The world is in your head.

It can be, it must be in your head. The important thing is organizing the mind like an archive, a chest of drawers. What you do with the space around you, you can do with the space inside you. All is one. All is in all.

Thus the astrolabe you’re returning to that glass case must have an exact copy in your memory—the camera obscura of your brain. Same goes for this marvel of a painting, oil on canvas. And this sculpture. This ingenious little automaton. This oil lamp. Classification is essential. Once you’ve learned to do it with plants, become well versed in herbals, you can apply the same method to all of creation.

Quercus humilis. Cerrus. Ilex. Pullicortex. Mollifolia. Crassifolia.

Method. Precision. Store. Archive.

The world is in your head. And if God’s power enters intimately into everything, we who are the mirror of that power contain all of creation.

At times one may have the sense of being overwhelmed by the abundance of it; hence your breath catches, your heart skips at the countless rarities brought back by the German Fathers Grueber and Roth from their journey through vast China. Thanks are also due, Athanasius now thinks, to Father Martino Martini, one of his former students in mathematics, author of the Atlas Sinesis—he has given him so much information, and it is obvious to conclude that his keen intuition was honed by those studies in math. Thus the good Martini was reliable, as were the Fathers Grueber and Roth, who sought to spread Christianity throughout vast China to glorify the divine name. As the realms the Fathers traversed—a voyage never before undertaken by another European!—were unknown to geographers, and as the Fathers made many observations worthy of note about the dress, customs, habits of those lands, they entrusted him with their drawings and notes so as to contribute to the volume that Athanasius Kircher set out to create: Athanasii Kircheri e Soc. Jesu China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis Naturae et artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, auspiciis Leopoldi primi, Roman. Imper. Semper augusti Munificentissimi Mecaenatis.

Through their eyes, he sees the famed walls—the Fathers, leaving Peking, reached them in two months. An prodigious fortress against the Tartars. They’re so wide that six horses could race down it side by side without crossing paths. Even just the blowing wind, the cool wind blowing from the desert nearby, deserves mention. Oh, and everywhere around, there are all sorts of wild animals to be found.

Tigers. Lions. Elephants. Rhinoceroses. Leopards. Bulls. Unicorns.

Leaving the huge walls, the Fathers found a river filled with fish. Crossing this river, called the Yellow, the Fathers came to the great Kalmak desert, barren and rugged. Desolate. The inhabitants wander around the desert in order to steal. For this reason it is advisable for a caravan to be equipped with a band of guards to ward off attacks. Athanasius transcribes, adapts. Stiches, organizes. He looks in satisfaction at the whole, the chaos taking shape.

Athanasius knows he’ll have to devote his energies to this undertaking down to the last drop of ink.

Part One, Chapter One: Explication of the Sino-Nestorian Monument at Xian. With the utmost rigor, Athanasius reproduces the Chinese and Syriac inscriptions. His efforts have the effect of irrefutably demonstrating that the stele in question is evidence of a rare Catholic presence in vast China.

Part Two: Various Trips Made to China. All this gives him a subtle yet intense pleasure, an electric excitement that makes his fingers tremble. All this! It’s like recreating creation. Line by line, page by page, table by table. Each completed description corresponds to a feeling of relief, a calmer breath. Things assume clearer contours, definition, clarity. Description. You can’t see if you don’t describe. You can’t understand if you don’t describe. You can’t judge if you don’t describe. And judgment is one of the tasks of those who defend creation from the onslaught of Satan. At the same time Satan’s cunning and treachery have introduced horrible, detestable customs among those remote populations. He’ll need to discuss the benighted who worship the many-headed idols of the Chinese. He’ll need to linger on the pagan acts, unusual displays, abominable errors. Athanasius knows he’ll have to devote his energies to this undertaking down to the last drop of ink. He is well over sixty, the body doesn’t always meet our demands, but that’s why it is good to trust in God, gather in prayer, praise His name.

Another example of a false god can be found in Barantola. Figure VI shows its image: it is adored as the true living God; they even call it Eternal, Heavenly Father. The great devotion of this benighted population is bewildering. In subsequent chapters, he’ll have to address other ridiculous religious faiths. There’s no end to ineptitude, he thinks. He stops himself a moment before banging his fist on his desk. There are poor fools convinced there are seven seas in the world. The first is water, the second milk, the third curdled milk, the fourth butter, the fifth salt, the sixth sugar, and the seventh wine. In the water, they say, there are five heavens.

Such solemn idiocy. Athanasius Kircher’s drive is renewed. The stupidity and ignorance of others encourage him, motivate him. The great task that God has assigned learned men like him is at once simple and difficult: to reveal the truth. Simple if the mind is open to His light, guided by it. Difficult because Satan’s cunning and treachery hinder truth’s revelation. But we mustn’t give in, Athanasius, Kircher says to himself. And he bows his head over the paper once again. And he transcribes, adapts. Stitches. Organizes. He looks in satisfaction at the whole, the chaos taking shape. The imposing, majestic work he was to complete—China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis Naturae et artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata—is the best possible offering: the most true, most irrefutable work on what of that vast and remote region the missionaries’ eyes have seen and his own eyes have clarified and amended and ordered and judged.

The wrath of the devil that fills the world with hatred and deceit can be fought, yes indeed—by the product of the intellect of a man like him, able to recognize and therefore condemn the superstitious customs and demonic tricks and false beliefs lurking in that huge, immeasurable land, which no one should find marvelous and which, evidently, he never felt the need to visit.

__________________________________

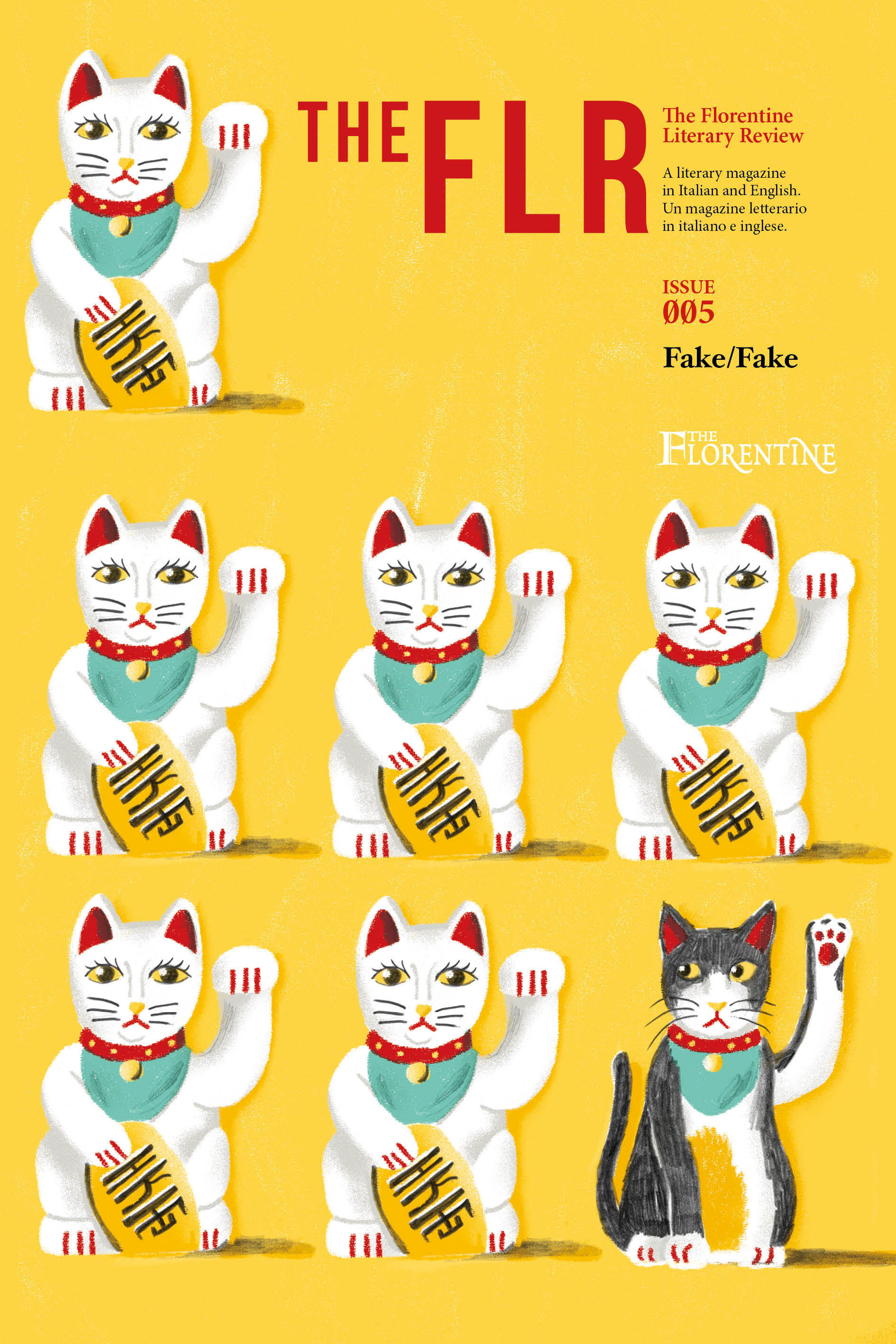

From “China Illustrata” published in The Florentine Literary Review Issue 5 (2019) entitled “Fake.” Used with permission.