Catastrophe Awaits:

Nagasaki Before the Bomb

M.G. Sheftall Chronicles Daily Life in Japan At the End of the Second World War

Former Daiwa Textile plant North Ujina, Hiroshima

Two hundred fifty kilometers east-northeast of Nagasaki

3.7 kilometers southeast of Hiroshima Ground Zero (GZ)

August 9, 1945

*Article continues after advertisement

In his khaki serge kokuminfuku uniform and the white hachimaki headband of a Yamato stalwart, the short, bespectacled fifty‑four‑year‑old Professor Nishina Yoshio must have looked less like Japan’s preeminent nuclear physicist and more like a rural school principal presiding over a patriotic rally. His appearance would have been even more at odds considering that he was at present collecting evidence to support his initial informed gut‑reaction theory—already shared with the prime minister’s office the previous evening—that the Americans had destroyed Hiroshima with an atomic bomb. But he was going to need more quantitative empirical observations to put into the report his survey team would eventually submit to Imperial General Headquarters.

In lieu of Geiger-Müller tubes or other specialized detection equipment the team did not possess, Nishina had to come up with another method of acquiring incontrovertible evidence that physical matter in Hiroshima had been exposed to an extremely high dose of radiation delivered in an extremely short span of time. Toward this end, he asked the Akatsuki Maritime Command—the local IJA organization in charge of Hiroshima rescue and recovery—to provide his team with the bodies of bomb victims on which to perform autopsies. Specifically, he needed the bodies of people who had succumbed not to burns, blast force, or impact with ballistic objects but rather who had been killed at a molecular level—the genetic material in their cells shredded by the shower of gamma rays and neutrons that he knew, at least theoretically, would have been released by the detonation of an atomic fission weapon.

At least if he could help it, no one else’s grandchild was going to die on his watch because of a decision he made—or failed to make in time.

Among the at least 100,000 corpses strewn across Hiroshima at that moment and awaiting cremation, there would have been any number—perhaps even thousands—of bodies that fit the esteemed physicist’s needs. However, to avoid any jurisdictional (and ethical) issues that would have been involved in using civilian victims for this purpose without the permission of next of kin, the Akatsuki Command instead relied on a supply of bodies of individuals over whom the emperor’s military had incontestable authority. This morning, the outwardly unblemished remains of IJA soldiers collected for Professor Nishina’s autopsy requirements were lined up in the first aid room at the Daiwa Textile factory—the facility Akatsuki Command had requisitioned to serve as the headquarters for its training division.

For the first autopsy, an Army doctor named Kosaka made an incision into the abdominal section of the body of a young soldier. Without further ado, Nishina reached into the opened body cavity and held up a lump of internal organs that was closer in consistency to gelatin than it was to normal flesh.

“Does everyone see this?” Nishina asked the gathering of civilian scientists and military observers. “Make no mistake…This is internal organ destruction caused by an atomic bomb.”

For Nishina, this was the most convincing piece of evidence he had found so far to confirm his theory about what had destroyed Hiroshima. The following day, he and his colleagues would make their formal written report to that effect to Imperial General Headquarters.

*

Nagasaki Prefectural Office Edo-machi

Four hundred sixty meters west of Nigiwai Bridge

*

Two hundred fifty kilometers west of Professor Nishina’s grim autopsy session, Governor Nagano was preparing for the morning’s upcoming emergency meeting to discuss the civil defense implications of the American new‑type bomb. At 0748, warning alert sirens began wailing across the CBD. Two minutes later, when the sirens were upgraded to an air raid alert, Nagano instructed his secretary to contact the relevant department heads, police, and fire officials to inform them that the venue for the meeting would be changed to the prefectural civil defense bunker in Rokasu‑machi. There would be fewer distractions there, and the governor was going to want everyone’s full attention when he announced a decision he should have made weeks if not months earlier: He was going to order the immediate evacuation from the city of all members of the civilian population who were not otherwise directly engaged in essential war work. At least if he could help it, no one else’s grandchild was going to die on his watch because of a decision he made—or failed to make in time.

*

Nagasaki Appellate Court chief judge’s official residence Katsuyama-machi

Seven hundred meters northwest of Nigiwai Bridge

*

Ishida Masako woke up with the toothache that had been bothering her all summer. She had been meaning to see a dentist at some point, but her hectic daily schedule at Ōhashi—inclusive of her three hours of commuting every day—had so far precluded the luxury of receiving professional dental care. Judge Ishida—perhaps getting tired of hearing his daughter complaining about the ailment or, perhaps, having discussed the Hiroshima news with his daughter the night before and now harboring some unvoiced premonition of catastrophe—told Masako that he wanted her to take the day off from work to go get the tooth looked at. Besides, the household would be busy today, making the move to the new Nagasaki Appellate Court chief judge’s official residence, a few blocks over in Yaoya‑machi; perhaps his daughter could lend a hand with that after her dentist visit.

Masako, however, was having none of it. With the nation fighting for its very existence, it would have been untoward for an employee in a vital war plant—especially the daughter of such an important and highly visible public official—to take off from work on account of a little toothache. The judge relented in the face of his daughter’s determination, perhaps more than a little proud of her patriotic pluck.

Masako readied her work outfit while the three adult women of the house—Hayashi‑sensei and her mother and the Ishidas’ young live‑in maid, Yamaguchi Shige—went about their preparations for the day, beginning with breakfast. As Masako had started on her job too late to receive one of the smart khaki Mitsubishi work suits the company had issued its earlier‑mobilized students, she had to make do with her school’s designated war labor outfit instead—her Kenjo uniform blouse with “KENJO”‑emblazoned armband, a Rising Sun headband, and a pair of monpe. She was particularly attached to the latter item of clothing, which she had fashioned from a set of pajamas her father had had tailor‑made at a fancy Tokyo department store before the war. The expensive fabric’s bold—bordering on gaudy—parti‑color pattern of black, white, and light blue stripes was a reflection, in a sense, of its previous wearer’s personality, and it was a favorable contrast with the khaki or gray everyone else wore at the plant.

Masako made it to Ōhashi on time, as usual, for the plant’s daily chōrei morning assembly. At 0748, warning alert sirens began to sound while she was formed up in ranks with the other workers to listen to someone’s speech or perhaps to sing patriotic songs. As this less urgent of the two varieties of air defense alarms was always ignored at the plant as a rule, the assembly was still in formation when, two minutes later, the sirens sounded an air raid alert. Unlike the warning alert, this alarm could not be ignored—at least not legally; the workers broke ranks and evacuated in orderly fashion to company shelters in the hills about five hundred meters east of the plant, where they would remain until the all clear was sounded.

In almost all respects, Masako—true to her breeding—was the very model of a modest and gracious ojōsan. Still, because she was the proud daughter of a VIP, it was not beyond her to brag from time to time about her beloved, doting, and very important father. On the way back to her workstation after the 0830 all clear, Masako indulged this innocent conceit by regaling some of her Kenjo coworkers with a claim about her father’s apparently magical ability to protect himself and his family from American bombs. According to her, the Ishidas had escaped unscathed countless raids on Tokyo—including a huge one in March that had burned her father’s workplace to the ground. But the clincher of the “magically lucky” story was in its punch line: If her father’s scheduled posting to Hiroshima had not ended up being canceled by the Ministry of Justice the year before, Masako and her father would have been living in the middle of the city when it was destroyed by the American’s new‑type bomb three days earlier. Masako’s friends agreed that this was indeed luck bordering on the supernatural, and the girls chattered happily on their way back to what they probably expected would be another slow day of late‑war doldrums at the Ōhashi plant.

*

Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works Mori-machi

2.2 kilometers northwest of Nigiwai Bridge

*

Kiridōshi Michiko was late for work again—and this morning by over an hour. Although this was a not‑infrequent occurrence during her tenure as a Mitsubishi employee, she had never received so much as a sharp word from her supervisor over these infractions. But today, at least, she could legitimately blame her lateness on unforeseen circumstances beyond her control: Her overcrowded streetcar had jumped its rails, as it was wont to do from time to time, while attempting to negotiate the big turn the Number One Line took on its approach to the Dejima stop. As a result, she had had to walk the last two kilometers of the way to work—a trek that was, in turn, disrupted by her having to shelter in place during the morning’s air raid alert.

In this slow season at the plant, any out‑of‑the‑ordinary event that disrupted the day‑to‑day monotony was always fodder for factory‑floor gossip among the chatty girls of the parts‑polishing work team. When Michiko finally strolled onto the floor to take a seat at her worktable, she was immediately informed that she had missed an interesting sight that morning: A dashing, high‑ranking Kempeitai officer on horseback had posted himself by the main entrance to the plant, exhorting the day shift workers passing by to “fight until the end, even if you are a girl. Kill at least one enemy soldier before you die!”

Never a fan of this kind of rhetoric—with which she and the rest of the country had been bombarded for years—Michiko inwardly bristled at the anecdote before the running dialogue changed tack to rumors about the new‑type bomb the Americans had just dropped on Hiroshima. Michiko reported reading in the newspaper that people wearing white clothes had survived the blast. Another girl said she heard that they would be all right as long as they were not directly exposed to the flash of intense light from the bomb, so if that happened while they were at work, their factory building would probably protect them. Both of these theories were, in fact, at least partially correct; however, the new‑type‑bomb threat they did not yet know about—and against which the flimsy sheet metal and asbestos roof of their building would offer no protection whatsover—was the genetic‑material‑destroying shower of gamma rays and neutrons the weapon would release at the instant of its detonation.

As the stream of lively chitchat bounced to the next topic, Michiko gradually tuned it out and settled into her work: what was looking to be yet another boring morning of polishing and repolishing already finished and gleaming torpedo parts. Lunch break—which she would share, as usual, with her best buddy, Honda Sawa—could not come soon enough.

*

Junshin Girls’ School Ieno-machi

4.4 kilometers north of Nigiwai Bridge

*

Sister Itonaga Yoshi, like the other novices in the Junshin order, was an early riser. And this morning, she had already been up and about when the Fat Man strike force crews were still performing their pre‑mission aircraft checks on the Tinian flight line.

First, she had attended Matins prayers in the school chapel, then helped her novice colleagues prepare breakfast for six‑hundred‑odd diners—a task that had to be accomplished by the time Junshin’s students returned to campus from their daily morning mass at Urakami Cathedral. The students would take their meal in their respective homeroom classrooms, while the Sisters and novices would eat in their designated dining hall.

After breakfast, Mother Ezumi rose to address the room, as she did most mornings. But today, she had something special to talk about: her concerns over newspaper reports she had seen regarding a new‑type bomb the Americans had used to destroy Hiroshima. As there was a danger that the Americans might use one of these on Nagasaki, she wanted to keep as many of Junshin’s students as possible away from the city. Although the war effort could not spare the second‑, third‑, and fourth‑year girls working across the street at Ōhashi or at any of the other nearby Mitsubishi facilities where they toiled, there was no reason for the first‑year girls to be in the open and exposed every day, working on the athletic ground truck patches. Toward this end, starting today, she was going to order the first‑year commuters to stay home until further notice.

As for the first‑year boarders, Mother Ezumi wanted six of the younger Sisters to march them to a privately owned pine forest deep in the mountains in Mitsuyama, 4.4 kilometers northwest of the campus. An illustrious old kakure Kirishitan family—the Takamis— was letting Junshin use this land to collect pine sap for donation to government authorities, after which it would be distilled into fuel for warplanes. This was a very common patriotic project for volunteer laborers in late‑war Japan—especially among those either too old or too young to perform more demanding and exacting full‑time war plant work.

Although the “fuel” resulting from this collection‑and‑distillation process was poor in quality and tended to rapidly clog precious aircraft engines, it was increasingly relied upon by Japanese military aviation, which was now almost literally flying on fumes since the near‑complete strangulation of its overseas petroleum supply routes by the Allied blockade. And poor, engine‑damaging quality or not, the ersatz aviation fuel had to work only once to get a kamikaze plane up and away to hit one of the enemy warships now lazing about in the offing around the Home Islands, often close enough to be spotted from shore with the naked eye.

The new‑type‑bomb threat they did not yet know about…was the genetic‑material‑destroying shower of gamma rays and neutrons the weapon would release at the instant of its detonation.

After Mother Ezumi read off their names, the Sisters in the pine sap detail were sent on their way to load a wheelbarrow up with tapping implements and buckets, collect their student charges, and march off to Mitsuyama. Mother Ezumi then called out the names of four other Sisters who would remain on the campus with the junior novices as a faculty skeleton crew, with the former attending to school administration and the latter engaged in their customary truck patch tilling.

The other Sisters and senior novices—including Sister Yoshi—would go out on their usual factory chaperone duties with their student groups after the dismissal of the chōrei assembly. The five‑hundred‑or‑so‑strong Ōhashi detachment was supervised by Sister Christina Tagawa Tadako, and it was always a stirring sight—and sound—when the popular young Sister marched her girls through the school gate and across the Nagayo Road to their workplace, her bell‑like voice ringing high and clear over everyone else’s as the group sang some patriotic ballad or another.

Although the much smaller Michino’o/Togitsu metal foundry detachments could not compete with the Ōhashi unit in terms of sheer noise and numbers, these girls were in high spirits this fine and yet‑too‑hot hot morning. Today it was Sister Yoshi’s turn to escort them to their respective work floors. To enjoy this pleasant weather while it lasted, Sister Yoshi decided to forgo the usual dusty Urakami Valley main drag, the Togitsu Road, and instead head the group north along back streets and bucolic farm lanes to reach the foundries.

Back at the Junshin campus, the junior novices were still cleaning up after breakfast when sirens for a warning alert—quickly upgraded to an air raid alert—began echoing throughout the valley. Mother Ezumi, as she always did upon hearing air raid alarms, rushed to secure Junshin’s most sacred icon—a crucifix bestowed upon the order by Bishop Hayasaka. Once she took this down from her office wall, she cradled the precious item while assuming a crouch in a smaller slit trench beside the main building entrance. As per Junshin SOP, everyone else made for the larger trenches on the school’s athletic ground. There, Sister Hatanaka Yoshino, one of the novices, watched as Sister Clara—the order’s normally drill‑sergeant‑strict novitiate mistress— mumbled prayers and nervously thumbed her rosary.

With the morning’s drama apparently coming to an end with the 0830 all clear, the campus returned to its normal workaday routine. In the dining hall, the novices finished their interrupted breakfast cleanup, then headed out to the truck patches for another day of pulling radishes and weeds. In her office, Mother Ezumi returned the Founder’s Crucifix to its spot of honor on the wall—right next to the Kempeitai‑imposed kamidana installation; then she went back to the politically tricky business of running a Catholic parochial school in a Shintō country at war with—and more recently being bombed by—other Christians.

*

Fukuro-machi

One hundred twenty meters north of Nigiwai Bridge

*

Tateno Sueko woke up at her usual 0630. After participating in the semi‑mandatory daily morning ritual of radio gymnastics with the other members of the Fukuro‑machi neighborhood association, she marched off with her volunteer work team to begin another day of drudgery at the shelter‑digging site in Togiya‑machi.

Work had been underway for less than an hour when the 0748 warning alert sounded. At this signal, Sueko and the other underage members of the work team took shelter in the same hole they were helping to dig. Two minutes later, they were joined by their adult colleagues. Work resumed after the 0830 all clear, and Sueko returned to her regular slog of toting excavated soil to the sandbag‑filling team on the edge of the worksite.

*

Shimonishiyama-machi

1.4 kilometers from Nigiwai Bridge

*

On a normal day in their second‑story boarding room, the Gunge brothers would have enjoyed only a few minutes of each other’s fully conscious company in the brief time window they had together. But this morning, an air raid alert had sounded just as Yoshio was about to leave, so he was able to spend some unscheduled and rare downtime with his younger brother.

The brothers leisurely chatted for the next forty minutes, until the all clear sounded at 0830. At this, Yoshio set off to begin his half‑kilometer walk to the Suwa Shrine streetcar stop while Norio watched from a window to give his brother his customary wave at the front gate. When Yoshio was still a few steps from reaching the street, he stopped in his tracks, turned around, and called up to his brother.

“Hey, I forgot my fountain pen….Could you bring it down for me?”

Ever the obedient younger brother, Norio did as requested and handed over the pen.

When Yoshio reached the gate, he turned around and, smiling warmly, gave his brother one final wave.

__________________________________

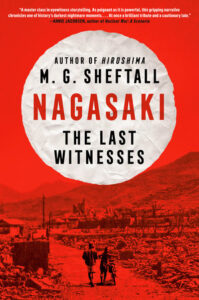

From Nagasaki: The Last Witnesses by M.G. Sheftall. Copyright © 2025 by M.G. Sheftall. Published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

M.G. Sheftall

M.G. Sheftall has lived in Japan since 1987. He has a PhD in international relations/modern Japanese history awarded by Waseda University in Tokyo, which is the most highly regarded private university in Japan. Since 2001, he has been a professor of modern Japanese cultural history and communication at the Faculty of Informatics of Shizuoka University, which is an institution in the Japanese national university system. Sheftall is married, with two adult sons, and makes his home in Hamamatsu, Japan.