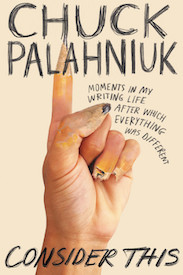

Chuck Palahniuk on the Importance of Not Boring

Your Reader

The Author of Fight Club Finds Parallels Between Film and Prose

You’ve been there. You’re having dinner with friends, talking up a storm. After a laugh or a sigh, the conversation falls to silence. You’ve exhausted a topic. The silence feels awkward, and no one puts forward a new topic. How do you tolerate that moment of nothing?

In my childhood, people filled that pause by saying, “It must be seven minutes past the hour.” Superstition held that Abraham Lincoln and Jesus Christ had both died at seven minutes past the hour, so humanity would always also fall silent to honor them at that moment. I’m told that Jewish people fill that silence by saying, “A Jewish baby has been born.” My point is that people have always recognized those uncomfortable moments of nothing. Their ways to bridge that silence arise from their shared history.

We need . . . something to hide the seam between topics. A bland sorbet. Films can cut or dissolve or fade to. Comics simply move from panel to panel. But in prose, how do you resolve one aspect of the story and begin the next?

Of course you can move along in one unbroken moment-to-moment description, but that’s so slow. Maybe too slow for the modern audience. And while people will argue that today’s audience has been dumbed down by music videos and whatnot, I’d argue that today’s audience is the most sophisticated that’s ever existed. We’ve been exposed to more stories and more forms of storytelling than any people in history.

So we expect prose to move as quickly and intuitively as film. And to do this, let’s consider how people do it in conversation. They “whatever.” They say, “Let’s agree to disagree.” Or, “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you like the play?”

My friend Ina quotes The Simpsons with the non sequitur, “Daffodils grow in my yard.”

Whatever the saying, it acknowledges an impasse and creates the permission to introduce a new idea.

In my novel Invisible Monsters, it’s the two sentences, “Sorry, Mom. Sorry, God.” In the original short story that grew to become Fight Club, it’s the repetition of the rules.

The goal is to create a chorus appropriate to the character. In a documentary about Andy Warhol, he said that the motto of his life had become “So what?” No matter what happened, good or bad, he could dismiss the event by thinking, So what? For Scarlett O’Hara it was, “I’ll think about that tomorrow.” In that way, a chorus is also a coping mechanism. It hides the seams in narrative the way a strip of molding hides the junction where walls and floor meet. And it allows a person to think beyond each new drama, thus moving the story forward and allowing unresolved issues to pile up and increase tension.

If done well, it also calls up a past event. Our superstition about “seven minutes past the hour” served to reinforce our mutual identity as Christians and Americans. I’d wager that most cultures have a similar device that arises from their history.

These sayings reinforce our group identity. They reinforce our chosen method for coping with impasse. And they can carry the reader between shifts in prose.

An aside: As a kid during the dawn of television commercials for Tampax and feminine hygiene sprays I loved how one of those ads would spur my parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and adult cousins into lively conversation. We’d sit like dumb rocks through Bonanza, but the moment a douche commercial sprang up on the screen, everyone yakked like magpies to distract each other. This is a bit off-topic, but a similar phenomenon.

Among my friends in college, our coded insider talk was constant. During meals if someone had a bit of food on his chin, someone else would touch that spot on her own face and say, “You have a gazelle out of the park.” On road trips, if someone needed to find a toilet, he’d say, “I have a turtle’s head poking out.”

My point is that these sayings reinforce our group identity. They reinforce our chosen method for coping with impasse. And they can carry the reader between shifts in prose just as easily as jump cuts carry a viewer through a film.

If you were my student I’d tell you to make a list of such placeholders. Find them in your own life. And find them in other languages, and among people in other cultures.

Use them in your fiction. Cut fiction like film.

*

The most basic way to imply time passing is to announce the time. Then depict some activities. Then give the time. Boring stuff. Another way is to list the activities, giving lots of details, task after task, and to suddenly arrive at the streetlights blinking on or a chorus of mothers calling their kids to dinner. And these methods are fine, if you want to risk losing your reader’s interest. Besides, in Minimalist writing abstract measurements such as two o’clock or midnight are frowned upon for reasons we’ll discuss in the section on Establishing Your Authority.

As a better option, consider the montage. Think of a chapter or passage that ticks off the cities of a road trip, giving a quirky detail about what happened in each. It’s just city, city, city, like the compressed European tour montage near the end of Bret Ellis’s Rules of Attraction. Or picture the little cartoon airplane we see navigate the globe from city to city in old movies, quickly delivering us to Istanbul.

In Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York, the montage is a list of the daily menus in an asylum. Monday we eat this. Tuesday, this. Wednesday, this. In the Bob Fosse film All That Jazz it’s the repeated, every-morning quick-cut sequence of the main character brushing his teeth and taking Benzedrine and telling the bathroom mirror, “It’s showtime!” Whether you depict cities or meals or boyfriends, keep them brief and compress them together. When the montage ends we’ll arrive at an actual scene, but with the sense that considerable time has passed.

If you were my student I’d hem and haw but eventually tell you about using the space break to imply time passing.

Another method to imply time passing is intercutting. End one scene and jump to a flashback, alternating between the past and present. That way, when you jump back to the present you won’t have to arrive at the moment you left off. Each jump allows you to fudge time, implying it’s passed.

Or you can intercut between characters. Think of the various plot threads in John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil or in Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City. As each character meets an obstacle, we jump to a different character. It’s maddening if the reader is invested in just one character, but every jump moves us forward in time.

Or cut between big voice and little voice. With this in mind, think of the varied chapters in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. At times we’re with the Joad family as little-voice narration depicts them on their journey. Other times we’re reading a big-voice passage that looks down in a generalized way to comment about the drought, the stream of displaced migrants, or the wary landowners and lawmen in California. Then we cut back to the Joads farther along their route. Then we cut to a big-voice chapter about the weather and the rising floods. Then we cut back to the family.

If you were my student I’d hem and haw but eventually tell you about using the space break to imply time passing. You just end a scene or passage and allow a wide margin of blank page before you begin a new scene. I’m told that early pulp novels used no chapter breaks. They just used smaller space breaks so publishers could avoid the blank page or page and a half that might be wasted between chapters. This saved a few pages of newsprint in each book, and that helped the profit margin.

In my novel Beautiful You I used space breaks instead of chapter breaks because I wanted to mimic the appearance of mass-market pornographic paperback books. In 1984 Orwell mentions pornographic novels written by machine for the proletariat—that and the raunchy, absurd genre of “Slash” fiction inspired me to mimic their use of white space for transitions.

The writer Monica Drake tells of studying under Joy Williams in the MFA program at the University of Arizona. Williams scanned a story submitted to the workshop and sighed, “Ah, white space . . . the writer’s false friend.”

Perhaps it’s because a space break—without cutting to something different, a different time period or character or voice—can allow the writer to revisit the same elements without creating tension. For example, if we use space breaks to cut between the events in Robert’s day, the story could get monotonous. But if we cut back and forth between Robert and Cynthia and some ancestor of them both in Renaissance Venice, the reader gets time away from each element and can better appreciate it and worry about outcomes.

So if you were my student I’d allow you to start out using space breaks to imply the passage of time. But don’t get comfortable. Those training wheels are going to come off sooner rather than later.

———————————————

Excerpted from Consider This by Chuck Palahniuk. Copyright © 2020 by Chuck Palahniuk. Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Chuck Palahniuk

Chuck Palahniuk is the author of Fight Club, Choke, and many other novels. His latest, Legacy, is an adult coloring book available from Dark Horse.