I never agreed to it, but after Carly and I split up, Won appointed himself my life coach. His first directive: I had to swear on everything I wouldn’t call Carly or try to see her; no exceptions, never again, bye girl, have a nice life.

“Remember me and Jesse?” he said.

“The go‑go boy?”

“Camping trip in Joshua Tree. Fantasia’s quarter-life crisis slash birthday weekend.” Won narrowed his eyes at me across the table. “What go‑go boy are you talking about?”

“Where was I?” I said. “Why didn’t I get an invitation?”

“Somewhere with Carly, obviously,” he said. “Being boring,” he added. “Anyway, Jesse should’ve been a one-night stand. Then my stupid ass couldn’t say no to him once we were back in LA.”

The server brought out our food: grilled pork banh mi for me, pho tai with the raw beef on the side for Won. Any time he deigned to travel east of Fairfax, Won insisted on eating at this tiny spot tucked inside Chinatown’s Central Plaza, no more than four tables here, the brown wood clock in the shape of Vietnam on the wall behind the cash register. Usually, I had to drive west to see him.

Won picked up a wedge of lime and squeezed it into his soup bowl, cupping a protective hand around it. “Then he has to tell me about his mom’s dementia, how he’s the only one who takes care of her, blah blah blah—”

“Don’t compare me and Carly to one of your meaningless sexcapades, please.”

“Point is, there’s only one way you get through these things,” Won said. “Cold turkey.” The next step in my regimen, Won instructed, was keeping a journal. “Your first assignment is to write down all of the things you hated about her,” he said.

“There’s nothing,” I replied. “I didn’t want to break up.” I shook my head. “I shouldn’t have gotten so—I lost it. When she said—”

“This is a safe space. You can tell me,” Won said. He leaned toward me and lowered his voice. “She had that white girl funk downstairs, didn’t she.”

I told him he was fired, effective immediately.

“I don’t know how you do all that shit anyway. It looks so scary, all that skin, like it’s about to attack you.” He clawed the air with his hands in loose fists, fingers half-curled, as if defending himself against a predator.

“You’re literally the stupidest person I know,” I said. My mouth was half-full, and a bit of cilantro flew out and landed on the table. “I do mean literally.”

“Okay, okay. Enough joking around.” He reached into the canvas messenger bag that hung from the back of his chair and took out a small blue notebook, bound with a spiral ring. “You have to make a list,” Won said. “When you start feeling all nostalgic, remembering the good times, you’ll have this in your hands as a reality check.”

I touched a finger to the blue elastic band running down the right side of the cover.

“What if I never meet anyone ever again,” I said after a moment.

“Jane,” he said. “We’re twenty-six. What are you talking about?”

“What if Carly was the one?”

“She wasn’t, though.”

“How do you know?” I said. “What if she was my chance—”

“If we’re both still single by the time we turn thirty, let’s get married,” he said. “I’m serious, Jane. Think about the registry—”

“Your mom would be so happy,” I said.

“We should invite Miss King,” he added.

“Obviously she’ll officiate,” I said.

“What about Fiona?” Then he asked if I’d talked to her lately. I mumbled something about the three-hour time difference between us.

“She broke up with Jasper. Did you hear?” he said. “I don’t know how, but they’re still living together.”

“What?” I said. “Why?”

“You should call her,” he said. “She’s going through major—”

“Why doesn’t she call me?” I said. “She has my number.”

Won looked at me for a moment but didn’t press it.

“I’m going through some shit, too.” I stared back at Won, and he knew I wasn’t just talking about the breakup with Carly. Suddenly the joke he made about us getting married wasn’t funny at all. It made me think of my parents. My dad. Then I was angry, and I wanted lunch to end.

I made up an excuse about forgetting an appointment. Won knew I was lying, but I didn’t care.

“Take the notebook,” he said. I swiped it off the table before I cut out, leaving Won by himself.

*

Lately, it seemed anger trembled under the surface of my skin, behind my eyeballs: hot emotion lying in wait for any opportunity to erupt. It was what happened with Carly, too. Without thinking, I’d slapped her. Said things I regret now. Won was right. Cold-ass, rock-hard, freezer-burned turkey was the way it had to be. Not like I had a choice, anyway. She wasn’t returning my calls or emails.

At home that afternoon, I cracked the notebook open. I wrote today’s date at the top of the first page. Stared at the lined sheet for a while. I felt silly, transported to the oily-faced, gangly teenage girl writing at her desk, transcribing the daily accounts of injuries she suffered, slights perceived large and small, the general and vast unfairness of everything.

Last time I kept a diary I was still living at home. I stopped writing in it after Mah began snooping in my room. Though I’d kept it hidden inside a shoe box under my bed, Mah managed to dig it up; that was how she found out about me and Ping, my piano teacher. Baba had moved to Taipei, then to Shanghai. In those years it felt as if Mah and I were constantly tearing at each other’s throats, never a moment’s peace between us. We’d never been close, my mother and me; I was my father’s child. Without Baba’s protection—Mah had always accused him of coddling me—I was left to fend for myself, her paranoia fueled by the hearsay culture of suburban Taiwanese mothers who circulated alarmist emails on, for example, the resurgence of the 1970s party drug called Ecstasy among American teens; how pedophiles insinuated themselves into AOL chat rooms; what to do if you’ve been kidnapped and locked inside the trunk of a Toyota Camry.

Mah confronted me, bending my diary open to the pages where I’d sketched crude illustrations of Ping and me wrapped around each other in various configurations, hands touching, mouths kissing, tongues licking. It must’ve been obvious who I was drawing, from the tattoos and enormous dangling breasts, the grand piano off to the side and floating music notes everywhere. Ping wasn’t my piano teacher anymore when Mah found my diary, but we’d had something when I was a senior in high school. That was how I came out to Mah—I was nineteen and working four days a week at the optometrist’s office on Alondra, just farting around—and when I knew I had to move out of her house.

Under orders from Won, a new notebook. I felt strange as I began to write.

1. Jealousy issues . . .

Carly hated it that I’d been with guys before her. Men were the enemy, even the queer ones. I didn’t take her seriously, but she often ranted that eventually society would evolve to a point where men became obsolete.

“What about babies?” I asked her once.

“Cloning,” she replied.

“What about straight women? Won’t they be lonely?”

Carly thought for a moment. She said, “Heterosexuality is a performance. Once the stage is removed, women will be liberated, and—”

I kissed her to make her stop talking. She knew this trick but didn’t mind.

Over and over, she pressed me for details surrounding my last boyfriend. I didn’t want to talk about him, but she kept needling me. How’d you meet, why’d you break up, how often did you have sex, and the big one: Did you love him. Did you really love him? How much? Why him?

“No, baby,” I said. “I thought I knew all about what love was, but I had no idea,” I added. “Until now, with you.” Sometimes she accepted this answer with a smile. Most of the time, she didn’t buy it.

My past with men became the source of countless fights. Carly believed the more we talked about it, the closer we’d get to the truth. She thought if she could understand it, she might cure me, my attraction to men merely a bad habit to correct, as if I were one of the dogs she worked with at the obedience school.

I wondered if the reason she hated men was as simple as tracing back what Carly’s dad did to her mom. Carly was four when she died. Her dad shot her with a handgun. Carly’s grandparents took her younger brother, but they didn’t want to raise another girl who would just end up like her mom, Carly said, so she passed through foster families and group homes until she emancipated at seventeen. She never saw her brother, those grandparents, again.

“I don’t think about them,” she claimed. “I stopped existing to them, so they don’t exist to me.”

When I asked if her dad was in jail, Carly had nodded her head grimly. After a minute, she said if he ever got parole, she would find him and kill him herself. She’d make him suffer. Feed his limbs to her dogs. Carly had a beautiful German shepherd named Xena and a golden retriever mix with corgi legs called Gabrielle. The muddy greens of her irises were suddenly clear, bright blue.

She asked about my father, but I didn’t tell her the whole truth.

“He passed away a few years ago,” I said.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “At least you still have your mom.”

I didn’t tell Carly he took his own life. He was alone. Without family. My fault, because I’d outed him to Mah. He’d trusted me, his only child. My baby daughter, he used to call me. I let him down.

I didn’t tell her I hadn’t cried once, not since he died.

I just nodded, then changed the subject.

Carly met Won one time, when she and I first started dating last summer. The three of us got together for happy hour at the Abbey. Won complimented the blue in Carly’s hair—Manic Panic, she’d replied, patting her crown self-consciously—and then he asked for her advice about Pepper, the Pomeranian he’d recently adopted. Maybe she felt defensive because I’d told her Won cuts hair at a celebrity salon in Beverly Hills; instead of answering, she cracked a joke about Asians eating dog meat. Won laughed without missing a beat, and the conversation moved on before I had a chance to react. When I confronted Carly later that night, she’d started bawling. She kept insisting she hadn’t meant it “like that.” Like what, I didn’t know. Anyway, I forgave her; it was a mistake. A dumb joke.

Something changed, though. A shift between us, as if before then, I hadn’t realized she was—really, truly—a white girl. I just didn’t think of her that way. She was Carly. My girlfriend. I never talked to Won about it after. There wasn’t ever a good time to bring it up.

__________________________________

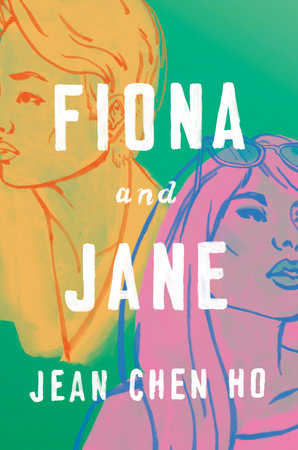

Excerpted from “Cold Turkey” from Fiona and Jane by Jean Chen Ho. Used with permission of Viking. Copyright © Jean Chen Ho.