Clint Smith on Protest, Art, and Protest-Art

Poets on Their Craft and Writing Lives

For the first installment in a monthly series of interviews with contemporary poets, Peter Mishler corresponded with poet Clint Smith. Clint Smith is a doctoral candidate at Harvard University and has received fellowships from Cave Canem, the Callaloo Creative Writing Workshop, and the National Science Foundation. He is a 2014 National Poetry Slam champion and was a speaker at the 2015 TED Conference. His writing has been published in The New Yorker, American Poetry Review, The Guardian, Boston Review, Harvard Educational Review and elsewhere. He is the author of Counting Descent (2016) and was born and raised in New Orleans.

Peter Mishler: Let’s begin with the striking epigraph you chose for your first volume of poetry Counting Descent. It is a quote from Ralph Ellison: “I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest.” Can you talk about your decision to begin with this epigraph?

Clint Smith: Foremost, Ellison is a literary hero of mine. My work is, quite literally, only possible because of his. I taught high school English for a few years in Maryland before beginning my doctoral work, and one of the best moments of my life as an educator was reading Invisible Man with my seniors. It was so fascinating to watch the different ways they responded to the notion of what it means to be considered “invisible.” For example, I taught a large number of undocumented students, so putting their ideas of invisibility in conversation with that of my black students provided some of the most thoughtful and robust discussion I’ve ever been a part of.

But back to the epigraph itself, “I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest.” It’s from a 1955 interview with Ellison in The Paris Review. The larger context of the quote is as follows:

Now, mind, I recognize no dichotomy between art and protest. Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of 19th-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself. If social protest is antithetical to art, what then shall we make of Goya, Dickens, and Twain?

So I’m thinking of this in two ways: First, Ellison is clearly seeking to disabuse us of this notion that “protest literature” is something that is limited to black artists and that our very conception of what even constitutes as “protest” deserves to be dissected and reconceptualized. Art, I think, is inherently a protest of some sort. The role of the writer is to operate in the space of the imaginative, and thus it demands a rejection of the world as it is and movement toward what it might otherwise be.

Secondly, I’m interested in expanding our notion of what does or does not constitute a political act, and the false choice often presented that a writer must choose between creating work committed to artistic integrity and work that responds to the social moment or one that is imbued with their political commitments. There are countless examples of writers who have proven this to be categorically false, but somehow people still feel as if they have to choose between the two. Part of why this is the first thing you see in my book is because I want the reader to know I don’t subscribe to such a belief.

Look, we live in a moment in which a man who predicated his campaign on racism, sexism, and xenophobia has been elected President of the United States. If there was ever a moment to reject the idea that artists should separate their politics from their work, now is that moment. If anything, we should be recommitting ourselves to the idea that this is exactly where the role of the artist lies.

PM: In the middle of the collection there’s a pair of poems, “James Baldwin Speaks to the Protest Novel” and “The Protest Novel Responds to James Baldwin”—were these poems meant to resolve questions about the relationship between art and protest?

CS: Certainly. The entire collection is, in many ways, me wrestling with questions I admittedly don’t have the answers to, and possibly never will. As a writer, I have to be ok with that. In my mind, that’s the power of the genre. It doesn’t necessitate that one have the solutions, but simply pushes us to grapple with the questions. Personifying the protest novel is an attempt to think through the relationship between the polemic and the artistic. In what ways is there a tension? In what ways is that tension simply an illusion? Baldwin’s essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel” is something I read over and over again while writing this collection. I would read this essay, one of his first out in the world, and compare it to some of his later work. And while Baldwin largely inveighs against Richard Wright and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novels in “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” something I don’t think we often consider is that he was only 25 when he wrote that. It was 1949.

He would go on to become incredibly involved in the civil rights movement and develop relationships with activists who pushed his thinking politically in ways I don’t think he anticipated. I imagine that Baldwin would have written that essay differently in 1969 than he did in 1949, which is natural. He said as much in his 1971 conversation with Nikki Giovanni. He had another 20 years of life, conversations, and experiences that would shape how he sees the world. Similarly, I imagine that I will look back at the poems in this book 20 years from now and think differently about some of what I’ve written. It’s an inevitable part of being human, I think. My friend, Safia Elhillo, a brilliant poet, once told me that we have to think of each poem as a small time capsule that holds within it the way we thought about the world at that time in our lives. I thought that was such a wonderful framework, and I think it applies not only to our art, but our politics as well.

PM: The volume contains a series of poems in which several speakers—a fire hydrant, a cathedral, the ocean, a window, a cicada—address a black boy. Were these poems born of some necessity?

CS: When Tamir Rice was killed, I began thinking a lot about the pedagogy of black parenting—the conversations the black parents have to have with their children, teaching them to navigate a world that is often taught to fear them. What is colloquially known in black communities as “the talk.” I began thinking about how difficult it must be to reconcile that ever-present tension between ensuring that your child is aware of the realities of how the world perceives them, while at the same time ensuring that they do not begin to believe that they have done anything to deserve that treatment, or that such treatment should be an inevitable facet of their lived experienced.

I wrote a poem “Counterfactual” about what that conversation looked like when it was coming from my father. After that poem, I began to think of what it might be, as an artistic endeavor, to imagine what inanimate/nonhuman objects and things would say to a black child if confronted with this reality. Would they provide warning? Advice? Solace? I wrote maybe a dozen of them, and five of them ended up in the book. Each object has something specific to tell the child as it relates to their own experience with blackness—just as I imagine any parent would. The arc of those poems throughout the book largely matches the overall narrative structure of the manuscript as a whole—which is that it begins wrestling with the cognitive dissonance of seeing people who look like you incessantly killed at the hands of the state, while seeking to remind ourselves that we are not defined by that which seeks to render us obsolete. We are so much more than that.

PM: I imagine that there are poems in Counting Descent that started with less definite paths than the ones we’ve discussed so far. Of these poems that began less definitively, did any of them become poems you would describe as protest? If so, in the context of your work, I’m curious what you see as the relationship between less ‘knowing’ acts of writing and protest.

CS: More often than not, the poem’s purpose, so to speak, does not unearth itself until the piece is almost complete. Some poems, like the series speaking to the unnamed black boy we just discussed, do begin with a specific question, though the direction of those poems is similarly unclear until the work is complete. Which is to say, when I began “what the cicada said to the black boy” I didn’t know what the cicada would say. I was figuring that out as the poem was being written. It’s much like fiction in the sense that the writer is getting to know the characters as they write the story.

Each of those poems was similar in that way. But there are certainly poems, I’d say most of my poems, that don’t begin with any specific purpose or direction or even a question necessarily. Many of my poems begin while I’m reading. I’ll read something in a poem, an essay, a novel—and maybe it’s simply a word or phrase—that I find moving or interesting or surprising. I’ll often write that word or line down, perhaps in my phone or in a notebook and will revisit it later. Many of my poems are born from that point, simply from a place of wonder and curiosity. But I will say that just because the poem doesn’t consciously begin with a specific question or idea doesn’t mean that the idea isn’t there. It’s inside of me. And because it’s inside of me it will manifest itself in the work either way. So in that sense because my politics are an ever-present function of how I engage the world, it seems inevitable, whether implicitly or explicitly, that those ideas would become present in my work.

PM: One of the poems I return to in Counting Descent is “Line/Break,” in which you illustrate a realization about poetic line breaks you had while listening to Dead Prez. What role has listening as a form of reading played in your development as a poet?

CS: I appreciate that you framed it in that way—“listening as a form of reading.” Because that’s what it is. It’s impossible to disentangle the two. I came to writing through the spoken word tradition, and both my writing and my politics have been fundamentally shaped by that community. It’s an interesting thing, because there is this tacit notion that exists in the ecosystem of the writing community where spoken word is positioned lower on the literary hierarchy than that of more “traditional” modes of literature. It’s rarely stated explicitly, but I think is a presumption unconsciously held by many people. The issue is not only laden with race and class-based pathology, but it’s also historically inaccurate. Poetry was born as an oral art form. To suggest anything else is simply not true. So for me, the musicality of the language—the way it sounds when it rolls off your tongue, is as important as what it means to read something on a page. Each experience has its own unique dynamic, but I think it’s important to push back against the idea that one is a more legitimate means of consuming literature than another.

PM: What are you working on now, poetry or otherwise? I’d love to hear.

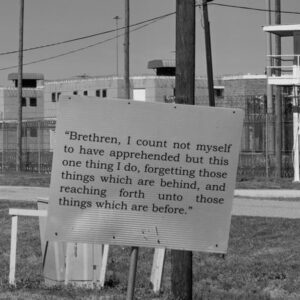

CS: I’m in the beginning stages of my dissertation, which is a series of portraits of people serving life sentences in prisons throughout the country. My academic work largely focuses on the way systems of education and incarceration perpetuate social stratification, and I’m interested in looking at the different facets of those systems through both a policy-oriented and moral lens. I’ve spent the past few years working in prisons in Massachusetts and that work has largely laid the groundwork for this project. I’m looking forward to doing the on-the-ground ethnographic work and to writing an extended non-fiction project, which will be a new challenge.

Peter Mishler

Peter Mishler is the author of two collections of poetry, Fludde (winner of Sarabande Books' Kathryn A. Morton Prize) and Children in Tactical Gear (winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in Spring 2024). His newest poems appear in The Paris Review, American Poetry Review, Poetry London, The Iowa Review, and Granta. He is also the author of a book of meditative reflections for public school educators from Andrews McMeel Publishing.