Charlie Jane Anders on World-Building and the Perils of Allegory

With Christopher Hermelin and Drew Broussard on So Many Damn Books

On So Many Damn Books, Christopher Hermelin (@cdhermelin) and Drew Broussard (@drewsof) talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in their hands.

This week, Charlie Jane Anders teleports into the Damn Library for a very sci-fi episode around her new novel, The City in the Middle of the Night. Anders talks tidally locked planets, the gargantuan effort it took to write her new novel, being accurate vs. writing a good story, and things to buy when you’re about to go on book tour. Plus, she brought an Ursula K. Le Guin novel, Five Ways to Forgiveness, and everyone gets to talking about the seductive world of writing sci-fi and how Le Guin is a master.

“I ended up with this sprawling mess, none of which was usable.”

So Many Damn Books: When I was reading this book, I kept thinking about the persistence of vision. There is this huge world that I feel like exists and I can see it, like referring to other parts of the world and it felt like a very complete vision. I’m curious: were you reading while writing this? How did you keep that persistence of vision going?

Charlie Jane Anders: The process of writing The City in the Middle of the Night was unlike anything else that I had ever written, and I’ve written a bunch of novels, including a number that never saw the light of day. This one was kind of a messy process—I mean, it’s always a messy process—but this one was kind of bad. I really obsessed with the idea of the tidally-locked planet, where there is the day side and the night side because those are real since most of the habitable planet in our galaxy are tidally locked. If we ever get out of the solar system we would be colonizing a planet like that.

So, I was sort of obsessed with that and trying to imagine it, and I basically spent a year and a half to two years just writing in notebooks, and I filled four or five blank journals with stuff. I was trying to get the story nailed down, but that never really happened with that phase of it. I just wrote tons and tons of stuff, and a lot of it just ended up being world building, like every aspect of human civilization on this planet and the alien civilization and everything else. Tons of stuff. What’s in the book is the very tip of that iceberg, but that’s what I had to do to write this story.

I was talking to lots of people. I was talking to scientists, and a friend of mine who had worked at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. I wouldn’t say I did research; I just kind of poked around and read a bunch of weird stuff and noodled around. Then I ended up with this sprawling mess, none of which was usable. I had a bunch of scenes that were garbage. But the world building is basically what’s in the book now. I’ve never had a book where the ramp-up phase of just figuring out the world took so long and was so complicated that by the time I was writing it, it was like, At least I know that stuff. I don’t know anything else, but I know that stuff.

*

“You get that kind of de-familiarization where you’re like, it’s a bison but has these crisscross, razor-sharp threads inside its mouth.“

CJA: Calling the alien creatures by earth animal names was kind of a cheat. I wanted to have this future world, but I don’t want to have names for things that are going to be like 20 consonants and a million weird symbols. I want to have everything to be easy to read. I wanted it to be names we already know for stuff, so “cat,” “dog,” “bison,” “crocodile,” whatever . . . I was like, what if it’s been translated to English and they just used the common English words instead of the words from the future? You get that kind of de-familiarization where you’re like, It’s a bison but has these crisscross, razor-sharp threads inside its mouth that will slice you to pieces in a split second and it has claws and scales.

*

“This is the story I have in my head and I want it to be poetic, weird, and a little bit fabulist.”

CJA: It was kind of a balance. To be honest, what I ended up with is not very scientifically accurate. I’m going to say that because I don’t want people to come back at me and I don’t want to be making any claims. I talked to some scientists . . . and I read some scientific papers and had conversations with people, but in the end I’m an imaginative writer more than I am a dutiful writer.

You know, nobody has actually visited any planet other than the moon, which is just our satellite, and so I kind of just wanted to imagine the strangeness and the complexity of it and the weird interaction between humans and this environment where we are the invasive species and where we brought a lot of stuff with us. Colonizing an exoplanet would be really weird, and in a variety of ways it would not be like living on earth.

I was heavily inspired by the real science that I read—and there are parts of the book that I can point out that because I read this thing I came up with this based on that—but in the end there are a lot of liberties that I took and a lot of stuff where I was like, this is the story I have in my head and I want it to be poetic, weird, and a little bit fabulist.

*

“Often the people who get most upset by allegory are the people you’re trying to represent or help them by showing their plight through allegory.”

CJA: The danger is you devolve into allegory, which is really seductive but often heavy-handed, preachy, and simplistic, and often the people who get most upset by allegory are the people you’re trying to represent or help them by showing their plight through allegory. The example I always think about is that one Star Trek episode where there are the people who are black on one side and white on the other side, and there are the other people who are black on the other side and white on the one side. They’ve been fighting a race war for however long, and two of each come on the Enterprise, and there are lots of speeches how they need to learn to live together but by the end they’re running around through some superimposed flames over their faces . . . and that’s an example of how allegory can be super heavy-handed and bludgeoning and not really helping anybody because it makes you feel kind of smug or self-satisfied to be like, I’m not like those people and I’m not as dumb as they are.

*

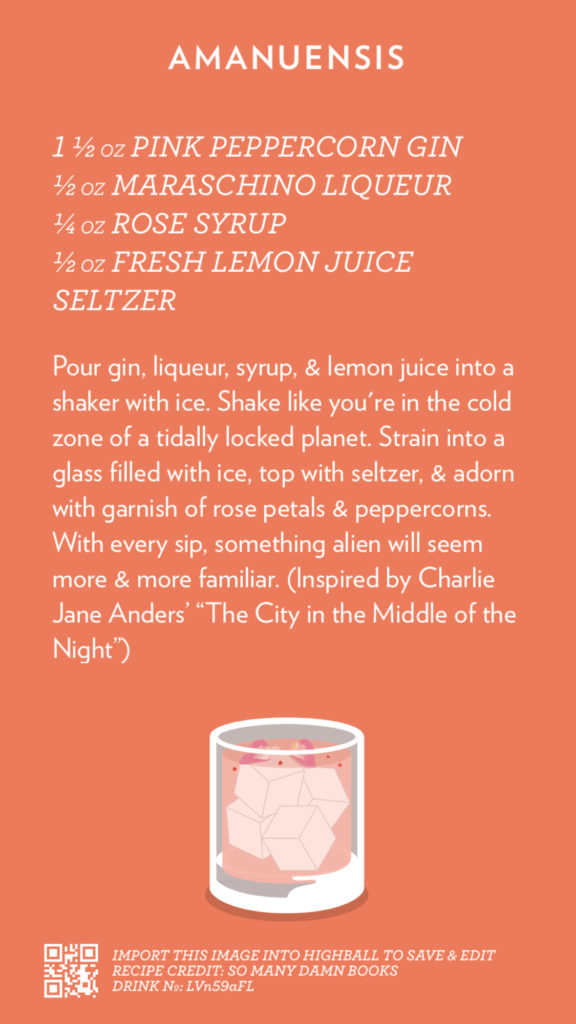

The recipe for this week’s themed drink:

So Many Damn Books

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.