grief but congratulating myself for it. I was seeing myself as the star of my loss, its protagonist, treading the boards, pacing under the proscenium arch of bereavement. Some part of me was saying, “Finally, reality. I’ve heard so much about it.” That wasn’t the real strangeness, though. It was this: this sin of self-awareness, this dramatization of the self, this consequentiality of consciousness, this aestheticization, this the most pathetic of all the assertions of the self as it stumbles across its blasted heath of existence was leading to a separation of self from self that was making apparent another person underneath. Another person suddenly arrived inside me. Another person, as real as the person typing this, but detached, outside the world itself and growing huge in relation to it. Another person was standing at the crossroads of time and space, shirtless, shoeless, but dressed in a nice suit, on the outside looking in, curious but indifferent to being and not being, both of which he understood as accidental and impossible. The free person, the truly free, free from time, space, the world. Don’t roll your eyes, this was actually happening. Cool and supercilious before a million universes, Whitman says, or something like that. In the years when you were angry with me, and frightened for me, the search for this person haunted my mind. But now that I was he, he was the last person I wanted to be. The distance I suddenly had achieved wasn’t joyous. It was unendurable. This is why I kept talking and talking, whenever I could, climbing hand over hand up the rope of words to get back to my ordinary, unenlightened life. I was clinging to other people with words. I was gripping them by their lapels. I couldn’t let them go. The knowledge I had I didn’t want. I knew, though, probably for the first time in my life, what I did want. I wanted the details. I wanted to be sitting on the living-room couch, watching Jeopardy! with you.

*

I get up in the middle of the night.

I go to the bathroom and micturate.

I come back and lie in bed wide awake.

I can’t forget, I can’t forget.

In the dark room, the severed wire

sparks and sparks uselessly

that once was that living wire

we shared alone,

across which, at those few piercing moments

in all our interactions,

what we call our selves

traded places. You saw yourself

through my eyes and I saw myself

through yours. These moments ping

my optic nerves alive.

Your looking at you through me

the last time you waved goodbye,

your walker holding the storm door open,

your t-shirt loose around

your shrunken chest.

My looking at me through you

the first time you waved goodbye—

sixteen months old, my hair not cut yet,

sitting in the sunlight

on the red masonry floor,

the sun entering through the open door,

the two of us on both its sides.

And then, the two of us

looking down at our four feet

on the frozen Middle American street—

on our way

to the Saturday premiere matinee

of How the West Was Won.

I’m matching you stride for stride.

Our four feet are moving like two feet,

and we are alive.

__________________________________

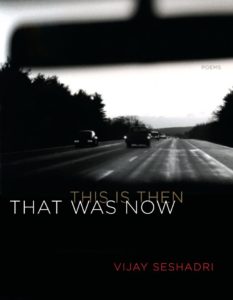

“Collins Ferry Landing” excerpted from That Was Now, This Is Then. Copyright © 2020 by Vijay Seshadri. Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org.