Colin Kaepernick: A True Dissident

How He Exposed the Sports World’s Limited Scope, Curiosity, and Critical Thinking

All voting is a sort of gaming, like chequers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it, a playing with right and wrong, with moral questions; and betting naturally accompanies it. The character of the voters is not staked. I cast my vote perchance, as I think right; but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation, therefore, never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority.

–Henry David Thoreau, “Civil Disobedience,” 1849

![]()

The date was September 27, 2016, the day after the first presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. The 49ers had completed practice at their complex in Santa Clara, and the writers gathered around Colin Kaepernick’s locker. Kaepernick told reporters that he watched “a little bit” of the debate but was hardly impressed by either Clinton or Trump.

“It was embarrassing to watch that these are our two candidates,” Kaepernick told the scrum around his locker. “Both are proven liars and it almost seems like they’re trying to debate who’s less racist. And at this point . . . you have to pick the lesser of two evils. But in the end, it’s still evil.” After the election, Kaepernick dropped an atom bomb on reporters: he hadn’t voted. The papers dug a little deeper, and it turned out that Kaepernick not only wasn’t registered to vote in 2016 but had never been registered to vote. Ever.

“You know, I think it would be hypocritical of me to vote,” Kaepernick said. “I said from the beginning I was against oppression, I was against the system of oppression. I’m not going to show support for that system. And to me, the oppressor isn’t going to allow you to vote your way out of your oppression.”

San Francisco Chronicle columnist Ann Killion felt that by not voting, Kaepernick “lost a lot of support” from people who were genuinely sympathetic to his cause, especially because several ballot measures in California—from a repeal of the death penalty to gun control to education funding—affected the communities for whom Kaepernick was fighting.

ESPN’s Stephen A. Smith, who supported Kaepernick’s right to protest, found his reveal unforgivable. “I thought it was egregious to the highest order,” Smith said, adding that Kaepernick was a “flaming hypocrite.” And George Skelton of the Los Angeles Times was obviously not in the mood for the theories of Thoreau:

What really fries me, however, is that Kaepernick—the supposed committed idealist—didn’t bother to vote Nov. 8. In fact, he didn’t even get off his butt to register to vote. He never has anywhere he lived, the Sacramento Bee reported last week. So Kaepernick is the classic hypocrite. And a bad role model. He hasn’t been connecting the dots between griping and voting to fix what he’s griping about.

Yes, he has a constitutional right to refuse to stand during the anthem. Yes, he has a right to say a pox on politics and not vote. But no, he doesn’t have a moral right to both disrespect the country and not exercise his fundamental birthright—and duty—to help change it.

And this is where the high-minded, frothy outrage, the talk of hypocrites and voting supposedly being the most important act a citizen owns sounded great in theory but, in the real world, was just another lazy talking point to discredit dissent the punditry could not handle. According to the US Elections Project, 94.2 million eligible voters—42 percent—did not vote in what was considered to be one of the most important elections in years, proof that Kaepernick wasn’t a hypocrite but that something had gone terribly wrong with our democracy. For his age group, the percentage of those not voting shot to 50.

Further, approximately 147 million voters—or 65 percent of the electorate—lived in “non-battleground states whose electoral votes were pre-ordained.” Kaepernick, a Californian, would have been one of them. In 2012, 52.9 percent of television ad spending was allocated by both parties in Florida, Ohio, and Virginia. The remaining 47.1 percent covered all the other 47 states. In 2016, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania received more ad spending than the other 46 states combined. Since the 2000 election, each presidential campaign has hinged upon essentially four states: Ohio, Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina, and in the 2016 presidential election, $1.7 billion of outside money was raised by Super PACs. Yet the sports world concluded that Kaepernick was a hypocrite for not voting in a country whose entire political system had been overrun and corrupted by money. There was no room to discuss the disaffected American voter or the place of politics or the money, not in the world of the sports machine.

“Kaepernick saw the killing and was moved by injustice, and the simple act of standing up to it scared the hell out of the white mainstream, its fans, its jock pundits, and compromised talkers, who were more comfortable with celebrating dead martyrs than dealing with live issues.”

Maybe it was all too much to ask that an industry that bathed in the cliché of “taking it one game at a time” be expected to analyze political trends and parse analytics, whether the topic was patriotism and dissent or the values and flaws of the electoral college. Maybe most of the writers were in over their heads. ESPN’s Bomani Jones was not.

“He thinks the system is busted, therefore dropping a ballot within that system isn’t going to be something that is going to change anything,” Jones said. “So, he’s adopted a different take, and the idea that he is disqualified because he didn’t vote is a lazy outlook to me because it doesn’t even bother to take a moment to appreciate where it is that he is coming from. Rather than ‘Why did you not vote?’ it was ‘How dare you not vote.’ Maybe it’s the economist in me, but the individual vote does not sway anything, and that’s the paradox of voting. It’s actually more costly to the individual than the payoff you’ll ultimately receive.”

Kaepernick had exposed the sports world’s collective limitations in scope, curiosity, and critical thinking. He also had the giants of the philosophical canon on his side. Some of the greatest theorists took the position that the true dissident should not participate in the voting process. “In any case,” wrote the French philosopher and Nobel Prize winner Jean-Paul Sartre in his 1973 essay “Elections: A Trap for Fools,” “the revolution will be drowned in the ballot boxes—which is not surprising, since they were made for that purpose.”

Like Thoreau before him, Sartre concluded that the true dissident surrenders his power to the state by participating in the political ritual that has created the very conditions for his dissidence. When Thoreau says, “Voting for the right is doing nothing for it,” he is saying that voting is the most passive of acts, the very least a person could do. More important were the actions Kaepernick had begun to undertake through community programs, putting his hands in the soil, organizing workshops, donating money. Sartre concurred with Thoreau:

Why am I going to vote? Because I have been persuaded that the only political act in my life consists of depositing my ballot in the box once every four years? But that is the very opposite of an act. I am only revealing my powerlessness and obeying the power of a party. Furthermore, the value of my vote varies according to whether I obey one party or another. For this reason the majority of the future Assembly will be based solely on a coalition, and the decisions it makes will be compromises which will in no way reflect the desires expressed by my vote.

Kaepernick could have made different choices. He could have voted. He chose not to. Yet by merely voting, other people were deemed more competent, more responsible, more engaged, more committed to the democracy just because they stuffed a ballot box and for the next four years did nothing else. In the land of systematic gerrymandering, the influence of the oil mogul Koch brothers, and Super PACs, whose billions secretly controlled state, local, and national political races and left would-be voters resigned that voting didn’t matter, Big Sports Media reached a different verdict: Colin Kaepernick was the problem.

*

Maybe it really was all a big con. Maybe Kaepernick really was just another spoiled athlete, too rich to care, someone who got lucky and found himself swept up in the zeitgeist. Maybe he closed his eyes, swung hard as he could, and, as they say in baseball when a slap hitter goes yard, “ran into one”—right into Thoreau and Sartre and MLK and all the other Big Thinkers with the Big Ideas about dissidence and civil disobedience. Maybe Kaepernick revealed, however unintentionally, that the high-minded talk of voting or not voting meant nothing compared to the billion-dollar power of the Koch brothers. Maybe all he was really trying to do, as Kaepernick’s most dismissive critics in San Francisco suggested, was impress his girlfriend, Nessa Diab. Maybe his intentions were initially good and then he discovered that he was in over his head and, as Carmelo Anthony cautioned, couldn’t turn back.

Nothing in Kaepernick’s actions during 2016, however, suggested any of this to be true. Instead, something else was happening: Kaepernick saw the killing and was moved by injustice, and the simple act of standing up to it scared the hell out of the white mainstream, its fans, its jock pundits, and compromised talkers, who were more comfortable with celebrating dead martyrs than dealing with live issues. Kaepernick exposed other black athletes to be so far removed from their roots as political figures that they had forgotten their inheritance. In his landmark book Forty Million Dollar Slaves, Bill Rhoden referred to the African American athlete as suffering from “the loss of mission.” It was Colin Kaepernick who began to return them home.

__________________________________

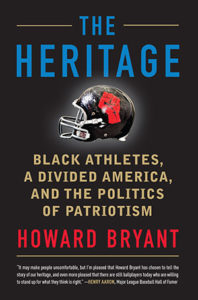

From The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism. Used with permission of Beacon Press. Copyright © 2018 by Howard Bryant.