Tim, Carl, and Paul hit the turn onto Reformatory Road just after 6:15. Rain now rips over the road in dense horizontal sheets. Objects plunge through the air like knots of sparrows. Carl rounds the corner and guns it north, with conditions pushing the Cobalt to its limits. Each second is precious. Whether or not they realize it, the tornado is lunging for them.

The moment they crossed into the core flow, with debris ringing off of the Cobalt’s frame, the vortex snapped its jaws to the northeast, just as Tim had warned. Reformatory becomes an escape route. If not for their turn here, the vehicle would have been overtaken.

Even after Tim has predicted its next move, the hair’s-width margin comes as a shock. This tornado is far larger, and moving far faster, than they could have expected.

The white Cobalt now shoulders through an inflow current like a boat struggling upriver. It’s harrowing driving, but they’re able to open up a buffer. Judging by the chatter in the car, they’re relieved to be out ahead of the beast. They plot their next maneuvers: “Now we go up north,” Tim says, “then east.”

Distance, however, does not gain them perspective. The stiff south-bound inflow winds are attended by a slug of rain winding centrifugally around the tornado’s northern flank. What had once been so clear, so readily tracked, quickly dissolves into the gray. Only chasers to the south of the storm can see the tornado now.

As they make their way farther north and plot a new route, Tim’s phone rings. It’s a New York producer with whom he’s been working, calling for an update at a particularly inopportune time. “Yeah, yeah. We’re at . . . the tornado is about 500 yards away. I really can’t talk right now!” Tim says. “It’s just south of El Reno. It’s gonna be on the ground for a long time, and it’s heading right for Oklahoma City.”

Tim does his level best to end the phone call quickly, but in a burst of pique, it sounds as though he mutters “Goddamnit!” under his breath. He hangs up after 45 seconds. It must seem like an eternity under the circumstances.

A mile up Reformatory Road, Carl swings east again onto Reuter. They’re still angling for an intercept, even though they’ve been given every reason to abandon it. Between the untimely dead end at the airport, the perilous push to the south, and their brief penetration of the debris core, the chase has proven problematic from the first.

But Tim isn’t the same chaser he was on that dirt road near Last Chance some 20 years ago, or even at Manchester. He’s spent so much time in the presence of violent storms that the old pang of fear has dulled. And while he has often said that nothing scares him more than the tornado he can’t see, he and Carl have penetrated the rain before not knowing what awaited them on the other side. No-man’s-land is where Tim found his greatest victories. He has succeeded by toeing the line between danger and safety. And as he’s gotten better, that instinctual border has drawn closer and closer to the storm’s deadliest winds. He’s broken or stretched chasing’s cautionary rule so many times it no longer has the same hold. He is like the expert climber who knows he can succeed without a rope—who’s felt each hold and scaled each pitch a hundred times. In the back of Tim’s mind, he knows it can always get worse; but his instincts haven’t warned him off today’s chase.

He must be curious. He must want to see what is behind the rain. Tim has never encountered this kind of storm motion before. He has never seen anything that careens to the south, the east, then northeast. Perhaps it is the fog of the chase, but he seems to think they have turned a corner, and that their lot is about to improve. After miles of shuddering over dirt roads, Reuter transitions to asphalt. The vortex seems to be easing more easterly. Now that they’ve established a reasonable buffer, this is their chance to regain lost ground. After a year’s hiatus, perhaps Tim thinks TWISTEX, even in its diminished state, will make history today.

“Disagree as they have in the past, this time Tim and Carl are in perfect accord about their next move. They are not giving up on the storm of their lives.”

Still, trouble hounds every providential development. For some 500 yards, they drive on in the blind, their view of the storm obstructed by a plains windbreak of thick red cedar. While Carl believes pavement will enable a highway pace, the north–south inflow buffeting the sedan continues to check his speed. The power lines to their right strum in the wind. Maintaining a straight heading requires his complete concentration. In half a mile, Reuter switches abruptly back to gravel. The Cobalt, built for city driving, not rally-style terrain, handles poorly on the dirt road, shimmying in the wind. In past TWISTEX missions, veteran operators of the mesonet sedans had refused to leave the pavement for this very reason.

Despite these conditions, Carl is determined to outrun whatever hides behind the rain, or at the very least to keep up. He is clocking between 40 and 50 miles per hour. Tim seems ill at ease, at one point loudly alerting Carl to an approaching stop sign.

“I see it!” he replies, with a touch of irritation. The men go silent for a while.

The next time Tim speaks, it is to note that the funnel remains out of sight, concealed behind the rain curtain. Without context, an observer could conclude that the dark mass of cloud bears nothing more worrisome than a ruinous deluge for the local dryland wheat crop. At its leading edge, though, the chasers may spot a crescent-shaped penumbra of centrifuged water, lit up by the weak early evening sun.

Something is shedding that rain, sending it spiraling onto the plains ahead.

By 6:18, as they near the intersection with Choctaw Avenue, a blue Toyota Yaris pulls onto Reuter from the north, no more than 50 yards ahead. The sound of wind-driven rain hisses against the windshield in swelling and slackening volume. The Cobalt bucks over a railroad crossing and speeds another half mile east before entering the wooded bottomlands that line a spur of Sixmile Creek. Once again, the sight lines to the south are fitfully blinkered by a belt of cottonwood and hackberry. A minute later, US 81, a divided, four-lane highway, lurches into view. At the intersection, Carl brings the Cobalt to a halt behind the Yaris.

Earlier, they had discussed diving south here. If Tim and Carl consult the weather service’s radar feed for evidence of the tornado’s location, the data will be of limited utility now. The last update refreshed nearly five minutes earlier, about the time they wriggled free of the core flow. When they peer south down the highway shortly after 6:19 pm, the radar’s obsolescence becomes chillingly apparent; they are astonished to see that they have failed to outpace the tornado.

US 81 disappears some 400 yards to the south, as if it has terminated at the foot of a sheer crag, rising above the highway with neither grade nor foothill. It swallows the horizon for more than two miles in either direction. If their eyes could penetrate the shadow and rain and dust, they would see vehicles tumbling.

Turning south is obviously out of the question. And with the tornado moving off rapidly to the east—or is it the northeast again?—heading north would mean placing themselves hopelessly out of position for the intercept.

“So, this is the highway . . .” Tim begins.

“Yeah.”

“We’re just gonna have to . . .”

“Keep on going,” Carl finishes Tim’s thought.

Disagree as they have in the past, this time Tim and Carl are in perfect accord about their next move. They are not giving up on the storm of their lives. To stay in the game, they must keep going east. The Cobalt crosses the highway’s four empty lanes and picks up the dirt road on the other side.

*

Carl races across the four lanes of US 81 and plows into the hanging traces of grit that billow behind the Toyota Yaris in front.

The trees thin and the red-bed plains slope gently before them. Carl’s outlook brightens. The rain is easing and the road ahead appears dry. It has cleared up enough that if they glance out Tim’s window just after 6:20 pm., they will sight the thin annulus and sod corona of a satellite vortex, no more than 250 yards distant.

After only eight seconds, though, it is ingested by what can only be described as an encroaching wall. Confusion begins to grip the men in the Cobalt. They have been flying down country roads at nearly 50 miles per hour, and they can’t seem to gain an inch. Tim suspects the tornado is racing at 40 miles per hour at least.

“The tornado isn’t gone; it’s just enormous.”

If Tim consults the latest radar scan from the nearest stationary Doppler, updated a minute before, he will note that it places the tornado core signature two miles to his southwest. But at this proximity he is likely chasing by sight alone. And this is just as well, because the radar is misleading. Much has changed in the last 60 seconds.

The tornado is steadily swallowing the distance. Just as the Cobalt passed US 81, the twister jagged to the northeast, even more severely than when they’d skirted the circulation just minutes ago. It isn’t only that it’s turning toward them, now; the tornado is expanding. It’s growing toward them. They’re not, as they’d thought, comfortably ahead; they’re on the knife’s edge.

Some 30 seconds later, the rain begins to fall with such ferocity that their windshield wipers can’t clear the water. The world around them closes in. Visibility is reduced to mere tens of yards.

Their grip on the increasingly sodden road is deteriorating, and a 70-mile-per-hour headwind out of the northeast further slows their progress. Given the amount of ground they have covered, Carl is still maintaining a quick pace despite the conditions, at least 40 to 50 miles per hour.

Their eyes strain to the south, searching. “Now I see it,” Carl says, “well, maybe I don’t.”

“It’s like it’s just a bunch of rain here,” Tim ventures.

Then, for the first time, he must begin to understand. There is no way of knowing exactly what Tim sees in the south, but the timbre of his voice shifts. It isn’t panic so much as a dawning comprehension: The tornado isn’t gone; it’s just enormous.

“In fact, uh, keep going. This is a very bad spot.”

With that, Carl’s DSLR camera goes silent, having reached the capacity of its five-gigabyte storage disk.

The camera pointing out the rear window of storm chaser Dan Robinson’s Toyota Yaris picks up where the audio recording leaves off.

From the moment the Cobalt crosses Highway 81, it is losing ground. The tornado sprints across the fields, its inflow battering the sedan. While Robinson pulls away from the gathering shadow, the darkness fastens itself to Tim, Carl, and Paul. The Chevy’s headlights dim and flare with the passing of intervening rain curtains, winking from view behind the gentle heave and fall of the prairie. Within a minute, beneath the lowering vault of tungsten-colored cloud, the headlights dwindle to a single, small point of light.

The Cobalt is now experiencing headwinds upward of 110 miles per hour. Its four cylinders are not equal to the task of hauling three grown men and three steel probes over a muddy road. They can manage no more than 20 to 30 miles per hour.

As the distance between Robinson’s camera and the storm grows, a dark wall fills the left edge of the frame. The vault lifts and the subvortex that has haunted the Cobalt’s trail since Reformatory Road now reveals itself. You’d have to catch it between the distortions of sheeting water on the rear window, but it’s there: a tower, black as shale and rising vertical from the earth, its base lapped by turbulent vortices.

Tim’s car is now well within the primary tornadic circulation. The more powerful subvortex closes in. The headlights glimmer once more at about 6:22 pm.

In all these years, Tim has learned to see the tics and patterns of the vortex. His probes aren’t all that have entered the unknown, glimpsing places no one alive had ever seen before. Tim has as well. And at these moments of extremity, it has always been his talent to see when the door is closing. He has always been able to find the seam, and to slip through to safety.

But this time, it is too late.

This is the tornado he can’t outrun.

The dark wall closes over the road, and the headlights are extinguished.

From the fleeing Yaris, this is the last living image of Tim Samaras, his son Paul, and Carl Young.

They have a little more than a minute left before the real killer—the subvortex—engulfs them. What they say to one another—whether there is time to say anything at all, or whether they even see it coming— remains a mystery.

But we do know what happens inside the storm, where no camera, no eye, can penetrate. Josh Wurman’s DOWs are still scanning. At around the time the tornado’s subvortex crosses US 81 and strikes the Weather Channel SUV, it becomes dislocated from its near-concentric loop around the core and is sent drifting outward. It begins to orbit the main tornado, describing a series of broad loops whose apexes manifest as tight curlicues, like the shapes a child might create with a Spirograph. Depending on its position, the velocity of the subvortex fluctuates drastically. Along the broad arc of the orbit, its speed increases exponentially as it races past the main circulation. But at each apex, the subvortex enters a tight curl that renders it nearly stationary, its high-speed winds scouring a single small area for seconds on end.

When the vortex reaches its first apex, Tim, Carl, and Paul are still within view behind Robinson. They have 130 seconds left. The subvortex arcs counterclockwise across the storm like the hand of some exquisite clockwork. Then it hooks rapidly across the southern rim of the tornado and slingshots to the northeast. More than 200 yards in width, it screams over the fields at up to 80 miles per hour. It sweeps toward zero hour as though it has been counting down.

“We do know what happens inside the storm, where no camera, no eye, can penetrate.”

With the storm moving over them from out of the south, the east is the last direction to which Tim would look for death to come. But shortly before 6:24 pm, the subvortex appears before them seemingly out of nowhere, as it curls into its second apex. The tip of the apex brings a 200-mile-per-hour killing wind down upon their location on Reuter Road, near a shallow, cottonwood-lined creek. For the next 20 seconds, with the car now inside, the subvortex remains nearly stationary. Its core lofts the Cobalt and carries it south into a field, then east, and northeast over Reuter. The car hurtles, plunges, and tumbles for some 656 yards, before coming to rest in a canola patch.

*

Canadian County sheriff’s deputy Doug Gerten locates the Chevy Cobalt in a field south of El Reno shortly before 7:00 that evening. He’s sitting in his Crown Victoria, a stout, seasoned investigator wearing a ball cap over his buzz cut. He watches marble-size hailstones shatter like glass against the hood as what’s left of the storm moves away to the northeast, toward Interstate 35 and points just west of Oklahoma City.

Some 40 yards to his north, Tim’s sedan is crushed nearly beyond recognition. Pieces are scattered across fields of wheat and canola on both sides of Reuter Road. For 15 minutes Gerten waits, until finally the hail stops falling. Then he steps out onto a prairie coated with ice in summer and wades through canola that has been matted flush with the earth, stumbling in its viney tangles.

He approaches the sedan and notes that the front end has been ripped away. The motor is gone. The rear end and the trunk are either in another field or have been compacted and thrust into the cabin. Little more than the chassis remains, and all but one of the tires is missing. The roof of the sedan is now no higher than Gerten’s hip. It took the car apart, except for the stuff that was welded together, he thinks.

Through the rear window, he sees a body on the front passenger side. He circles around and peers inside at a man lying prone on the seat, which has snapped and now reclines into the back. His legs are folded in the floorboard, draped in a deflated air bag. He looks middle-aged, with short gray hair that has gone white at the temples. He wears no shirt and no shoes, but his seat belt is still on. Gerten doesn‘t need to feel for a pulse because he knows what death looks like. He notices broken limbs and lacerations, but no other terribly significant injuries.

He calls the sedan’s tag number in to the dispatcher to see if he can determine the man’s identity. The registration comes back to a woman from Colorado, named Kathy. He thinks he knows the name Samaras, though he isn’t sure how.

Gerten spots a Jotto Desk affixed to the center console, which signals storm chaser; he knows they often mount laptops to such desks to track forecasts. He reaches inside the car and pulls a wallet from the man’s back pocket to find his driver’s license. He looks from the license to the man’s face, visible only in profile. Gerten knows who he is now. On that show about storm chasers, he had often seen this view of Tim’s profile when he stared up at tornadoes.

From this moment on, when Gerten communicates with dispatch about Timothy Michael Samaras, he’ll use his cell phone instead of the radio. Chasers often carry police scanners, and Gerten worries that if they hear about this, they’ll converge on the location. He dials dispatch and calls in the “signal 30.”

All through the evening and into the wee hours, Gerten remains with Tim, waiting on the state medical examiner’s office. A wrecker should be coming by to pull the Cobalt from the field. The fire department is on the way; they’ll free Tim from the sedan’s mangled chassis with the Jaws of Life. After an hour or two on the scene, Gerten gets a call from a fellow deputy up the road. The man has found Carl. His body is roughly 500 yards west of Tim’s, half-submerged in a ditch running high with rainwater. Paul won’t be found until the next morning, once the water has receded.

The night deepens as the firemen come and go, lighting up this stretch of dirt road in the farm country south of El Reno. In a few short hours, the sun will rise on a bad landscape that’s only going to look worse in the light of morning. Gerten stays with Tim through it all.

As he waits by the Cobalt in the dark, he remembers for some reason the opening credits of Storm Chasers. This is the memory he wants to linger after Tim Samaras’s last ride. The guys are standing together on an empty plains back road a lot like this one, posing in front of Tim’s gleaming GMC diesel, arms crossed and brows furrowed. There they stand in Gerten’s mind, looking to the horizon, raring to light out toward the next target somewhere off in Kansas.

__________________________________

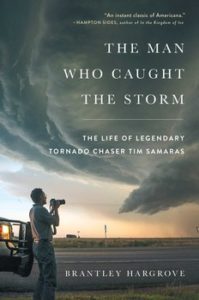

From The Man Who Caught the Storm: The Life of Legendary Tornado Chaser Tim Samaras. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2018 by Brantley Hargrove.

Brantley Hargrove

Brantley Hargrove is a journalist who has written for Wired, Popular Mechanics, and Texas Monthly. He’s gone inside the effort to reverse-engineer supertornadoes using supercomputers and has chased violent storms from the Great Plains down to the Texas coast. He lives in Dallas, Texas, with his wife, Renee, and their two cats. The Man Who Caught the Storm is his first book.