Catherine Newman on the Humor of the Unexpected

“Anything catching on fire and crashing through the chimney into the living room is funny—but it’s really funny if it’s raccoons.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

It’s embarrassing to decide to write a craft piece about humor. Like: I think I’m so funny! Like a pair of cartoon bluebirds has draped a sash over me with the word funny embroidered on it by a badger and now they’re helping me make a dress for the comedy awards ceremony, holding the seams together in their little beaks while I stitch them and sing a lovely, funny song about how lovely it is to be so funny and meanwhile two towns over a beast is turning into a prince because of how hilarious I turned out to be.

But I was thinking about humor and how some humor works, because my very funny friend, the Guncle writer Steven Rowley, recently sent me an email in which he referenced feeling dumb as a bucket of hair, and I laughed. It’s so good and funny because, among other reasons, how did the hair get in the bucket? You automatically picture the dumb clumps of it with nothing helpful to add to the conversation, but also maybe all the people walking around hairlessly? A bucket of rocks you might expect. But hair? I think that’s one way humor can work—there’s something you think you can predict, a metaphor usually, only then it either veers off in an unexpected direction or it extends past what you imagine its likely endpoint is into something deeply deranged and hyperbolic like you’re on the 1 train in NYC, and it turns out not be making local stops like you thought because it’s actually an express and you rocket past your station and all the way up to 96th and Broadway, where there are so many rats chewing on hot dogs in the bushes outside that you feel like you’re in a Wes Anderson movie.

For example: this, from comedic genius Samantha Irby’s book We Are Never Meeting in Real Life: “I feel my sexiness is a thing that creeps up on you, like mold on a loaf of corner-store bread you thought you’d get three more days out of.” Funny, funnier, funniest at every stop. Or, from the same book: “Real love feels less like a throbbing, pulsing animal begging for its freedom and beating against the inside of my chest and more like, ‘Hey, that place you like had fish tacos today and I got you some while I was out,’ as it sets a bag spotted with grease on the dining room table.” Or this, from her book Quietly Hostile: “I’m so embarrassed by everything all the time, humiliated even by the need to breathe air where other people can see me.” Everything is already funny to begin with—and then it hikes up out into the wilderness.

For example, this from memoirist Shalom Auslander’s Foreskin’s Lament: “My family and I are like oil and water,” he writes, invoking a cliché, “if oil could make water depressed and angry and want to kill itself.” (I added “he then subverts the cliché,” before remembering that a) you are smarter than a bucket of hair, and b) this is not the essay section of a final exam.) In a similar vein of banality gone bananas, this from Mindy Kaling: “I say if you love something, set it in a small cage and pester and smother it with love until it either loves you back or dies.” (To be totally transparent here, I had that quote in the list of funny things I write down, but then could not figure out where it came from and only found the Andy Bernard character on The Office saying, “I love you like a child, and I will never, ever let you go,” which was also funny but kind of hard to locate in the show and maybe written by AI, sorry, sorry.)

Or this, from a piece Anne Lamott wrote for Salon in 2002, which starts off heading amiably towards a familiar metaphor and then darts off the path: “Being on a book tour is like being on the seesaw when you’re a little kid. The excitement is in having someone to play with, and in rising up in the air, but then you’re at the mercy of those holding you down, and if it’s your older brother, or Paul Wolfowitz, they leap up, so that you crash down and get hurt.” Also Anne Lamott, from a 2003 Salon piece: “I spent my whole life helping my mother carry around her psychic trunks like a bitter bellhop.” Bitter bellhop! Embroider that on my sash.

Everything is already funny to begin with—and then it hikes up out into the wilderness.

For example, this from Dear Fang with Love, an earlier novel of the astonishing Rufi Thorpe who was recently longlisted for the 2025 Comedy Women in Print Prize for Margot’s Got Money Troubles: “I finally did sleep for a little while, only it was like the difference between Pringles and actual chips, like someone took sleep and then put it through a horrible industrial machine, made it into a paste, and re-formed it and baked it into a shape that was supposed to look like sleep but was not anything even close.”

And, for a final example, this from brilliant comedic writer Lorrie Moore’s story “Dance in America”:

“The thing to remember about love affairs,” says Simone, “is that they are all like having raccoons in your chimney.” […]

We have raccoons sometimes in our chimney,” explains Simone.

“And once we tried to smoke them out. We lit a fire, knowing they were there, but we hoped the smoke would cause them to scurry out the top and never come back. Instead, they caught on fire and came crashing down into our living room, all charred and in flames and running madly around until they dropped dead.” Simone swallows some wine. “Love affairs are like that,” she says. “They are all like that.”

Anything catching on fire and crashing through the chimney into the living room is funny—but it’s really funny if it’s raccoons. And it’s funniest if it’s all if it’s not just a metaphor for a love affair. It’s a metaphor for ALL love affairs. I’m sorry if I ruined it.

____________________________________

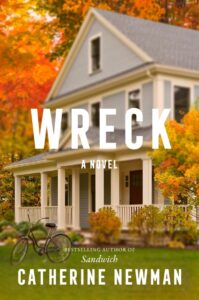

Wreck by Catherine Newman is available via Harper.

Catherine Newman

Catherine Newman is the New York Times bestselling author of the memoirs Catastrophic Happiness and Waiting for Birdy, the middle-grade novel One Mixed-Up Night, the kids’ craft book Stitch Camp, the best-selling how-to books for kids How to Be a Person and What Can I Say?, and the novels We All Want Impossible Things, Sandwich, and Wreck. Her books have been translated into a dozen languages. She has been a regular contributor to the New York Times, Real Simple, O, The Oprah Magazine, Cup of Jo, and many other publications. She writes Crone Sandwich on Substack and lives in Amherst, Massachusetts.