Charles Dickens Had Serious Beef with America and Its Bad Manners

And How it Led to His Writing A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens’ unfettered joy at first arriving in Boston Harbor in 1842 reads like Ebenezer Scrooge’s awakening on Christmas morning. Biographer Peter Ackroyd reports that he flew up the steps of the Tremont House Hotel, sprang into the hall, and greeted a curious throng with a bright “Here we are!” He took to the streets that twinkling midnight in his shaggy fur coat, galloping over frozen snow, shouting out the names on shop signs, pulling bell-handles of doors as he passed—giddy with laughter—and even screamed with (one imagines) astonishment and delight at the sight of the old South Church. He had set at last upon the shores of “the Republic of my imagination.”

America returned his ardor. Though not quite 30, Dickens was a literary rock star, the most famous writer in the world, who landed like a conquering hero in a country swept up in an extreme “Boz-o-mania”—the hype of his tour then unprecedented in American history. He wrote his best friend, John Forster, that he didn’t know how to describe “the crowds that pour in and out the whole day; of the people that line the streets when I go out; of the cheering when I went to the theatre; of the copies of verse, letters of congratulations, welcomes of all kinds, balls, dinners, assemblies without end?” When Bostonians renamed their city “Boz-town,” New Yorkers determined to “outdollar . . . and outshine them.” Their great Boz Ball boasted flags, flowers, festoons, wreaths, a huge portrait of the author with a bald eagle overhead, chandeliers hung by gilded ropes, 22 tableaux from the great author’s works, and 3,000 guests, who consumed 50 hams, 50 tongues, 38,000 stewed and pickled oysters, and 4,000 candy kisses. “If I should live to grow old,” Dickens said, “the scenes of this and other evenings will shine as brightly to my dull eyes 50 years hence as now.”

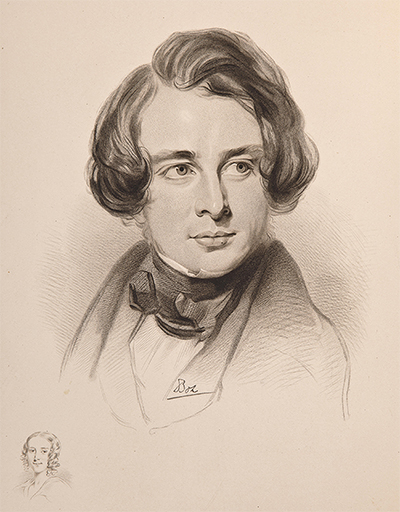

A sketch made of Dickens during his visit to America.

A sketch made of Dickens during his visit to America.

The Spirit of the Times wrote of it: “This most extraordinary, fashionable, brilliant, unique, grotesque, enchanting, bewitching, confounding, eye-dazzling, heart-delighting, superb, foolish and ridiculous fete . . . came off at the Park Theatre, New York, on Monday evening last.” But in a prescient endnote, the reporter predicted, “Such was the tom-foolery of silly-minded Americans, and such the ridiculous homage paid to a foreigner, who will in all probability return home and write a book abusing the whole nation for the excesses of a few consummate blockheads.”

In fact, Dickens wrote two.

His love affair with an idealized America was short-lived and hard-felt. Apart from the country’s great writers, he found Americans malodorous, ill-mannered and invading his privacy. “I am so enclosed and hemmed about with people, that I am exhausted from want of air,” Dickens complained to Forster. “I go to church for quiet, and there is a violent rush to the neighborhood of the pew I sit in. I take my seat in a railroad car, and the very conductor won’t leave me alone. I can’t drink a glass of water without having a hundred people looking down my throat.” On a tour of the Great Lakes he woke to a crowd gawking through his steamboat cabin window while his wife slept and he washed.

“He found Americans vulgar and insensitive, braggarts, hypocrites, and acquisitive beyond all imagining.”

He was repulsed by Americans’ table manners and the tobacco spit everywhere he looked—on even the sidewalks of the nation’s capital, where he found party politics contaminating everything, its leaders “the lice of God’s creation,” and “despicable trickery at elections; under-handed tamperings with public officers; and cowardly attacks upon opponents, with scurrilous newspapers for shields, and hired pens for daggers.”

Even worse, everyone wanted a piece of the action, from Tiffany’s selling unauthorized copies of his bust, to a barber selling locks of his hair. He found Americans vulgar and insensitive, braggarts, hypocrites, and acquisitive beyond all imagining. “I never knew what it was to feel disgust and contempt,” Dickens said, “‘till I travelled in America.” When he departed in June, he left behind all notions of an Arcadian realm he now regarded as “a vast countinghouse” full of nothing but “humbugs and bores.” (See: A Christmas Carol.)

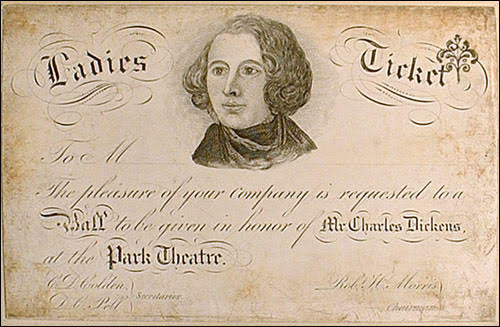

A ticket for one of Dickens’ public readings.

A ticket for one of Dickens’ public readings.

Americans had soured on him, too. Instead of graciously accepting their adulation, or reciting their better traits, Dickens never missed an opportunity to rail against them for copyright infringement—accusing American publishers of pilfering his work, which indeed they had—openly pirating his novels to sell for mere pennies, with no recompense to the author at all. The press took offense. Within a month of his arrival, Dickens had fallen from the literary firmament to the swamp, where they called out his “foppish” clothing and effeminate hair, describing him as “no gentleman,” “a contemptible Cockney,” “a mere mercenary scoundrel,” and a “penny-a-line loafer.”

American Notes for General Circulation, his scathing travelogue published on his return to England, did nothing to heal the rift. Dickens blasted America as a scam on a national scale. Instead of a democratic land of opportunity he described a land of opportunists—a nation of self-interested grubbers who cared only for politics and money—pretending at liberty and equality while condoning slavery, and a press “pimping and pandering for all degrees of vicious taste, and gorging with coined lies.” For good measure, he tossed in that nowhere else on the whole earth was there a nation of “so many intensified bores” entirely unable to laugh at themselves.

But that, apparently, was not enough. He followed it with a wicked satire of the country in a section of his next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, the whole of which was meant to be a strict diatribe on Selfishness and Greed. Peopled with characters alienated from each other and disconnected from themselves, it afforded him the chance to show Americans slurp, spit, and guzzle, and, most boorish of all, lick the communal butter knife.

“Instead of a democratic land of opportunity he described a land of opportunists—a nation of self-interested grubbers who cared only for politics and money—pretending at liberty and equality while condoning slavery.”

Americans hated them both. “We are all described as a filthy, gormandizing race,” raged an article in the Courier and Enquirer, calling Dickens a “low-bred scullion . . . who for more than half his life has lived in the stews of London.” The New York Herald called American Notes “The most trashy . . . most contemptible . . . the essence of balderdash reduced to the last drop of silliness and inanity.” Even Dickens’ friend, Thomas Carlyle, wrote that he “caused all Yankee-doodledom to blaze up like one universal soda bottle.”

But in a karmic turn of events, Martin Chuzzlewit was a flop. Despite a recession in the industry, Dickens was the most reliable top-seller; but if the Americans reviled the book, the English thought not much more of it. The first ever novel written under his own name, instead of the more loveable “Boz,” never sold more than 23,000 serial copies a month, compared to as many as 100,000 of his earlier work.

Dickens was crushed. “I think Chuzzlewit is in a hundred points immeasurably the best of my stories.” But his best book was his worst seller. When his publishers, Chapman and Hall, threatened to deduct from his pay 50 pounds sterling a month to repay advances already made, Dickens was in a bind. His house, family, expenses—including his commitment to his father, relatives, friends of relatives, and every worthwhile charity in London (some of which he’d started himself)—were outsized and near impossible to maintain. The great irony is that his “little Christmas book” came into being as a money-spinner to save him from financial ruin. (For a fiction writer, the perfect conflict.)

But A Christmas Carol was more than that. In six weeks, between two installments of Chuzzlewit, Dickens wrote a mere 45,000 words illuminating the true spirit of the holiday that was not about America, but all the world, and all of us, himself included. Its universal message of love and generosity as the antidote to selfishness and greed rang a bell everywhere it went. His great English rival, William Thackeray, called it “a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness.” And if it’s not a straight line from Dickens’ famed “quarrel with America,” to the writing of the second most beloved Christmas story in the world, it zigzags nicely. Even the American literary magazine, The Knickerbocker, wrote of it:

If in every alternate work that Mr. Dickens were to send to the London press he should find occasion to indulge in ridicule against alleged American peculiarities, or broad caricatures of our actual vanities, we could with the utmost cheerfulness pass them by unnoted and uncondemned, if he would only now and then present us with an intellectual creation so touching and beautiful as the one before us. Indeed, we can with truth say, that in our deliberate judgment, the ‘Christmas Carol’ is the most striking, the most picturesque, the most truthful, of all the limnings which have proceeded from its author’s pen. There is much mirth in the book, but more wisdom; wisdom of that kind which men possess who have gazed thoughtfully but kindly on human life, and have pierced deeper than their fellows into all the sunny nooks and dark recesses of the human breast.

We read it still. To shed light on our own nooks and recesses. To remember exquisite moments blessed with lucidity that, despite everything, it is a wonderful life. The way Christmas calls us to each other, to gather round the hearth, the flame, the warmth, the truth. To find Ebenezer Scrooge awaking on Christmas morning to a world renewed, and for himself, a second chance.

__________________________________

Samantha Silva’s novel Mr. Dickens and his Carol is available now from Flatiron Books.