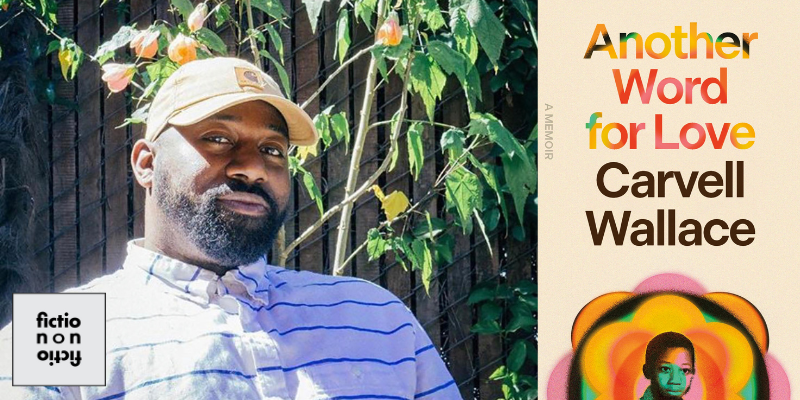

Carvell Wallace on Love, Survival, and Endings

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Writer and podcaster Carvell Wallace joins co-hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to discuss finding his way to the understanding that life is lived on a continuum and is not made up of neat endings and beginnings. He talks about how his childhood experiences with poverty, housing insecurity, and a frustrated creative genius of a single mother prepared him to understand the world. Wallace also discusses his expansive, generous approach to writing about both people he knows and loves and those he’s profiling as a journalist. He reads from his new memoir Another Word for Love.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: That late passage that we were just talking about, and that you read from, refers back to an image in your life from earlier in the book, when your mother made you walk through a cloud of fog to get to school. There’s a suggestion there and in other places in the book, that the experience of your childhood, of being a young Black man in America, helped prepare you for this concept of facing endings. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Carvell Wallace: Yeah, I don’t know if I agree with that, actually. I don’t know if I agree that my experiences as a Black man in America prepared me for that in any real way. I think it’s more like maybe my experiences with poverty helped support some of that, and certainly engagement with violence, which is and isn’t racialized in America, can be and cannot be – sort of depends – but I also, again, think that I got lucky enough to travel to Southeast Asia and go into monasteries where people…

You know, one time my travel partner and I, this is like ’99, we were in a small town off the coast of Bangkok and on an island – I think it was Koh Sichang, if I’m not mistaken – and there was a monastery on the island that was built into the side of a mountain. We went to visit because we had heard that, at the time in ’99, there weren’t a lot of tourists there, but we heard that there was a monastery there you could visit. And so we ran into another tourist who was from Taiwan, and he was like, “Oh, I’ve been waiting to visit this thing too.” So we go, and we meet with these monks and nuns, and they show us around. They don’t speak a lot of English, but they’re just kind of giving us a tour, and at one point we walked into a dark cave where there was meditation, and it was dark, and they lit a candle, and there was a human skeleton lying on a platform. They were explaining to us what this was, but we didn’t fully get it, because we had a language barrier, but then slowly it dawned on us that what was happening is this was a place that people come to meditate on impermanence. The body was one of the sisters who had lived there but had passed on.

The reason I bring that up is because that’s the image I always think of when I think about preparing for endings. It’s what I saw in that cave, in that moment, in addition to other readings that I had done. I’m pointing to this book that I got in Thailand, What the Buddha Taught, that was meditations on ways of understanding that the ending of things is real, and our inability to address it makes it really hard for us to operate in the regular world as it is, and it puts us in fear and resentment and conflict and fight, etc, etc. And so to be present with the ending, the potential ending of things, actually it frees you up to love and be loved, etc. That’s why I don’t think of that necessarily as the result of a racialized experience.

I think some aspects of my life allowed me to grasp that, but I also think that I learned about it from other people who did not have the same racialized experience that I had. So I think it’s a human truth, and I think it’s just a matter of have you been exposed to that truth, and are you willing to explore that as a possibility and perhaps see the power of it?

WT: That’s the thing that McPherson would have – our teacher we mentioned at the beginning of the podcast is James Alan McPherson, who taught us at Iowa, who both Sugi and I studied with – but that’s the kind of thing that he would have talked about.

CW: Yeah. I think it’s kind of a universal thing. I think it defies class, culture, race, gender, sexual identity. I think that it’s an aspect of the human experience.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: You and your mother were at times homeless; you had difficulty finding food. You write, “I had just turned eight when my mother gave me up for a second time.” And that her anger reminded you of a shark. But you also write, “[T]he feeling of hurtling along is itself the feeling of home, a human truth the size of the universe, the size of my mother and me in a motel with no future to be certain of.” Could you introduce her to our listeners and describe what she was like?

CW: Yeah, I think she was a frustrated creative genius. I think she was a person who was endowed with advanced creative capacity and lived a life in which, for a wide variety of reasons, she was unable to pursue those when she was born, the body she was born in, what happened to her life after she was born. She was a single mom. She got pregnant at 19. She didn’t have a college education. She had to figure out how to keep the lights on for her and her son. That was a difficult task; it didn’t always work out. She was incredibly intelligent. She probably had some mental health disorders that made it hard for her to function, and when I think of her, I think of a person having a life that was actually meant to be elsewhere. I think of the phrase, “Life is elsewhere.” In fact, isn’t that a book title? Milan Kundera, am I making that up? Maybe I made that up.

WT: It sounds familiar to me.

CW: I don’t know, but the phrase “life is elsewhere” is something that I always think about when I think of her, and so I think that there was a grief, a depression, a frustration, a sadness that came with being confined to a situation and a place and a body and a world and a culture and a civilization that is not, perhaps, your own, and that you can’t get to your own because of your here. I think that’s the way I remember her.

She was incredibly loving, and I think she was really supportive of me as an artist, which is not something that other people in my life were. I think she understood that if I didn’t pursue my creative voice that I would be frustrated and perhaps self-destructive, maybe the way that she was. So when other people were like, “Maybe you should get a real job,” she was like, “No, this is what you have to do.” You know, “Here’s an after school program, here’s a theater thing for you to go to.” She saw it, and so I really appreciate that in her.

I think that she had a lot of pride in herself and in me. She was really visually motivated. She understood beauty, and she cared very deeply about beauty. And I watched her beauty rituals from the time I was a little child, and it taught me a lot about how to care for things and create things. She did this with her dress and her hair and her makeup, and she took it very seriously. And then later, as she grew – I write about this in the book – she fell in love with aspects of the natural world, gemstones, and also, toward the end of her life, she became very, quite preoccupied with mysticism and the occult and. I didn’t write about that a lot in the book, I think that will come up a little bit more in the next book that I’m working on. But she was looking for things that were deeper and held space better than what she saw in the world around her.

So I remember her as a beautiful person, a frustrated person, a person struggling. A lot of what motivates me to keep going when I’m afraid is that I’m carrying the ball that she handed off to me. I have a responsibility to both of us, you know, she and I were a team. When you’re a single child and you have a single mom and you’re struggling with money and stuff, you become a team. It’s like you and mom versus the world, and we had some aspects of that, even though we were apart for years. So I still feel that connection, like I’m out here doing stuff and pursuing avenues and exploring aspects of existence in the universe, and beauty and creation that she imputes me to explore.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Vianna O’Hara.

*

Others:

Life is Elsewhere by Milan Kundera • Marilynne Robinson • Easy Rider • “Remembering Hollywood’s Hays Code, 40 Years On” | All Things Considered, NPR | August 8, 2008 • James Alan McPherson

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.