Chronicle of a Hard-Won Defeat: Steve Prefontaine's Olympic Debut

Brendan O’Meara on the Star Runner's Performance at the 1972 Summer Games

On the afternoon of Sunday, September 10, 1972, when the 5,000 meters was set to go, it was muggy in Munich. Given the hot conditions in the stadium, the runners would not find any relief. All thirteen runners took their place at the top of the backstretch, the starting line for the 5,000 meters. American track star Steve Prefontaine, the youngest in the race by two years, stood beside Belgian runner Emiel Puttemans toward the outside of the field, bib No. 1005. He kicked his feet, pulled his trunks up, then shuffled and kicked his feet. He was fidgety and visually nervous, but so was everyone else. Ralph Mann, who had won the silver medal in the 400-meter hurdles and would become a close friend of Steve’s, had noticed that Steve looked rather gaunt, sunken. Stewart would start on the far outside, Virén and Gammoudi, the defending 5,000-meter champion, toward the middle. Gammoudi toppled over Virén in the 10,000-meter final and did not finish, so he entered the 5,000 meters far fresher than he otherwise would have had he finished the 10,000.

The stadium was packed, and flags waved. There were yellow shirts freckling the crowd, many of which read “Go Pre.” Steve’s girlfriend sat in the stands, along with Steve’s parents, who had spent the previous weeks visiting some of Elfriede’s family from her native Germany.

At last, it was time. Steve had summoned the strength through qualifying and here he was, at the starting line, and…he lost his motivation to run. After all the years, all the work…it wasn’t there. Running seemed so pointless, what with the death of fellow athletes. When they were called to the starting line, he thought to himself, God, it’s almost over. This whole thing is almost over. The gun was about to pop off for the biggest race of his life, and he was absent in mind. He wasn’t himself. This isn’t me about to run this race. In his own words, the tragedy had stripped him of his desire and, worst of all, his identity. He was a ghost of himself, and if he was going to win—or even medal—there were factors at play as strong or stronger than the twelve other men in the field.

Anyone who knew Steve as a runner, knew his style, could sense his growing impatience. The race wasn’t supposed to be this slow for this long.

Yet here he was, looking stricken, his ribs, even his sternum, visible through his skin. Alas, he shook his legs out one more time, approached the line, and took his mark. The starter raised his pistol into the air. A calm settled over the field and—pop—they were off.

Ian McCafferty and Ian Stewart cleared the field to establish better position as the field bent around the first turn. Steve settled in mid-pack, amidst a flurry of traffic, where someone stepped on his foot and tore his shoe. Just a shoe, not his foot. David Bedford of Great Britain was predicted to set the pace—a suicidal one, perhaps—but he loped toward the back of the field early on. Bedford had set a blistering sub-60 first lap in the 10,000 final a few days before and ultimately finished sixth. What he was waiting for in the 5,000 was anyone’s guess. When it came to pushing the pace, “he must be the first one to make a move,” David Coleman, the TV race announcer, said in his brilliant British accent. “This is very slow, in fact, they’ve jogged half a lap.”

There was no urgency, only runners anticipating who would make the first mistake. Steve coasted in seventh past the finish for the first of twelve times. Coleman was borderline insulted at the tepid nature of the pace, and, one surmises, so too was Steve as he moved up to fifth on the outside as they neared the first full lap. I kept wondering why one of those guys wouldn’t take it. They were just setting it up for Virén, Steve thought. Coleman noted that if they kept this pace up, Ron Clarke’s long standing 5,000-meter world record of 13:16.6 from 1966 would not be in jeopardy. After ninety seconds, the Russian Nikolay Sviridov throttled up, to which Coleman said, “And the nonsense has stopped, and the racing has started.”

Steve dropped back to ninth, running along the inside and drafting behind the leaders. Granted it was early in the race, but he wasn’t following his natural instincts. Finland’s Juha Väätäinen, the European champion, who had a “blistering kick,” according to Coleman, sat behind Steve four back from the rear. Virén ran last of them all. Two full passes by the finish— 600 meters—went in a lethargic 1:41, following a 71-second quarter mile. The first of the five kilometers ticked by in 2:46. Sensing little urgency, Steve, along with Bedford, quickly rose through the field to chase down the Russian, still in front. Beyond that, Coleman added, “There’s not much action out there at the moment, but there’s a great deal of thinking. These athletes puzzling out what to do about this.”

Coleman, ever measured, said, “Prefontaine can’t leave it to a short finish. He’s got to push from a lap and a half to two laps out.” Coleman pegged it, but Steve couldn’t give himself over to it yet, fully surrender to who he was in the biggest race on the biggest stage of his young life. He had said that if it’s a slow pace and he lost to a kicker who leached off the front, then he’d always wonder “What if…?”

Still, the pace crawled. Steve, back to seventh and having run just under four minutes of the race, coasted to the outside of Lane 1, still beside Bedford, these two front runners trapped mid-pack. Down the backstretch again, Steve’s arms swung casually. He was a stride ahead of Bedford. “One suspects that they’re all waiting for David Bedford,” Coleman said. Just as the field completed four laps, Bedford tripped on Steve, and Steve flailed, but regained his rhythm. He would suffer a hole in his left leg an inch-and-a-half long and an eighth of an inch deep. Back around the turn and straightening down the homestretch again, Steve peeked over his left shoulder at Gammoudi and then targeted Puttemans, who was just ahead. Steve momentarily brushed shoulders with Puttemans and angled to get near Stewart, who had been in third by himself behind McCafferty and Sviridov. Steve came into full view, that rounded chest thrust forward in stark contrast to the plywood-pectorals of just about every other wraith, 4:52 into the race, “Real burly for a middle-distance runner, cocky American, he believes in himself utterly,” Coleman said. At this point, Virén shot like a bullet up into the lead pack as Steve whipped a quick “holy-shit” look over his right shoulder. Gammoudi, as if pulled on a string, followed Virén, who by now had struck the lead five minutes into the race. Stewart threw his weight and pushed Gammoudi away so he could draft behind Virén with nine laps left and just over five minutes lapsed. As quickly as Steve had moved into the top three, he slipped right back to seventh. Steve now strung out wide in Lane 2 to avoid traffic, but taking on more distance than Virén, who hugged the inside as if painted there, as were Stewart and Gammoudi. In a comic twist, Steve ran right beside West Germany’s Norpoth, who once coasted off Steve’s shoulder for eleven laps in a 1971 race and then blew Steve off the track in a brutal, lasting kick. The entire field bunched into a ten-meter cluster, Virén still leading, Steve again accelerating up into fourth alongside Gammoudi, having just run 2,000 meters in 5:32.6.

At this moment, far, far later than anyone had predicted, Bedford all but sprinted to the spearhead of the pack. “The inevitable happens; they were all waiting for this,” called Coleman, “Bedford goes in front.” Gammoudi wiped his brow and Virén kept a watchful eye on Bedford’s feet, so close to tangling with his own. Almost a curse, Steve was back in seventh and in traffic, a terrible and dangerous place to be pinned. The pace did not quicken despite Bedford’s surge and the field remained bunched. Steve, again on the turn, swung out four runners wide into the middle of Lane 2, covering ever more ground as the race neared its halfway point. As if feeling the danger of all that extra distance, Steve sped up and moved into third place with Stewart to his left. “All of them still playing wait and see,” Coleman said as the Spaniard Javier Álvarez Salgado took his share of the lead. Anyone who knew Steve as a runner, knew his style, could sense his growing impatience. The race wasn’t supposed to be this slow for this long. Much of that banked on Bedford, but also much of it rested on the reputation—the very nature—of Steve himself. What was he waiting for?

A year and a half earlier, on March 20, 1971, an early track meet for the Ducks in Steve’s sophomore season, Dellinger wanted Steve not to run too hard, follow the leader through the first mile, then have at it the second mile. It caught everyone off guard. The Register-Guard wrote, “He looked like Steve Prefontaine. He ran like Steve Prefontaine. He even watched the scoreboard clock the way Steve Prefontaine watches it. But heck, it couldn’t be Steve Prefontaine. As every track nut worth his salt knows, Steve Prefontaine doesn’t sit back and let someone else set the pace.” But that one time in 1971 and again here at the Olympics, he was running counter to his style and to how he’d learned to run and dominate for the better part of the last five years.

A surge from McCafferty shuffled Bedford back several spots all while Virén skimmed the inner lane not taking an inch of extra distance. Steve, still in third, bent around the turn while they straightened out. Coming up on 2,500 meters complete, Steve maintained his advantage in third to the outside with no foot traffic before him. He quickly shot a look down at his feet as if maybe he took a spike, but it mattered little. The 80,000 people roared, flags waved. The tension grew and Steve casually sidled up to McCafferty and closed the gap on Álvarez Salgado, who had led for the past lap or more. Coleman said, “Still the race hasn’t really started.”

Down the stretch again, Steve snuck a look over his right shoulder, his brow deeply furrowed. Five laps remaining, Puttemans charged past Steve and, along the inside, there was Virén lengthening his stride, tucking in beside Steve’s swinging left arm. Väätäinen, trying to snake his way through on the inside, tapped Bedford to move aside. Bedford shrugged him off and Väätäinen flailed his arm in frustration. “And surely, somewhere, someone, must go,” Coleman said, imploring a runner to have the courage to break it wide open. Steve, again, was swallowed by traffic down on the inside in fifth place. They passed 3,000 meters in 8:20; for perspective, a month before, Steve set an American record in the 3,000 in Oslo in 7:44. Here, the race’s color commentator said, “The suspense must be appalling among those who haven’t total confidence in their sprinting ability.” When Steve saw two miles flash in 8:52, he knew he was in trouble. Not long ago, Steve had said, Nobody is going to win the gold medal after running an easy first two miles. Not with me. If I lose forcing the pace all the way, well, at least I can live with myself. On American soil, Steve never would have waited this long to assert himself, to make the race his own and bend the others to his will, win or lose. He was disillusioned that other runners wouldn’t take charge. The moment, to this point, had subsumed him, stolen his identity. But not any longer. Which meant only one thing…

Just shy of four laps remaining, Steve, at long last, made the move. Out in the middle of Lane 2, for the first time, with the assuredness they had all expected, Steve Prefontaine struck the front for the first time in the 5,000-meter final of the XX Olympiad at 9:23. “This is sure being left to the faster miler and Prefontaine believes it’s him,” Coleman said. “The American now committed.”

Those “3:59s” he’d been running, this was why. Steve briskly pushed the pace and the field that was once bunched into a 10-meter box strung out by 20. “The American in front, almost a cult of the United States. He’s sort of an athletic Beatle.” Coleman noted that all around the stadium American fans wore T-shirts saying “Go Pre.” Stewart stayed tight with Steve with anailing Bedford in third while Steve breathed the clean air from the front. “The Europeans say that he hasn’t really been in a war yet, but this boy’s got utter belief in himself and he’s inexperienced enough in many ways not to know how good the others are,” Coleman said.

“Go Pre” signs and yellow shirts freckled the crowd. Their guy was in front, leading the Olympics. Virén moved out from the rail and began a hard charge toward Steve so as not to let him go unchallenged in this final mile. All runners looked as if they were standing still when Virén uncorked some of that beautiful stride, “states his intention now,” with three laps remaining. Steve still led with Virén drafting. Stewart traveled in fourth with Gammoudi behind him and the field strung out ever more. At last, a clear lead pack of five established itself as the class of the world: Steve, Virén, Puttemans, Stewart, Gammoudi.

Virén ran collected and calm, and Steve started to show his signature strain, still flying, still in charge, chest-thrust and plowing, a style that had so endeared him to his “people” back home. “And suddenly it’s starting to happen and runners are losing touch,” called Coleman. Steve leaned hard into the turn with that head ever cocked to the side. Steve took a one-stride lead down the straightway with Virén taking a swift peek over his right shoulder where he saw Puttemans, Gammoudi, and Stewart, in that order.

Nearing two laps to go, Virén whooshed into the lead and Gammoudi—his strategy all too obvious—followed, leaving Steve in third. Puttemans gave chase, as did Stewart. “These five are clear,” Coleman said. A lap and three-quarters left and, “They really have left this one to the fastest finisher.” Steve ebbed to fourth into Gammoudi’s slipstream. 600 meters to go.

At that moment, Steve laid his belly down and thrust by Gammoudi into third, second, and back in front, a mad dash for gold. Steve put some daylight between him and Virén, about whom, Coleman said, “there’s almost a certainty about [Virén’s] running in the past six weeks that’s almost made winning seem inevitable.” Steve in front and down the straight for the next-to-last time, the arms pumped harder, the bear climbing on, these five well clear. Steve, in command, straightened down the stretch. “The chunky American driving for home!” Coleman said. Virén, sticking to Steve like a tick, kicked into another gear and turned over his superior foot speed, his elegant length, to pull even with Steve 50 meters from the bell. Gammoudi, too, would not let Virén and Steve run free, breezing past Puttemans—who hit the wall—leaving Stewart to ration speed and save ground in fourth, stalking.

What he appreciated, above all, was that they left them up even after he lost. If he was coming home on his shield, his people would carry him.

Steve was nearly in a full charge with 400 meters remaining. Virén, in a drive, passed Steve on the outside 15 meters from the finish on the second-to-last lap. By now, Gammoudi was shoulder to shoulder with Steve. Virén hit the line in front. “This time the bell!”

Virén charged on while Gammoudi climbed up into second, Steve in third down on the inside. The crowd was riotous in its collective fervor; the runners could barely hear their own breath or the sounds of foot strikes. Round the bend and Steve shot a look over his left shoulder. If he saw anything at all, it was Stewart about five meters back. Perhaps sensing that Stewart was cooked back in fourth, perhaps thinking that no matter what, the medals belonged to Virén, Gammoudi, and himself in an unknown order, Steve made a decision. With 300 meters to go, Steve swept to the outside of Gammoudi and let loose a monstrous sprint, “The American attacks on the outside!”

Parrying, Gammoudi cut Steve off, blocked his momentum, and zipped ahead of Virén by a stride. These three, so close, too close. At 12:52.5, Steve laid it all out in what would be a move his peers would question for decades. So many would say, you have one move at that time in the race, when the body is so desperately in oxygen debt that you can no longer overdraw, what they saw next hurt them as much as it was, no question, hurting Steve in the moment. His head wavering and his arms pumping so hard, Steve attacked Gammoudi again, this time 180 meters from the finish. Gammoudi veered over to block, which played right into Virén’s scheme. Though Gammoudi looked wounded by the battle, he had a bit more than Steve. All the while Virén watched and waited as did Stewart some 7 to 8 meters back, surveying the theater before him. “These are the medal men!” called Coleman.

Into the turn with roughly 150 meters remaining, Gammoudi moved ahead with “The Finn and the American gearing up for the final attack!”

Virén waited no more: he uncorked an impeccably timed kick. Steve again looked over his shoulder knowing that by now he had no chance at defeating the Tunisian and the Finn.

Steve tried on the final corner, he poured forth, but it was like Virén was dropped in at the top of the stretch. He burst in front of Steve and exploded past Gammoudi. In the replay, you see the moment when Steve knew he couldn’t keep up, that Virén was in another league. Immediately Steve looked behind him for new worries. At this moment, 110–120 meters or so from the finish, there was undeniably a sense of panic.

The crowd roared for Virén, chasing his second gold medal of the games. Gammoudi seemed to be practically standing still, so was Steve, and Stewart charged like a locomotive from the rear. “Virén goes for home! Gammoudi is bankrupt, so too is Prefontaine!”

By now Steve ran on dread, willing the finish to find him. His arms were no longer part of his body. He looked over his left shoulder, his right shoulder. Steve was never a kicker, not in the class of these great closers, but he knew the feeling of a runner gaining on him. Rare was it that he lost in the United States, but there were the few times in the mile when he felt the looming presence of the long striding Arne Kvalheim in 1971 or Roscoe Divine in 1970; when he knew in his bones he was clipped after leading for most, if not all the way. And here, in the final mile, Steve did what he could and had been swallowed by Virén and Gammoudi. The finish was just a few meters away…

“Stewart with a late run!”

Eyes wide, a peek over Steve’s right shoulder, the head wobbling, his body no longer collected, his feet turning over as if running up a dune. And there in his eyes was the fear of prey surrendering to the teeth of the hunter. One look, two, and Stewart at last pulled even with Steve 15 meters from the finish and, in a delicate mercy, passed him. Steve gave over to gravity. In that moment, he was closer to death than life, so gassed and tired, wasted. All that carried Steve across the finish line was momentum and the instinct to stay upright. “Prefontaine dies in the final strides!…The American bows his head desperately.”

It was over.

Virén had won in 13:26.4, Gammoudi second, Stewart third; Steve, fourth, in 13:28.4, .8 seconds behind Stewart.

Steve pushed a finger onto his nostril and blew his nose. He hung his head low and he walked a wobbly line. He whipped the hair out of his eyes. He stared at the ground and soon took off his spikes to free his feet, pale as ghosts, from burden. Steve, his skin the color of the medal he just missed, walked across the track and onto the grass.

When he looked up, he saw the “Go Pre” banners still slung over the fences. What he appreciated, above all, was that they left them up even after he lost. If he was coming home on his shield, his people would carry him.

__________________________________

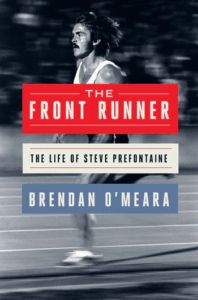

From the book The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine by Brendan O’Meara. Copyright © 2025 by Brendan O’Meara. To be published on May 20, 2025 by Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Brendan O’Meara

Brendan O’Meara is a journalist and author of The Front Runner: The Life of Steve Prefontaine (Mariner Books). Since 2013, he has hosted The Creative Nonfiction Podcast where he talks to writers about the art and craft of telling true stories. You can follow him on Instagram @creativenonfictionpodcast and subscribe to his two monthly newsletters, Rage Against the Algorithm and Pitch Club.