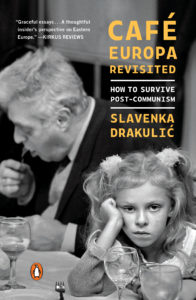

Cold War Turned Flavor War: On European Food Disparity, From East to West

Slavenka Drakulic on How Capitalism Impacts Quality in Post-Communist Countries

One morning at breakfast, while cutting a slice of dark bread and spreading butter on it, I was transported back to the 1950s, to our old kitchen in the former Yugoslavia. I was eating the very same breakfast from childhood, a slice of dark bread and butter with a spoon of jam on top. There wasn’t much else to eat back then except three kinds of bread: black, half-white and white. No fancy cornflakes, no croissants or Danish pastries. The whole family drank either coffee made of barley or chicory, with milk, or a cup of so-called black Russian tea. It was while visiting relatives in Italy in the mid-1960s that I tried a chocolate spread called Nutella for the first time; it was the finest thing I had ever tasted. Having it for breakfast was a true feast for me.

This is why, when my friend Marta from Bratislava visited me in Vienna with her six-year-old grandson, Tomasz, I served him Nutella for breakfast. He ate with great gusto, chocolate covering his fingers and a little bit on his nose.

“Grandma,” Tomasz said suddenly, “why does chocolate in Vienna taste better than the same one at home?”

To my surprise, Marta nodded.

“You are right,” she said. “Many things taste better here because, although they look the same, they are better. They are not the same as at home. See this strawberry yogurt from the supermarket here? I think it has more strawberries in it than the same brand of yogurt I buy at home.”

But the jars were just the same, he protested, how could the yogurt be different? Tomasz is a curious boy and, having tasted the difference but knowing nothing about food production and distribution in the European Union, he asked the logical question.

This brought us to the heart of a recent controversy about differences between food products in Eastern and Western Europe. The labels are the same but the content is different! Not much different, but still.

This yogurt has 40 percent more strawberries here, Marta explained.

Really? Now it was my turn to be surprised: Are you sure you are not imagining that?

But no, this is not a new thing. Many of us Slovaks, especially from Bratislava, cross the border in order to shop in a nearby town some thirty or forty kilometers away. Not only because of the prices, but because of differences like this. People just sensed that the products were not the same, but now we have proof that they are not identical. Take Iglo fish sticks, one of Tomasz’s favorite foods, something that in fact I planned to serve him for dinner. If you buy them here they contain more fish. Of course they will taste better, just like Nescafe, Coca-Cola or Milka chocolate.

I wondered if there was an end to that list.

After people complained to consumer protection agencies or in the local media, various agencies compared the products and discovered considerable differences. Not just in Slovakia, but in other Eastern European countries as well. Just when we believed that we finally have the same as them. Remember how after ’89 we visited the first big new supermarket near my apartment together, hardly believing what we saw on the shelves there?

Back then, imported goods were a form of symbolic confirmation of the successful transition to a capitalist economy.

Indeed, I remembered that the supermarket had been a big sensation compared with the small sad neighborhood shops, where it was hard to get bread if you did not get up early enough, and where cabbage and potatoes were just about the only vegetables available. But Slovakia was not that bad, Poland and Bulgaria were much worse off. There, in the late 1980s, the shelves were still lined with jars of pickled vegetables and cans of compote; milk was not easy to find in Sofia. When the very first private supermarket opened in Bucharest in the early 1990s, I watched people walking along the shelves, marveling at the products. But these times are long gone. Now every village has supermarkets full of foreign products, from cheeses to salami, from chocolate to milk products, from fish to fine vegetables wrapped in plastic. Is this not a picture of a consumer paradise that reveals the main reason people hated communism? Back then, imported goods were a form of symbolic confirmation of the successful transition to a capitalist economy. When we entered the EU, we believed it to be a community in which all citizens enjoyed an equal right to freedom; it did not occur to us that Coke and Nutella would not be of the same quality. The fact that there was no money to buy such fine food was less important, at least back then.

Someone once told me that Coca-Cola is sweeter in Slovenia. When I tasted it in order to check, it was really so. Is the company cheating us? I wondered, but dismissed such a thought as paranoid. I remember how we collected the bottles and cans when someone brought Coke from abroad and kept them as decorations. Why would the adored Coca-Cola cheat us? Nescafé somehow tasted better in Vienna too, but perhaps that was a side effect of the city’s baroque beauty.

My hairdresser in the small town in Croatia where I spend my summers tried to bring me to my senses. Once a month she drives to the first supermarket across the Italian border for a big shopping trip. It is not so much about saving money, she told me, although many products are cheaper there. It is about the difference in quality, she explained. So I buy everything, from canned tomatoes and frozen food to Coke. But I really go for washing liquids, Ariel and Persil. I have to wash a lot of towels every day and I can tell the difference if I wash them in Ariel produced in Eastern Europe or somewhere in the West.

I did not comment but thought how our people are never satisfied with what they get. Only yesterday they had nothing to buy—and now they are disappointed by a difference in quality! It looked as if she and the other people I heard telling such stories were right, but I preferred to live in denial. Admitting that we are second-class consumers would lead me straight in the direction of George Orwell’s novel Animal Farm, which describes a society in which all members are equal, but some are more equal than others. I would lose my trust in the Union, perhaps in the free market economy too.

First to take action, insisting on research and investigation in 2013, were two EU parliamentarians, Biljana Borzan from Croatia and Olga Sehnalova from the Czech Republic. In 2017, Slovakia’s consumer association tested a selection of food from supermarkets in eight EU member states: Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. In some products they found small differences—in any case, the products were not identical— but there were much bigger differences in others. They tasted different and the content was different as well, from Knorr soup to Iglo fish sticks (the latter had 58 percent fish instead of 65 percent). Slovakia’s Ministry of Agriculture drew similar conclusions when comparing twenty-two same-brand products bought in Bratislava and in two Austrian towns across the border. Half of them tasted and looked different and had different compositions. For instance, a German orange drink purchased in Bratislava contained no actual juice, unlike the same product sold in Austria, which had some amount of juice.

When other countries followed suit, they found roughly the same differences. Hungary’s food safety authority examined twenty-four products sold in both Hungary and Austria. It found, among other things, that the domestic version of Manner wafers was less crunchy (and crunchiness is just about the most important “ingredient” they offer!), and the local Nutella not as creamy as the Austrian one. Little Tomasz was right.

Someone once told me that Coca-Cola is sweeter in Slovenia. When I tasted it in order to check, it was really so. Is the company cheating us?

In Poland, Leibniz biscuits contain 5 percent butter and some palm oil, while those sold in the company’s home market of Germany contain 12 percent butter and no palm oil, a cheap alternative to butter. The Slovene consumer association examined thirty-two products sold in Slovenia and Austria and identified ten where there was a difference in quality. The point is that the inferior version of the product was always placed in an Eastern European country and never in a Western country.

Slovenian Milka chocolate was, for example, almost the same—but with an additive not present in Austrian Milka chocolate. However, you would know this only if you bothered to read the ingredients, which very few people do. So nothing is hidden; but who reads small print?

My favorite finding concerns Kotányi pepper. It sounds hilarious, but even pepper is not the same everywhere! You would not think this possible, because all Kotányi pepper is packed in one and the same factory. However, the content was still different in different countries: pepper in Slovakia and Hungary (and Austria!) was more humid than it should be. Pepper in Bulgaria had too many crushed seeds, while paprika contained only 108.9 grams of red pepper extract per kilogram compared to 140 grams per kilogram in the packet for the Austrian market.

Coca-Cola and Nescafé Gold are different too, but at least Nescafé confirmed the differences: “the recipe [. . .] differs in European markets depending on consumer preferences that differ from market to market.”

In the midst of all this research and talk about food, I was happy to see that the Czechs did not forget my Croatian hairdresser and her claim about washing liquid, or in this case washing powder. Here, the explanation they got from the producer is worth mentioning: the powder is weaker because Czechs put more of it in the washing machine.

*

The media reverberated strongly with the results of all this analysis, although it seemed to some pundits that too few sample products were tested and the differences that had been found were too small. That said, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, a major German daily newspaper, considered the results bad enough to head-line their article on the subject pig feed for eastern europeans? Other media outlets reported on Eastern Europe as being a “European garbage can”—there was no lack of imagination when it came to describing the food situation.

In Poland, Leibniz biscuits contain 5 percent butter and some palm oil, while those sold in the company’s home market of Germany contain 12 percent butter and no palm oil, a cheap alternative to butter.

Of course, the companies in question had to defend themselves and try to come up with plausible explanations. This generally boiled down to “catering to local tastes and preferences.” The U.K.-based manufacturer of Iglo fish sticks said it adapts the product to local tastes and preferences, which are not the same in Austria and Slovakia, the Czech Republic or Hungary. But this only added insult to injury, suggesting that Slovaks, Czechs, Hungarians, Poles and Croats—or the entire post-communist part of the EU—have bad taste.

What else could producers say? Certainly not the truth, that the reason for all this is that these markets are more cash- strapped and less competitive. The producers sometimes reduce the quantities of the most expensive ingredients to keep food prices affordable and still make a profit. After all, Eastern European consumers make less money than those in the West and the food they get is only a reflection of their purchasing power. According to a report by the European Trade Union Institute, the gap between pay in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic on the one hand and Germany on the other was bigger in 2018 than it had been ten years before. This means that Poles, Hungarians and Czechs have less money to spend in supermarkets on Nutella and suchlike—which is what producers are adapting to, not specific tastes in food. But it sounds better to talk about taste. In reality, producers are probably not making geographical or political choices. They could not care less about post-communist countries, transition, etc. Their only concern is profit. If the price of a fish stick is higher, nobody would buy it. The solution: less fish. Therefore, the different content is wrapped, canned or packed and named strictly the same, undoubtedly to make the impression that the content is the very same.

This explains the loss of trust in producers, despite the fact that they are not doing anything against the law. So long as the ingredients are declared, the practice is legal in the European Union. The ethics of such conduct is another matter. A 2018 opinion poll for the Czech Agriculture and Food Inspection Authority found that 88 percent of Czechs were concerned about the difference in food products for Czech and Eastern European markets, while 77 percent rejected the argument that such differences were based on local preferences. In the eyes of the victims, these differences are not only a consequence of the profit- driven logic of the market economy. When producers claim that their food product is adapted to a different taste in food, it is humiliating— it means that they consider Eastern Europeans second- class citizens. If those manufacturers explain their decisions as being linked to a cash- strapped market, it means that they think Eastern European citizens do not deserve better and should be happy with whatever they can get. Western companies have abused the hunger for all things Western that Eastern European citizens experienced after having been deprived of these things for years.

It was not long before political leaders in the region took up the subject. There was an outcry about the injustices committed by the “old” Europe toward its new member states in the East; meetings were held with the European Commission in Brussels, and strict measures demanded. EU Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality Vĕra Jourová, a Czech, said: “Dual quality of food products of the same brand in the member states is misleading, intolerable and unfair to consumers. I will do my best to stop it.” Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán called the food scandal unethical, while Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov went as far as to call it “food apartheid.”

What else could producers say? Certainly not the truth, that the reason for all this is that these markets are more cash- strapped and less competitive.

The logic of capitalist production was then turned into a political issue. The unequal quality of food offered a good platform for the nationalist populism of Eastern European leaders, who saw their chance to stir up anti-EU feelings. Nothing can provide more wrath or pride than food. The Visegrád Group, or V4, a political alliance of Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, briefed the biggest nationalists, who used the test results and opinion polls to demand justice from Brussels and show voters they were defending their interests against EU elites.

__________________________________

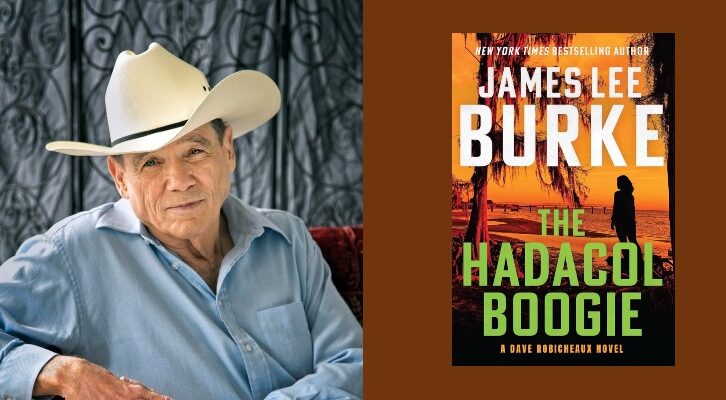

From Café Europa Revisited: How to Survive Post-Communism by Slavenka Drakulic. Used with the permission of Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Slavenka Drakulic.

Slavenka Drakulic

Slavenka Drakulic was born in Croatia in 1949. The author of several works of nonfiction and novels, she has written for The New York Times, The Nation, The New Republic, and numerous publications around the world.