This story doesn’t have a beginning. I just sat on dining-room chairs with my legs swinging like anyone else; grew possessive over junk plastic, shovelled chicken nuggets down my throat at birthday parties and spent enough time gazing quizzically at the sun to grow yearly, like any uniform sapling. I outgrew clothes and shoes faster than my siblings and felt guilty for it, conscious even then that childhood was a wasteful inconstant medium. At school I excelled for want of a peculiar, comfortable love from my parents, proving perhaps that a plant that’s desperate to be measured grows more. I equated nurture with expectation. And so, I studied ruthlessly, endlessly, until I found myself in my mid-twenties, crowned with an obscene amount of paper, proving my brain had grown beyond capacity, and with an ungodly amount of student debt. (Shit.) When the last certificate plopped through the letterbox onto a pile of takeaway pizza menus, I was disillusioned with the whole thing, and not much more than nonplussed at the triangular crease in the top left-hand corner from the steady grip of the postman, where, I assume, he had positioned his thumb. The poor choice of font did not upset me, nor, indeed, did the quality of the paper, which was not unlike single-ply toilet roll. Back in my bedroom, stood adrift on the only spot of carpet unobscured by dirty laundry, I thought about hanging this thing up nicely in a frame on the wall — that was what proud people did, of course — but I was deterred by the greyish leak creeping down from the ceiling I had yet to ring my landlord about, out of fear of making unscheduled phone calls. The wall was wrong. I could’ve texted the landlord, of course, but the wall would still be wrong. The certificate would have to stay in the envelope and be lost under the bed. A bed that was not even mine. (Shit.) I looked upon what I had created here and saw myself stuck inside a vortex of my own messes. My small room seemed to be visibly clouded by the stink of my body and the stink of my superfluous thinking. After spending two months in my bed, I grabbed the nearest jacket and rushed out onto the street, gasping theatrically for air. The shock of sunlight made my eyes stream with tears. I plugged my earphones in and began walking through this city I had been living in for years but somehow knew nothing about. I did not stop until a man called out to me and I was caught short by the reality of real night-time, when only moments before I’d been transfixed by a great wash of pink over the spire of an old church. I’d been walking for hours, my stomach was gurgling; another day had died right before my eyes. This man who had brought me to my senses cried something not untrue about the state of my body, which I noted down verbatim on my phone, as had become an unorthodox habit of mine. I turned back the way I had come through the wide city streets and reached the door just as the sun rose, crawling into my bed at about 6am. I awoke, damp and groggy, some time after 5pm, only to drink cup of instant coffee after cup of instant coffee, grab my jacket and repeat the whole pointless excursion all over again. I woke, I walked, I lived on deli sandwiches in recyclable paper and I watched each watery sunrise until my lease on the flat ran out some weeks later. My other housemates were long whisked away by beckoning purpose. Alone, I spent a sad afternoon sweeping the carpet in the absence of a vacuum cleaner and depositing bin bags of things I couldn’t fit into my suitcase at various charity shops.With my certificates packed neatly in my bag, I trundled home on the train to my parents’ house, resigning myself to the fact I’d never get my deposit back. I swapped the city I found for the city I came from. There, I spent a month or so nightwalking through my old childhood haunts (the chip shop where I got slapped once, the library where I discovered reading) and faced my parents’ bleary-eyed questions by day, when I’d knock on the front window to be let in at dawn, like some sort of sloping street-cat pushing its luck: Hold me, feed me, I have never known the joy of attention! After about a week of this, my limp, doughy parents tentatively suggested I find myself some employment — You could work nights? — which I ignored. I asked them instead what I could do for them, but they were happy, which was a shame. It surprised me. I found myself for the first time intensely jealous of what cannot have been a particularly exciting life. I was the most educated person in the whole family and I could offer them nothing.

__________________________________

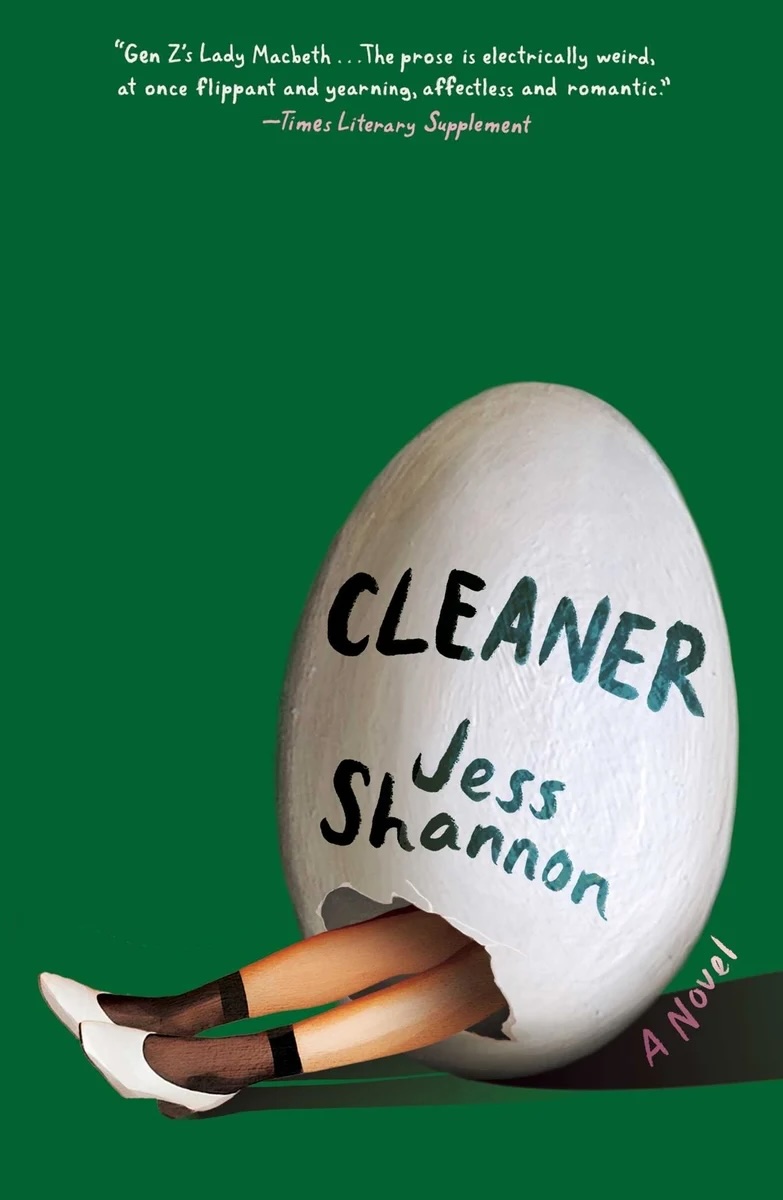

From Cleaner by Jess Shannon. Used with permission of the publisher, Scribner. Copyright © 2026 by Jess Shannon.