As a child I would wait for the afternoons that my mother would spend up in her bed, tired (as my father called it), to creep into the living room, mute the volume and turn the TV to Channel 4.

I had first known that channel as an uncertain blackness that my father and I would visit on the nights he and I watched movies, and which would, since the input for the VCR ran through it, abruptly detonate into a static that, as if a violence done to the otherwise sequential logic of our cable package, vexed my father immensely. My father, who never disciplined me, never screamed nor used force, had always become terribly upset over minor events, and would grow disconsolate over clumsily dropped pieces of china, asking everyone in the house about fingerprints on the brass light-switch plates he’d installed in the living room and that frequently paused him with a presentation of his own image, miniaturized, and slightly warped by the indentation of the screws. After he returned from a business trip to India, he would, for years, over and over tell reluctantly obliging relatives and coworkers and acquaintances the story of how, on his first night staying at the Grand New Delhi, he had discovered that the reading light over his bed didn’t work, and when he had gone to the front desk to let the manager know, the manager had told him, rather cheerfully, that he could find a light bulb for himself, down the street, at the outdoor market. At this point in the story, my father would pause to look from face to coldly bemused face, his own expression so terrifically unguarded, so naively betrayed, that, later in life, I’d have to look away during the telling to save him from a second betrayal. Even as a child, I was careful to diminish with feigned inattention the scope of the treachery worked upon my father by Channel 4 when, with bitterness, he was forced to mute the volume before he typed in the channel number, and then, as soon as the VCR had turned on—me motionless as when he negotiated a particularly difficult turn on a road—to unmute it.

It was during these interims of static that my father so indignantly suffered that I discovered that images, desultory and faint and scrambled, would, every now and again, make their way through Channel 4. Abruptly the static would clarify—as in a vision, there was a context-less glimpse of a man talking (muted), the colors of his body, along with those of the ground and sky, inverted. But the image would quickly vanish from the screen in a blizzard of visual noise, and from my memory soon after, too. For in the same way those inchoate thoughts that occur outside of words, on the peripheries of sleep, are dispersed by the intrusion of known and named phenomena (say, a car alarm going off in the night), those hazy images would dissolve from both the screen and my thoughts as soon as the trailers started. And what made what arose on Channel 4 further unclear was that my father didn’t comment on it, nor did his face report seeing anything. It was as if I had hallucinated in a mild and forgivable way.

One night, as we were getting ready to watch Jurassic Park, the screen, down which white horizontal lines had been idly scrolling, all at once blinked to the image of a woman at the top of a staircase. It was only after the image vanished and the VCR turned on and the walls blushed with the red glow of the FBI warning against pirating that I realized she’d been wearing a robe, which she’d let drop. I did not, though, recognize the type of underwear she’d worn beneath or even that it was, in fact, underwear she was wearing. Like the intricacies of rhyme and meter in the poems my mother sometimes read me on the days she was feeling well, the complex interaction of straps and buckles she wore oppressed me with a feeling that was opaque and slippery and near holy in how far beyond my understanding it seemed, and perhaps for that reason impressed itself so powerfully upon me that I was, in that moment, ready to dedicate the rest of my life to deciphering it.

But I could find no immediate clues to my feeling. Apparently, my father, a foot away, eating popcorn at a measured pace, hadn’t seen what I had. So I sat still, staring at the trailers, stunned, burning, isolated by the already vanished image, much like the saints were (as I understood it at the time) by visions, which Father Cassidy, our priest, made analogous to Ohio State games every Sunday, my head propped in my hands in the third row next to my father. It was the feeling I’d get entering beneath the soaring vault—to cooler, blue-and-gold-hued air, heavy with frankincense and smoke and a hazy but growing expectation that was somehow magnified by the chambered hush of the room, and the spectral shifting of cotton on lacquered wood, and the royal tones of the stained glass windows—but long dissolved by an overwhelming boredom.

The woman returned to me in totality, or rather, since the image had been deformed beyond recognition, a nearly perfect echo of the image.

I did not think any more of the woman that night, making it the last night for a long time that I was to be un-haunted by her image. Because for months afterward, I would be sitting at the kitchen island, squint-eyed, showered, dressed in my Catholic school uniform, ready to eat cereal made somehow nauseating by the chill of the tiles under my socked feet and the urchin-colored darkness outside; or at my desk, history, narrated in brief by Mr. Valentine, unfolding at the front of the room; or, most often, lying in bed before going to sleep, when the image of the woman would return. Somewhat. Her immersion in memory had morphed and softened her features enough that I doubted what I’d seen, and sometimes whether I’d seen it at all. In any case, with each momentary and repeated attempt to recall it, the image—like a face in a Dalí landscape, shifting and warping and receding the harder I concentrated on it—affected me more and more weakly. And so, there were nights that, with the same guilt and relief and satisfaction I would feel years later, when having woken in the early hours of the morning with a certain phrase ringing in my mind, I’d decide, as I went back to bed, that it was not worth the trouble of writing down, I would conclude I’d only imagined seeing on Channel 4 what I couldn’t remember clearly in any case.

At that time, my mother entered into a period in which she rarely left her room. So my father had started dropping me off at school on his way to work, 30 minutes earlier than I was used to. And instead of waiting for my mother to pick me up, I had started taking the school bus back in the afternoons. It was on one such afternoon, riding the bus home—my head against the vibrating metal armature of the next bench, a hot rhombus of sunlight rumpling in my lap—that the woman returned to me in totality, or rather, since the image had been deformed beyond recognition, a nearly perfect echo of the image. As the robe dropped, I felt my breathlessness and diffidence as before something awful I’d done, some great crime I’d committed.

Stunned into a fugue, I walked down the block from the bus stop, careful to neither examine the feeling too closely and dissolve it under scrutiny, nor look at anything in the neighborhood long enough to be carried off into my habitual sense of existence. My eyes stayed unfocused as I turned (pretending not to see the timid wave of the elderly widower, Peter, who was often outside trimming bushes already Brunelleschian in the absolute symmetry of their lines, or raking a yard barren of leaves, and who with painful self-effacement would sometimes invite me to look at albums of himself and his deceased, Edna, standing in the sepia-toned light of the 1970s, in Rome, in Bucharest) into the former carriageway that led to our garage, our neighborhood passing far outside of me like a gallery of the mediocre Impressionism—featuring railroad crossings intersected by shadows, or the storefronts of the older buildings on Clifton Boulevard in peacock hues—that the artistes of our suburb of Cleveland worked in and which my mother had, at one point in her life, before the onset of these frequent episodes of being tired, patronized with gentle condescension, being herself an artist, but of glass.

That day, as I walked up the pathway to the door, I feared my mother would be feeling better, for the sight of her, at the stove, looking back at me from the pot of pasta sauce she was stirring, radiating normality, would, I sensed, inevitably destroy the delicate feelings I’d managed to transport safely from the bus stop. But when I entered the house and saw the unused stove in the unlit kitchen, I knew my mother was still upstairs and had to stifle my violent elation in order to preserve what impelled me to the living room for so vague a purpose that, after turning on the TV, muting it, and changing it to Channel 4, the static wasn’t on for more than a minute before I lost completely the sense of what I had been pursuing so that I couldn’t recall if I had even been looking for anything real in the first place. I was watching cartoons by the time my father’s arrival made me look up.

“Did you do your homework?”

Sprawled out on the tartan chair, I shook my head.

He sat down. “Where’s your mother?” he said. But he seemed to have asked the question out of the same indifferent politeness that causes people to ask how each other’s days are going. And indeed, without seeming to acknowledge my reply, he turned the television to Channel 5, which transitioned to local news before the game shows began. The sunlight, by then having passed over the roofs of the houses across the street, and under the lip of our porch, narrowed to a band on the floor that I stared at in the descending gloom, feeling myself, without knowing why, on the verge of weeping, my sense of hopelessness only doubled by the wordless knowledge that I wanted to punish my father with this crying, and that therefore I would be inconsolable, for I wouldn’t allow him to console me.

__________________________________

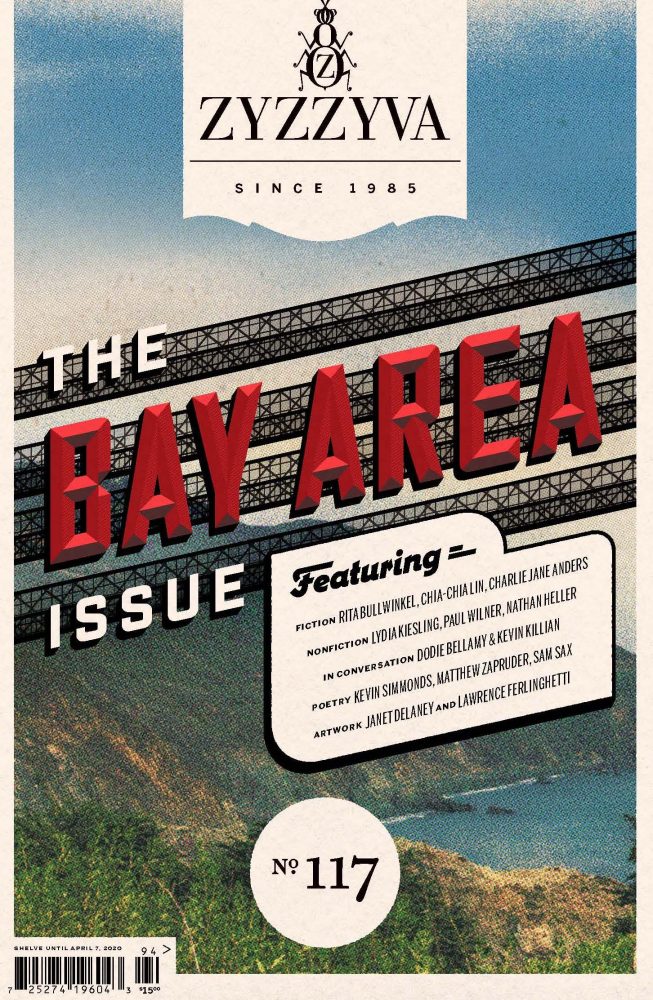

From “Channel 4” by Michael Sears, first published in ZYZZYVA, the Bay Area Issue (no 117). All rights reserved.