After the incident with the power washer, I was determined to get my life together. Grandma sent me a gift card for Christmas that arrived after New Year’s, and instead of trying to sell it, I decided to buy myself some decent clothes. That’s how I met Jacky. She worked at the Jordache$Fitch store near campus, folding sweaters.

When I asked her name she said, “Jacky with a Y,” in that soft drawl that still haunts me.

Together we weaved through the neatly stacked and color-coded shelves and I let her pick out shirts for me. Emboldened by my ability to stay clean for five weeks, I asked her out, hoping she was the kind of good thing that happened when you quit getting high.

“Sure,” she said, “dinner and a movie sounds nice.”

“Grand,” I said. I’d never used that word before.

She lived with her parents on the edge of the nice part of Booth. When I arrived at her place, her sister met me at the front door and looked at me funny. Like, where does this white kid in his ridiculously tight shirt think he’s taking Jacky in that station wagon with no mirrors and “FUCK YOU” keyed into the side?

Jacky’s hair coiled like a bouquet of watch springs and bounced when she skipped down her front steps. That Carolina-blue dress was magic rolling past her knees, like she was on her way to church dressed as Alice on leave from Wonderland. After dinner we watched a movie about a kid who could fly.

Without asking, she lit a joint in the car on the way back to her house. Our fingertips touched when she passed it, and the steering wheel grew slick with my sweat as I took the long way back to her house.

Row houses gave way to farmhouses and barns. Streetlights to moonlight and stars. A spark of disappointment burned in my throat, but the feeling got wrapped up in the cloud of smoke curling in front of Jacky’s dark eyes and sucked into in the winter night. Gone as fast as she could change the music.

“You like country?”

“Old stuff,” I said.

“Me too.”

After a couple hits I waved it off, feeling like the wind might lift me out of the cracked window.

Jacky fingered the hem of her dress.

On the radio a man sang of whiskey and ruin.

Jacky invited me in. Before I could pretend to get nervous about her parents or how much noise the stairs made when we creaked into her basement bedroom, she pinned me against the wall.

“Why?” she asked. Her nose nudged mine, her lips against my cheek.

“Why what?”

“Why are you making me do this?”

The slippery blue material of her dress swirled between us and made sounds like TV static as she kissed the corner of my mouth. Her leg wrapped around my waist at an angle I still can’t comprehend.

*

In August, after dating for almost nine months Jacky and I moved into this great old house on Fredrick. The hardwood floors creaked all night and half the windows had been painted shut, but it was as spacious a place as I’d lived in since childhood. Jacky bought it at auction and paid in cash.

When I finished school, Jacky got me a job in the Jordache$Fitch warehouse as a Blue Jean Vintage Modification Technician. From 9am-8pm, I modified new, un-broken-in, acid-washed denim pants. This modification entailed donning the tight, tapered pants, sprinkling on three ounces of acid wash solution, and lunging.

“Initially it was perfect. Thanks to Jacky’s connection, there was money and glass everywhere. Work went by a lot faster.”

Lunges and squats. Fifty lunges per pair, fifty pairs a day. After this, I’d use a melon-baller and a hammer on each pair to slightly rip and fray the jeans before they got passed on to the Wallet Imprinting Division. I got two free pairs of jeans per quarter (Over $1,000 retail) and just over minimum wage.

Work wore me down. I’d come home at night on wobbly legs, reeking of bleach and crawl into bed next to Jacky. I’d lay there with the light on and watch her chest rise and fall.

*

When Jacky wasn’t selling clothes she moved pounds of weed she got from Tom Canada, a near-mythological figure in Booth. A whack job recluse with his hands in a little bit of everything. Tom was paranoid, but he trusted Jacky, trusted her almost exclusively. This was all well and good until September, when an old friend of Jacky’s moved to Pittsburgh and set up a meth lab outside the city near Trafford, Pennsylvania. The stuff she cooked had a weird blue tint to it, like Jacky’s dress, and this friend sent us pounds of it in the mail. It arrived in old Lego boxes, and we called it Trafford Dynamite, The Ghost of Trafford, Blue Dynamite, Blue Ghost, or some such variation.

Initially it was perfect. Thanks to Jacky’s connection, there was money and glass everywhere. Work went by a lot faster. I broke in 150 pairs of J$F a day. I was a machine. I was promoted to Shift Supervisor.

By Halloween Jacky was supplying most of the tri-state area with meth. Jacky never cut breaks and didn’t front anyone. Her only thing was that she would take trade.

I’d sit in the den, smoking pot, and watch these hollow-eyed shaky kids with their spines all tangled carry music boxes and pocket watches up the front steps. One speed freak antiques dealer furnished our house.

The biggest thing Jacky ever acquired was this kid Justin’s piano. Maybe six weeks before I got thrown in jail, Justin fucked up a deal with these guys down in Tampa that was supposed to make Tom Canada ten grand.

It was a humid summer morning when Justin showed up at our place begging for Jacky to front him a couple pounds of meth so he could sell it and make back the money he’d lost on the Tampa deal, so Tom Canada wouldn’t cut him up into pieces and send them to his mom in the mail. “Don’t ruin my plan,” he told Jacky.

Jacky said, “No breaks.”

“You’re being completely unreasonable,” said Justin. “What do you really want?”

“I told you, the piano,” Jacky said, and that was it. She charged him street value, less the cost of the piano, for three pounds of meth.

Jacky put up the money for the movers and the truck and everything. Justin came back in the afternoon. Justin paid Jacky and cut himself out a taste in the office while we waited for the truck to arrive.

They had to pulley the thing up to the balcony and through the double doors that opened into the master bedroom on the second floor. The room was already crowded with electronics and designer clothes and a collection of lamps we didn’t have space for.

One of the movers had a nose ring and a bad tattoo that looked like someone did it with a knife and fork. “Can’t get it down the stairs,” he said. “It’s staying here.”

“There’s a room next door,” Jacky said.

“Door’s too small,” he said, and mussed his greasy haircut.

Jacky stood and stared at the bed. “Through the wall.”

“What?”

“The wall. Go through it.”

I helped sledgehammer through the plaster and drywall, and after an hour we rolled the baby grand into our new sitting room.

Jacky lit a cigarette and sat on the piano bench. “It’s a shame,” she said. “I don’t even play.”

One time Jacky took a complete set of 1989 Upper Deck baseball cards off a kid for a twenty-bag. She gave me the Ken Griffey Jr. rookie card, the crown jewel. “Because I know he’s your favorite,” she said.

By the time Christmas came back around our house was filled with other people’s memories. But I didn’t mind. They were better than most of my own.

![]()

On May 20, Ben Gwin will be reading at City of Asylum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as part of the Free Association Reading Series.

__________________________________

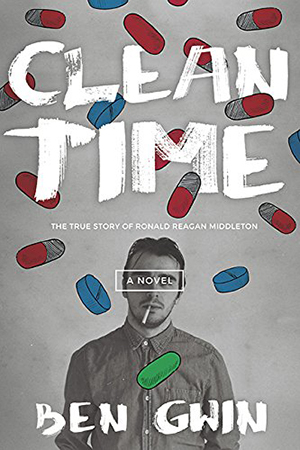

From Clean Time. Used with permission of Burrow Press. Copyright © 2018 by Ben Gwin.