Chloé Hilliard on Confronting Racist Stereotypes in Hollywood's Casting Rooms

"Hollywood doesn’t like their black women subtle."

During the silent and golden age of Hollywood, films with an all-black cast were known as “race films,” not to be confused with blackface, where a white actor like Judy Garland or Fred Astaire pretended to be black in a major motion picture film. Race films were shown at “black only” theaters or segregated ones, but at certain times, usually matinee and midnight screenings.

In the early days, roles for black women were either that of the help or the temptress. The first black woman to win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress was Hattie McDaniel in 1940 for playing a maid named Mammy in Gone with the Wind. For every Hattie McDaniel, who famously said she’d rather play a maid on film than be one in real life, there was a Lena Horne, whose beauty and singing voice meant she complemented the white cast but was limited to being a lounge singer who entertained them but rarely interacted with them. The intermingling of races was heavily restricted in Hollywood movies; Southern audiences would walk out of the theater or become violent. The studios’ solution? Give black actors solo scenes that would be cut from the film when it showed in the south.

As Hollywood progressed, so did the types of roles black women played. By the 1950s the mammy and background beauty evolved into several still-problematic archetypes:

Mammy: Overweight, dark-skinned woman, domestic worker who cooks and cleans with a smile on her face. Her purpose in life is to make others, usually her white employers, happy. Aunt Jemima, the Popeyes spokescharacter, Annie, and the Pine-Sol lady are all modern examples of Mammy. Let’s not forget the highly acclaimed and problematic 2011 film The Help. Even Viola Davis felt compelled to apologize for her part in the modern mammy porn.

Jezebel: Named after a blood- and power-thirsty queen in the Bible whose beauty, enhanced with cosmetics, hypnotized men into doing her bidding even at the risk of their own lives. By this definition, Scandal’s Olivia Pope was a jezebel. Come on, don’t act like she wasn’t fucking the president of the United States and getting people kidnapped while her hair and outfits slayed.

Matriarch: Another physically big woman who cooked and cleaned, but unlike Mammy, she was wise and devoted to the protection and upliftment of her family. Tyler Perry’s Madea is the overexaggeration of this.

Tragic Mulatto: Biracial beauty queen who always manages to have far more European attributes than black (i.e., fair skin and long curly hair). Caught in between two worlds, she finds herself the object of both black and white men’s affection while being hated by women.

The Angry Black Woman: Brash and bitter. Perhaps the most notorious black female archetype not only perpetuated in media but also in everyday life. Originally this archetype was referred to as Sapphire, a character on the 1950s hit TV show Amos ’n Andy, who was overbearing, insufferable, emasculating, and undesirable.

Led to a small black box theater, I’m greeted by one of three white women sitting behind the camera. “Hi, Chloé! So nice to meet you.” The tiny platform stage creaked with every shift of my weight. “We’re going to ask you some questions, get your advice on different situations women find themselves in. Basically, it’s girl talk.”

“Got it.” I smiled and nodded. My replies were informative, concise, witty, and not good enough. They wanted jarring, crass, outrageous. Oh, and arm movements. They specifically told me to move my arms like those reality-TV people do in their confessionals. No one talks like that in real life. But I had to remember, this wasn’t real life.

“Think bigger,” one of them said. “We want you to fill the frame.”

I can accomplish the same things as a sassy black woman, without the bravado, but Hollywood doesn’t like their black women subtle.

Ten years of being a journalist who prided herself on being an objective fly on the way did not prepare me for this. Yes, physically I was big, but that didn’t mean I had the personality to match. I’d spent years successfully minimizing my presence. My polished disposition frustrated them. I couldn’t see their faces, but I could feel their disappoint in my inability to deliver. With no other direction left to give, they pulled out the big guns.

“Okay, Chloé, your answers are great but, ehh, we need to see more sassiness.”

“Yes!” the others agreed. All three of them broke into a side conversation about sass.

“That’s the perfect word. I was looking for that this entire time.”

“Chloé, can you be sassy?”

Sassy sas·sy /’sase/

adjective: sassy; comparative adjective: sassier; superlative adjective: sassiest; lively, bold, and full of spirit; cheeky.

The sassy black woman combines attributes from mammy, jezebel, and the angry black woman. She’s caring but not a pushover. She’s flirty but not a whore. She’s direct but not “call the cops” threatening. All of this makes her the perfect supporting character. She’s the sassy, loud, tell-it-like-it-is coworker or best friend. She has a catchphrase and rolls her eyes and neck for punctuation. She’s the comedic relief, devoid of shame. The type to throw herself on a man she knows she’ll never get and bounces back from rejection because she’s emotionally impenetrable. Above all, she is loud and at times embarrassing.

The sassy black friend’s look depends on who she is playing opposite. Yes, there is a science to it. If her screen mate is a white woman, the black friend can be gorgeous like Stacey Dash in Clueless. Dash’s character was rich, pretty, and petite and, in my opinion, better all-around than the lead. She was also black, and in a white film, the black friend, no matter how stunning, is never a threat to the white main character’s story. However, if both women are black, the sassy black friend must be a big girl. Her weight is the reason she isn’t seen as a threat to the cute, slim, black female lead. 2017’s Girls Trip slightly broke the mold by featuring four black women. The sassiest of the group was the comedic foil, undercutting the most tense situations, but at its core the film was about the married, slim, and super successful Ryan, played by Regina Hall, and the larger, single, and broke Sasha, played by Queen Latifah. I bet Latifah went into the first meeting and told them she wasn’t going to be the stereotypical loudmouth. She did that already in Bringing Down the House. Never again. The Queen is a jazz singer now.

The role I was auditioning for was opposite a petite black woman, hence why all the women in the waiting room were stressing out the folding chairs. I’m big but I don’t have a big personality. When I speak, it’s because I have something constructive to say, not a desire to be seen and heard at all times. Yelling isn’t part of my everyday emotional range. I can accomplish the same things as a sassy black woman, without the bravado, but Hollywood doesn’t like their black women subtle.

Hi Chloé— I spotted you at a comedy show the other night and would love for you to come in and read for a recurring role. Her name is Tanya, 30s, single, who is always looking for a hot date. The perfect sassy wingwoman, life of the party. She’s the lead’s neighbor.

Pass.

Hi Chloé— We’re looking to cast the role of Gaby. She’s the lead’s cubicle mate/office manager who keeps everyone in check with her sassy attitude and street smarts . . .

Delete.

Hello Chloé— Are you available to come in and read for Joanette, the sassiest teacher at Thomas Elementary . . . ?

I’m good, love, enjoy.

Nell Carter was a Tony- and Emmy Award-winning theater actress and singer. She started her career in 1970, eventually landing on TV with a starring role in the 1980s hit sitcom Gimme a Break! The official description of her character, Nell Harper, lists her as a housekeeper, which was just a nicer way of saying mammy at the time. The show’s plot could have been plucked out of Hattie McDaniel’s era. Nell Harper, a singer, befriends a white woman after running away from her Southern home at eighteen. Black best friend? Check. When Nell’s white bestie falls ill with cancer, Nell promises to move in and help take care of her family, which includes a stern police chief husband and three teen daughters. Caregiver and domestic? Double check. Nell’s character occasionally broke out in song. Shuckin’ and jivin’? Check. All that was missing from this racially insensitive gumbo was blackface. Oh, wait, there was an episode when one of the characters, a young Joey Lawrence, wore blackface to perform at Nell’s church event. WTF? Check.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad Nell was able to star in her own hit show for six seasons; however, this did little to advance the image of black women in American homes. Even though it was 1981-1987, people still found comfort and joy in watching a black woman dote on a white widower and his three kids. The only other black maid on TV at the time was Florence on The Jeffersons (1975-1985) whose “don’t give a damn” attitude shattered the mammy mold. As a kid sitting in front of the tube, I missed all that made Gimme a Break! problematic. I’m also the only person I know who loved Richard Pryor’s film The Toy. I stumbled upon it one Saturday afternoon as a kid and became obsessed with it. I won’t ruin the plot, but my parents had a hard time convincing me that people, especially black people, hated the film. It’s Richard Pryor! Living in a Hasidic Jewish neighborhood and attending all-black schools meant I was naive to a lot.

I watched Gimme a Break!, wishing I could sit on Nell’s lap and be engulfed by one of her hugs. I bet they were so warm, like fresh-baked cookies, her boobies soft like pillows, and she smelled like cinnamon or fried chicken, since she was always cooking something for her white family. My mother’s hugs were great, but my mom was slim. Slim hugs are no match for big-woman hugs. Their arm flab warms your neck like a chinchilla scarf. Why am I going down memory lane? Because Nell was the quintessential Sassy Black Woman, and for decades Hollywood wanted to cast this type of character, and in a small way they still do.

Auditioning made me take myself seriously as a product. No one wants to think of themselves as being bought and sold, but that’s all entertainment is. Are you sellable? Will you generate big money? I’d been approaching these roles as a realistic extension of who I am, which is why I rarely booked anything. Serious actors make themselves a vessel for the character to pour into. I’d read over lines, compelled to change them because “a real black woman wouldn’t say no crap like this.” I was too tied to reality. That’s why I stunk at improv.

Three years into doing stand-up, fully committed to living the dream, I applied for and received a diversity scholarship to a respected improv company. Quickly, I connected with the other two cynics in the class. The three of us sat in the back corner, cutting each other looks at the fantasy fuckery going on. Improv is the world of “yes, and” building on whatever is presented to you. However, I was taught long ago not to just go along with things. That’s how my people ended up on a boat in the Middle Passage.

“Everyone, let’s get in a circle.” Our instructor was an improv vet who dressed like a hipster greaser. We moved our rows of chairs out of the way and joined in the middle of the classroom like kindergarteners. I’m in my thirties; this feels dumb. “Okay, we’re going to take turns tossing a baby. Imagine there is a six-month-old baby and we’re tossing it in the air and across to someone. Great, now I’m gonna add a knife into the game. Remember you are catching a knife and a baby, those catches should have two different reactions.” After each class I walked out with a knot in my chest. I needed to yell, “The emperor has no clothes on!” Something about playing games with grown-ass people four hours a week felt insane. Then it dawned on me. I’m not fitting in because I’m a black woman and improv is about feeding your imagination, which if you are a person of color navigating this unfair world, you don’t have time for. I call it the “luxury of imagination.” White people have all the time in the world to play fantasy games, like Dungeons & Dragons and Quidditch, because they aren’t bogged down with constantly validating their existence to the world.

If I was going to be more serious about acting, I had to address my weight. I refused to be typecast as the mammy.

Being black in America means always being aware of your surroundings, how you carry yourself, approaching every situation with caution even if the danger is not yet present. To be black in America means you must master all five senses and develop the sixth, intuition, to keep your ass out of harm’s way. Improv was asking me to suspend reality, be vulnerable, and just go forward aimlessly. I felt like every time I stepped into class my ancestors collectively shook their heads in disappoint. Child, we didn’t die for you to toss a fake baby in the air. The revolution ain’t going to be a game.

“Chloé, you’re a tree.”

“Okay, but like, we’re in a Laundromat, so how about I be a person since we’re folding clothes.”

“Chloé, remember, the only rule to improv is ‘yes, and . . .’”

“Yes, and I don’t want to be a tree.”

Committed to moving past my mental blocks, I started raising my hand first to play in a scene. I was getting the hang of it until Mac started being my scene partner. Mac was an early-twentysomething white woman with greasy hair that always looked two days away from forming dreadlocks. She dressed like Stevie Nicks, which earned her the nickname Fleetwood Mac or Mac for short from my cynical friends and me. At first I thought it was a fluke, but my friends confirmed that she waited for my hand to go up before raising hers. Okay, she’s on my dick. No big deal. I’ll yes and roll with it. Teacher Greaser would throw out a scenario. “Ladies, you are in a coffee shop. Go!” I pull up a chair and mime reading a book while drinking a coffee. Up walks Mac.

“Hey, GIRLFRIEND! What up?”

Game over. What the fuck is this black voice she’s doing.

Before I can open my mouth, here goes the teacher. “Chloé,” he’s pleading with me. His experience teaching at this school, dealing with other diversity scholarship winners, he knew I was about to lose it on Little Dirtilocks. “Remember, the game here.”

I shook it off. Let’s try again. I looked up at her annoying face.

“Hi, how are you today?” I’m deliberate and proper in my response.

“You know how hard it is for us out there.”

“No.” I pause my character. “I do not know.”

“Chloé, ‘yes, and,’ let’s stick to the ‘yes and.’” The teacher was on the edge of his seat, hoping I would move past Mac’s black woman cosplay and find the true life-altering lesson of improv. I was happy to disappoint him.

“What is she doing?” I needed answers. Mac played innocent, claiming she was just getting into character. It felt like they were gaslighting me. I wasn’t crazy. These improv people were crazy, living in their heads because their real lives lacked adventure.

After Improv 101, I appreciated acting a little more. Acting has clear parameters. No matter how far you take things emotionally, there are still lines on the page that guide you until the end. In my opinion, improv had no map, no end, no emotional motivation. Improv will have you drive over a cliff to see how far the “game” can go. I’m too old for that crap. I need to know where we going, why, and who all is coming. Are those people friends, family, coworkers? So many questions for your dumb little “yes and . . .” asses. Again, luxury of imagination.

If I was going to be more serious about acting, I had to address my weight. I refused to be typecast as the mammy. As a new actor, your look is everything until people learn to appreciate your skill and the uniqueness you bring to a screen. Otherwise you walk into an audition needing to check off boxes. Black, fat, loud, funny, sassy. Thing is, I wasn’t fat fat anymore. After breaking up with Quentin and seeing how big I was on my early comedy tapes, I hired a trainer and lost most of the love weight I put on, leaving me in this in-between stage that could make it hard for me to land roles. “You’re too small to play the fat sassy friend and too big to play the token black friend. You either need to gain weight or lose more weight.” Those were real words of advice. As much as I wanted to argue this theory, I couldn’t.

Black women on TV and film still largely fell into two body types—plus-size or petite. I wasn’t about to gain fifty pounds just so I could play the sassy school guard on a Nickelodeon show, nor was I disciplined enough to lose another fifty so I could land the role of a sassy secretary in a white law firm on NBC. Whichever way you look when you break into Hollywood, that’s the look you have to keep for a long time. Take Halle Berry. We all looked at her crazy when she tried to grow her hair out. She had to rock with her Mario Bros. mushroom cut for decades, and even now when you see her with long hair you have to remember, oh, yeah, that’s Halle Berry. Why do you think actors spend so much money on looking youthful, or getting the same exact highlights and haircut? You freeze yourself in time. Signature looks are key. If I broke onto the scene as another big girl, the only way my weight loss would be accepted was if I became a spokesperson and client of a weight-loss program. Sorry, I’m not about to count points and dance in a commercial to elevator music while eating a dry, low-fat, sugar-free cookie just so the world will accept me shedding pounds.

After breaking my neck and undermining my integrity for way too many soul-crushing auditions, I had to come to terms with the fact that I wasn’t willing or able to deliver the industry’s off-base definition of a black woman. It was best that I focused on comedy. It was the one place the world couldn’t tell me what or how to be.

__________________________________

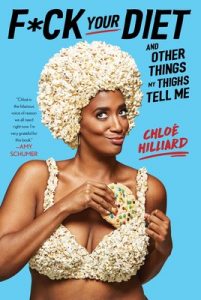

From F*ck Your Diet by Chloé Hilliard. Copyright © 2020 by Chloé Hilliard. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Chloé Hilliard

Chloé Hilliard is a writer and comedian who first appeared as a semi-finalist on NBC’s Last Comic Standing and went on to appear on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, Comedy Central, MTV, VH1, and more. Prior to her comedy career, she was a culture and entertainment journalist whose work has been featured in The Village Voice, Essence, Vibe, and The Source. Find out more at ChloeHilliard.com.