Claire Dederer on Doris Lessing and the Divided Mother

Finding Freedom in, and From, Motherhood

The hardest-hearted woman isn’t a murderer or rapist—she’s a leaver of children.

In 1949, Doris Lessing left behind two children from her first marriage when she moved to London from then-Rhodesia. Lessing brought along her third child, Peter, as well as a suitcase containing the manuscript for The Grass Is Singing. Once she got to London, the novel was published (or re-published—it had previously been published in Rhodesia) to great acclaim, and Lessing went on to become one of the few female literary lions this planet has ever hosted, however grudgingly. Eventually of course she won the Nobel.

As for Peter, he lived with her until they both died, within a few weeks of each other, in 2013. Even abandoning mothers somehow end up lumbered with children.

A little more than a decade after she arrived in London, Lessing published her most famous novel, The Golden Notebook, which deals with the problem of how to live as a free person. Among other questions, the book examines and illuminates the question of how a female artist is supposed to live in a society that doesn’t really want her to exist and make work.

While The Golden Notebook is shot through with the desire for human liberty—its real subject is the failure of communism to solve human relationships—the problems of motherhood haunt its pages, a kind of boggy murk that sucks and burbles at the ankles of its freedom-seeking females.

The novel is radically experimental in shape, even read from today’s vantage—it’s comprised of several different books, or rather notebooks, as they are called here, identified by color. Woven throughout all this is a more conventional novel-within-a-novel titled “Free Women,” about an alter-ego-like novelist named Anna Wulf. I hesitate to call “Free Women” autobiographical, but only because it seems like Doris Lessing wouldn’t approve of calling things autobiographical, and Doris Lessing scares the bejeezus out of me, even from the grave.

Nonetheless, it is irresistible to imagine the novel about Anna Wulf as the story of Doris Lessing’s own experience of seeking freedom—from her children, from her old life in Africa, from forces that would stop her from making art. The selection of just one child makes her flight even more unthinkable—if all the children were abandoned, the two left behind might have justified it to themselves. But not-abandoning just one child sends such a strong message to the others; you were not good enough.

When I first read The Golden Notebook, I was in fact a free woman. I was 21 years old, a college dropout living in a little house on the wild coast of New South Wales. I had ended up in the faraway antipodes for reasons I didn’t really understand. Okay, I followed a boy there—a relationship that didn’t work out. Now I had a tiny room to myself and I worked in a warehouse and aside from that I spent my time drinking beer, going to punk rock shows, hopping trains, and reading. Reading was my vocation, if a vocation is what you do when you are left entirely to your own devices.

This is what Lessing calls luck—the ability to fight the housewife’s disease of resentment, to know it’s an impersonal poison.

I liked massive books then—like many free people, I found myself confronted with a string of empty days, and the longer a book kept me occupied, the better. The Golden Notebook was picked at least in part for its size, after a long bout with Anna Karenina. The problems faced by Anna Wulf were unknown to me; these were problems that had to do with commitments—to a child, to a politics, to a future. I was committed only to the pleasure of the day. But I chimed to the idea of freedom, and I could feel I was doing it wrong. Freedom, I intuited, ought to have higher stakes, and much much greater rewards than all the time in the world to read fat novels and steal a ride on a train to a rock show in the sticks somewhere.

Even if its concerns were not yet my own, I loved the book. It ate my hours. And I found Anna Wulf, Lessing’s alter ego, irresistible. I loved the honesty of one passage in particular, when Anna Wulf wakes at the crack of London dawn with a lover in her bed and a small daughter in the room next door. She is trying to be a free woman and it’s not easy and the stakes are perhaps altogether too high.

It must be about six o’clock. My knees are tense. I realize that what I used to refer to, to Mother Sugar [her nickname for her analyst], as ‘the housewife’s disease’ has taken hold of me. The tension in me, so that peace has already gone away from me, is because the current has been switched on: I must-dress-Janet-get-her-breakfast-send-her-off-to-school-get-Michael’s-breakfast-don’t-forget-I’m-out-of-tea-etc.-etc. With this useless but apparently unavoidable tension resentment is also switched on. Resentment against what? An unfairness. That I should have to spend so much of my time worrying over details ..

It’s not just the doing of the chores that eats at Anna Wulf, it’s the worrying and the thinking and the remembering—what we might now call the emotional labor. She is tense with the fact that she is alone in being the woman/mother self. She goes on, thinking about her analysis:

Long ago, in the course of the sessions with Mother Sugar, I learned that the resentment, the anger, is impersonal. It is the disease of women in our time. I can see it in women’s faces, their voices, every day, or in the letters that come to the office. The woman’s emotion: resentment against injustice, an impersonal poison. The unlucky ones, who do not know it is impersonal, turn it against their men. The lucky ones like me—fight it.

All that was still ahead of me when I first read this passage. I was a free girl, in some ways closer to Anna Wulf’s tiny daughter Janet than to Wulf herself. Freedom came naturally to me. I devoured The Golden Notebook on the train, in my monk-like little room, down at the pub while I waited for a lover to arrive, with his accent that was just normal life to him and a kind of wild excitement to me. In those days I gobbled the parts of The Golden Notebook that were about communism and love and found myself a little frightened of the motherhood passages. Surely that would never be me.

Two decades passed.

When I next came to the book, I was a mother of two. A homeowner, a cook, a wife, a gardener, a teacher, a driver, a cleaning lady. I found myself yearning for enough freedom, just enough freedom, to get my writing done. This time around, I found the passage, to use the parlance of our own day, intensely relatable: “The resentment, the anger, is impersonal. It is the disease of women in our time. … The unlucky ones, who do not know it is impersonal, turn it against their men.”

These latter days I feared I might be one of Lessing’s unlucky ones, taking it personally over and over, finding in my husband’s inability to overcome the privileges of millennia and do the fucking dishes evidence of his lack of love and respect for me.

This is what Lessing calls luck—the ability to fight the housewife’s disease of resentment, to know it’s an impersonal poison. This poison is well known to any woman who’s ever regarded the landscape between the making of dinner and the singing-to-sleep as a vast wasteland, on a par with the bleaker landscapes from Planet of the Apes. And I don’t know any mother who hasn’t at least once felt that way, though they meet the moment with varying levels of despair or sangfroid, depending on their situation, their income, their level of desperation. Depending on how much their husband does the dishes, how accepting their natures are, how radical their politics are. How afraid they are.

But why couldn’t I accept that the situation might be impersonal? Might, in other words, not be my own fault, not be my own individual problem? Why couldn’t I be one of Lessing’s lucky ones?

When my daughter was three years old, I used to pay myself to play with her.

It’s a strange loop. Lessing is giving voice, through Anna Wulf, to the pressures that make a woman feel it is difficult to get her work done. (Her real work? At any rate, her art.) The pressures that might lead a woman to, oh, say, leave two children behind on a whole other continent.

Anna/Doris’s ambivalence about motherhood is given full throat in what would become one of the most famous passages from The Golden Notebook, a passage that is a perfect tiny bijou portrait of maternal apathy and dissociation:

Janet looked up from the floor and said, ‘Come and play, mummy.’ I couldn’t move. I forced myself up out of the chair after a while and sat on the floor beside the little girl. I looked at her and thought: That’s my child, my flesh and blood. But I couldn’t feel it. She said again: ‘Play, mummy.’ I moved wooden bricks for a house, but like a machine. Making myself perform every movement. I could see myself sitting on the floor, the picture of a ‘young mother playing with her little girl.’ Like a film shot, or a photograph.

This is the job of any good novel, or maybe even piece of writing: to reveal felt and lived experience, rather than what you think you ought to feel. The consciousness-raising sessions of second-wave feminism were built on exactly this idea. What if you said how you really felt? Would that be a revolutionary action? I suppose it depends in part on who does the saying. Lessing is doing important work in this passage. For women, laboring in domesticity, otherwise known as anonymity, it’s all the more important to get at this truth of felt experience.

This sense of being an imposter, this quiet chafing against the role of mother—I lived it. For years and years, I lived this fear that I was not, am not a good enough mother because I cannot inhabit the role with my entire being, cannot cast out the artist self, or maybe the true self, a self that is not entirely good. This is why, when my daughter was three years old, I used to pay myself to play with her. I chivvied myself into behaving like a good mother, but inside, sometimes, I felt like Anna Wulf: a machine, a film shot, a photograph, a simulacrum, a bifurcation, an other, a divided self.

The divided self is a common story for female artists. Lessing’s story is echoed in the lives of other writers, from Jean Rhys to Alice Walker. And yet. Even if one stays home, even if one has luck, has money, has help, children and writing often seem stubbornly orthogonal, two forces constantly pitted against one another.

When I began to think of female monsters, Anne Sexton was one of the first names to come up. She was the harpy-mother, the screeching taloned swooping poetess, the housewife artiste who cherished her neuroses more than her children; the mother whose offspring were sacrificed at the altar of her terrible creativity.

Sexton is nowadays arguably as famous for her daughter Linda Gray Sexton’s incendiary memoir Searching for Mercy Street as she is for her poems, although she was once one of the most famous poets in America. Though is there even really such a thing as poet fame? It’s like trying to measure the speed of a butterfly’s fastball.

After Sexton’s death, Linda Gray Sexton found tapes of her mother’s therapy sessions. The transcripts reveal Sexton as a kind of nuclear version of Anna Wulf: her ambivalence has superheated. She is the dissatisfied mother/artist, turned up to 11. [CE183] For instance, this passage:

I drink and drink as a way of hitting myself.

I started to spank Linda and Joan hit me in the face.

Three weeks ago I took matches and went into Linda’s room.

Writing is as important as my children.

I hate Linda and slap her in the face.

This writing is so alarmingly good that it’s easy to forget it’s not writing at all, it’s actually tormented talking. The passage is shot through with a kind of brittle, compulsive truth-telling. It will be hard to forget the image of drinking as a way of hitting myself. And obviously “Three weeks ago I took matches and went into Linda’s room” is a great opening line to a poem or story or an opera or pretty much anything.

But where you really feel the transgression is in the line “Writing is as important as my children,” buried in the list of terrible utterances. Is it a truth? Or is Sexton playing at saying the unsayable, as one sometimes does in therapy?

I read the line and immediately it felt like a gauntlet thrown down. Did I believe my writing was as important as my children? I didn’t think so, but I thought perhaps it was important to try thinking it, try saying it, to roll the words like olives in my mouth:

Writing is as important as my children. Just thinking it made me want to throw up.

When I think of Doris Lessing, I think of her abandoned children. Does that mean her biography has disrupted her work for me? Or—scary thought—enhanced it?

__________________________________

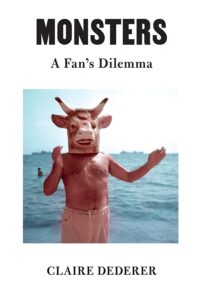

From Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. Used with the permission of the publisher, Knopf. Copyright © 2023 by Claire Dederer.

Claire Dederer

Claire Dederer is the bestselling author of Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma; Love and Trouble; and Poser. Monsters was a New York Times Notable book and was named a best book of 2023 by the New Yorker, Fresh Air, the Washington Post, Esquire, and many others. Dederer has written for The New York Times, The Paris Review, The Nation, The Atlantic, Vogue, Slate, and New York magazine. She is the recipient of a Lannan Foundation residency, the Los Angeles Times Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiographical Prose, and the 2025 Chowdhury Prize in Literature.