Collecting the Last, Lost Stories of WWII

How a Family Remembers Itself in Darker Times

PROLOGUE

December 2014

“Without families you don’t get stories.”

The woman who tells me this stands making coffee in her apartment in Amsterdam. Her name is Hesseline, Lien for short. She is over 80 and there is still a simple beauty about her: a clear complexion without noticeable makeup; a little silver watch but no other jewelry; and shiny, unpainted nails. She is brisk in manner but also somehow bohemian, dressed in a long dark gray cardigan with a flowing claret paisley scarf. Before today I have no memory of ever having met her. All the same, I know that this woman grew up with my father, who was born in the Netherlands immediately after the war. She was once part of my family, but this is no longer the case. A letter was sent and a connection was broken. Even now, nearly 30 years later, it still hurts Lien to speak of these things.

From her white open‐plan kitchen we move to the seating area, which is full of winter sunlight, filtered partly through stained glass artworks that are fitted against the panes. There are books, museum catalogs, and cultural supplements spread beneath a low glass coffee table. The furniture is modern, as are the pictures on the walls.

We speak in Dutch.

“You wrote in your email about being interested in the family history and about maybe writing a book,” she says. “Well, the family thing doesn’t really play for me. The Van Esses were important in my life for a long time, but not now. So what kind of writing do you do?”

Her tone is friendly but also businesslike. I tell her a little about my work as a professor of English Literature at Oxford University—writing scholarly books and articles on Shakespeare and Renaissance poetry—but she knows most of this already from the Internet.

“So what is your motivation?” she asks. My motivation? I’m not sure. I think hers could be a complex and interesting story. Recording these things is important, especially now, given the state of the world, with extremism again on the rise. There’s an untold story here that I don’t want to lose.

On this bright December morning we talk of world affairs, of Israel, of Dutch politics, and about the situation in Britain, where David Cameron’s coalition government is nearing the end of its five‐year term. We move quickly from subject to subject, almost as in an interview for a job.

After perhaps an hour she pushes away her empty cup and speaks definitively:

“Yes, I have faith in this. Shall we sit at the table? Do you have a notebook and pen?”

I had not wanted to arrive like a reporter, so I need to ask her for paper and something to write with, but we are soon seated at the dining table, which is made of pale laminate wood. I can ask anything I want about what she remembers: what people said and did; what she wore and what she ate; the houses she lived in; and what she dreamed.

“I think hers could be a complex and interesting story. Recording these things is important, especially now, given the state of the world, with extremism again on the rise.”

We sit in the bright, warm modernity of the apartment and our first meeting stretches on for hours. The documents—photographs, letters, various objects—appear only gradually as she thinks of them, but by midafternoon, with the light outside already fading, the table is covered in mementos. These include a children’s novel with a bright yellow cover featuring a steamboat, and a ceramic tile with a cartoon on it of a drowning man. There is also a photo album of red imitation leather that has a well‐worn spine. On the first page of the album there is a picture of a handsome couple with the words “Mamma” and “Pappa” written beneath in blue pen.

The woman on the left in the photograph is Lien’s mother, whose name is Catharine de Jong‐Spiero. She is perched on the edge of a rattan chair, the curved back of which envelops her. The sun is full in her face and she is smiling a little shyly. Her husband, Charles, Lien’s father, sits on the ground in front of her in his shirtsleeves, his large hands resting comfortably on his knees. He leans back against his wife, who has one of her hands on his shoulder, and he looks up with a confident, ironical gaze. There is an air of nonchalance about him, laughing at the idea of a posed photograph in a way that his wife, with her fixed smile, finds harder to do.

The man’s confidence is also there in a few more photographs pasted on the first page of the album. One shows him in the back of a motorcar, surrounded by a group of dapper young men. In secret he holds his fingers, like bunny ears, behind the head of the friend who poses in front of him with a pair of gloves and a cane.

In another he stands, hat in hand, in front of a large black doorway, his leg with its polished shoe thrust to the fore. There are about a dozen of these early pictures. The most crumpled of them—torn, folded, and restuck with yellowing glue—is of a beach party of twenty‐three young men and women in bathing suits, smiling and embracing. A woman in white at the center holds up what looks like a volleyball. “Mamma, Pappa, Auntie Ro, Auntie Riek, and Uncle Manie” reads the hand‐written text beneath.

Although I am unpracticed at interviewing, a rhythm soon develops to our conversation. I ask countless questions, probing away at some detail, scribbling down notes.

“What was the room like?”

“Where did the light come from?”

“What sounds could you hear?”

It is only when all the details of an episode are exhausted and she can tell me nothing further that we move on.

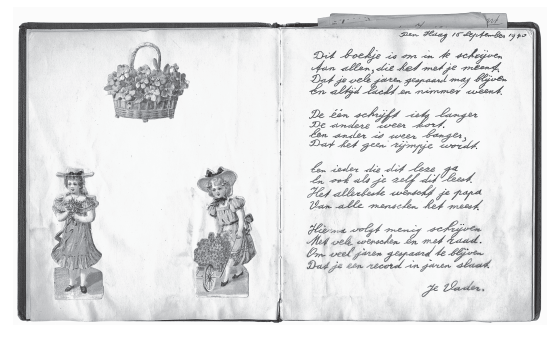

Darkness has fallen by the time that Lien mentions her poesie album: a kind of poetry scrapbook that nearly all girls in the Netherlands used to keep. At first she cannot find it, but then, after looking around in a side room, she suggests I stand on a chair and look on top of the bookshelf, where it lies wedged, kept safe from dust in a small, transparent plastic bag. It is a gray cloth album of around three by four inches with a faded pattern of flowers on the cover. Inside on the first of its facing pages there is a set of rhymes that are signed “your father” and dated “The Hague, 15 September, 1940.”

They begin as follows:

This is a little book where friends can write

Who wish for you a future bright

To keep you safe throughout the years

With many smiles and never tears.

I stand for a moment reading the sloping hand. Opposite, on the left, there are three old‐fashioned paper cut outs in pastel colors: at the top, a wicker basket of flowers; and below, two girls in straw hats. The one on the right smiles and looks happy, like Lien’s mother in the photo, but the cut out girl on the left purses her lips as she clutches her posy. She glances sideways, as if unable to meet the viewer’s eyes.

__________________________________

From The Cut Out Girl: A Story of War and Family, Lost and Found. Used with permission of Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Bart Van Es.

Bart Van Es

Bart van Es is an academician, tutor and lecturer at St Catherine's College, University of Oxford.