City of Ash: Photographing New York City on the Morning of 9/11

Photographer Rachel Cobb on Documenting a Disaster While It Is Still Unfolding

I thumbed a ride downtown and hurried toward the scene. It was a brilliant September morning, as has often been noted, but as I approached the fallen buildings, smoke turned the sky dark gray and obscured the sun. White paper fluttered through the smoke. Sometimes the air would clear, the sun would break through, catching the ash in the air which would refract back into my camera lens. My photos from that day have a strange look to them that a printer once complained about to me, implying I didn’t know how to expose a frame.

Police kept pushing me back, yelling, threatening. I don’t remember it being hard to breathe, but I vividly recall how hard it was to change my film. There was too much debris in the air. I ducked into a bank. It was the corner of Broadway and Vesey. The lobby was all glass and brass-covered metal. Firemen were taking a break in the clean inside air. It was then that the news came in. Their comrades who’d gone up the building, who’d continued to go up, were all gone. Several hundred. I had trouble understanding. My mind couldn’t accept the numbers, but for them, always aware of the danger of their job, it was clear. They shouldn’t have had to share that moment with me. It was theirs; it was private. I loaded the roll, slammed the camera back shut and headed out, dodging the cops stationed on the corner.

All the while I kept thinking “this changes everything, the world will never be the same.”

Outside someone was distributing face masks. Somebody shoved a few in my hands. I tried one on, but it didn’t help. I ran into a colleague. I gave him a mask. To this day, every time I see him, he reminds me of that moment.

All the while I kept thinking “this changes everything, the world will never be the same.” When you’re in the middle of a news story, you can easily not know the bigger picture that people watching tv or listening to radio are aware of. I caught snatches of conversation. “They got Chicago.” “They got London.” I took refuge in a bus that had presumably been brought to ferry the injured. The radio was on. That is where I first heard confirmed reports about the other planes in Pennsylvania and Washington, DC. I sat there for a few minutes wondering when the injured might arrive. Then I remembered the firemen.

As I recall, the lower Manhattan subways were closed. That must have been why I walked a couple of miles north. As I moved further away from the devastation, the streets were less covered in debris and ash, there were fewer crushed vehicles and broken windows. Bright billboard advertisements looked strangely out of place. I had done a modest amount of reporting from war zones and a lot from messed up places. Usually the journey back to New York City took a day or two, the chaos receding first by a long car or bus ride, then by a flight. The streets and fields below suddenly ordered. The mind had time to adjust. This time the war zone was 40 blocks away.

That night, when I dropped my film at the Time-Life lab in midtown—in those days still at Rockefeller Center—the guys looked at me and said: “We’ve got a shower in the back, if you want.” I didn’t realize that I was covered in ash.

*

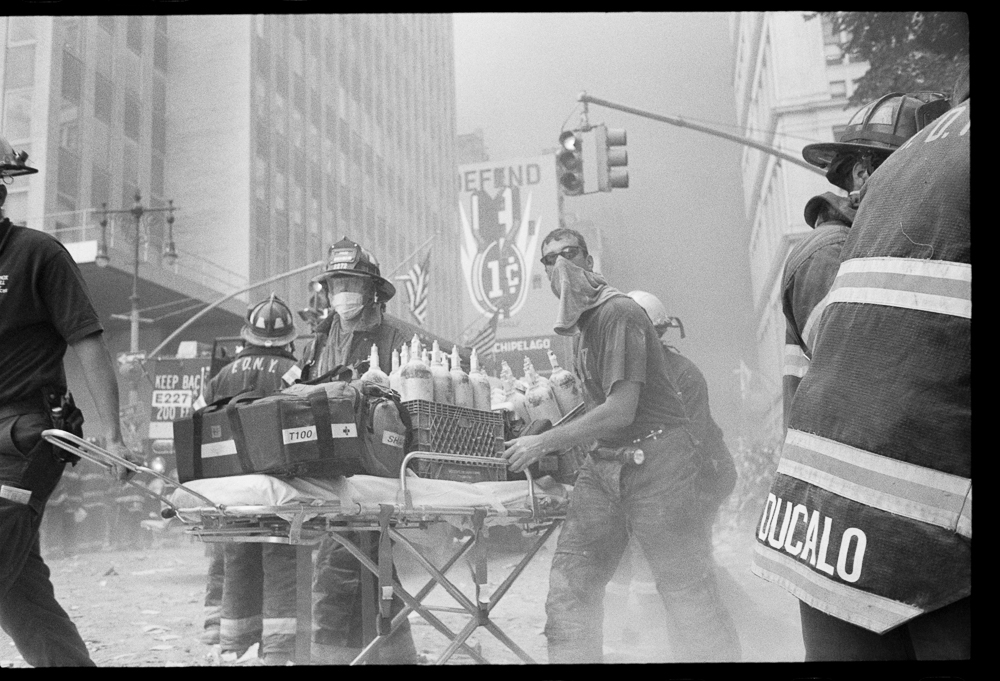

Fire fighters rush oxygen tanks and medical supplies to the scene on a gurney.

*

Firemen come away from the collapsed World Trade Center after the attacks.

*

Firemen use subway maps to plan.

*

A volunteer brings snow shovels.

*

Photograph among the ashes.

*

Exhausted fire fighter, Saint Paul’s chapel.

*

In Tribeca, just north of the burning World Trade Center wreckage, a family hurries away, covering their mouths from the smoke.

*

Firemen are dispatched to the site illuminated by klieg lights.

*

A gurney for the wounded who never came.

*

A mother donates coats to the relief effort at Saint Vincent’s hospital.

*

A man grimaces looking at a bus stop covered with posters of the missing.

*

When the reality set in that the missing would not be found, the signs became memorials.

*

Funeral for Father Mychal Judge, chaplain to the New York City Fire Department, killed while performing his duties at the World Trade Center.

*

Ruins of the towers.

*

Day after day, people come to look at the ruins.

*

Henry Stanley visits the ruins and looks on in anger and disbelief.

*

After taking a look at the ruins.

*

By September 13th, the National Guard is widely deployed in New York City.

*

During a vigil for victims of the attacks, a Lincoln Center guard lowers the American flag.

*

Even in December, the fires were still burning in the wreckage of the World Trade Center known as “The Pit.”

____________________________

To see more of Rachel Cobb’s work, head over to Instagram.

Rachel Cobb

Rachel Cobb is a photographer who lives in New York City. She has worked for numerous publications including The New York Times, Time magazine and Rolling Stone magazine. Her award-winning book Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence was published by Damiani in 2018. You can find her on the web at @rachelcobbphoto.