Capitalism Has Distorted Desire in the #MeToo Era

A Brief History of Literary Seduction

Needless to say: it wasn’t meant to be like this. Fifty years after the Summer of Love we have arrived at an impasse in our sexual culture that few would have foreseen a decade ago, let alone during that fervid season of taboo-busting and inhibition-shedding now remembered as the sexual revolution. Today the talk is of sexual recession, not sexual revolution. The permissiveness of yesteryear is not simply dwindling; it is subject to revisionist scrutiny.

Events have taken their toll. Impassioned debates about consent, especially on college campuses, co-exist with the rise of ever more gruesome sexual subcultures (pickup artists, incels). Algorithmic dating has displaced whatever we did before the gods gave us Tinder. Since the Weinstein revelations we have lived by reference to the enveloping #MeToo moment, that outburst of rage in October 2017 that has stayed with us, a permanent winter of sexual discontent.

How did we get here?

I’ve spent the last five years or so reading, thinking, and writing about the history of seduction. The history of seduction is the history of those strange and powerful things, seduction narratives. Those narratives in turn are debates about our essential nature: are we rational or passionate beings? Consider Pride and Prejudice. Lydia is described throughout as being the antithesis of her calm, rational elder sisters. She is “self-willed and careless” with “high animal spirits.” When, inevitably, she runs away from Brighton with her lover Wickham, Elizabeth reflects that the couple’s “passions were stronger than their virtue.”

Most people will have heard of “free love” and “sexual liberation” without interrogating what those terms actually mean.

Kitty despairs of her own prospects now that her sister has behaved so badly. Will she ever get to go to Brighton herself? “’You go to Brighton.’” Her father rages. ‘I would not trust you so near it as Eastbourne for fifty pounds!’” And then Mr. Bennet offers the moral of the story: “’You are never to stir out of doors till you can prove that you have spent ten minutes of every day in a rational manner.’” His daughters will be cured of their dangerous passions by the corrective of reason.

Reason is not simply the cure but the path to freedom. Rebelling against the cult of sensibility in her own era, Mary Wollstonecraft insisted on her right to pursue her “rational desires.” In her pedagogical writings (Wollstonecraft was a teacher for much of her life) she argued for the necessity of a proper education for women—conducted, of course, under “the sober steady eye of reason”—in order to prepare them for sexual freedom.

Women risked seduction, abandonment, and ruin, Wollstonecraft believed, because they were trapped within a system more “anxious to make [women] alluring mistresses than rational wives.” This system had made them mere “creatures of sensation”; an education would make them rational and so set them free.

*

Virginia Woolf observed of Wollstonecraft that because her “originality has become our commonplace” it can be hard to understand how radical her positions then were. By the standards of our own time, she can sound unambitious—even quite conservative. Whatever these limitations, Wollstonecraft remains relevant to us because she was actually doing the intellectual work required to answer the question many people today don’t ask at all: what is sexual freedom?

Most people will have heard of “free love” and “sexual liberation” without interrogating what those terms actually mean. This is a shame because those terms have origins that help explain where we are today.

The most famous advocate of free love in Wollstonecraft’s time was her husband, the philosopher William Godwin, infamous in his day for declaring that “marriage is an affair of property, and the worst of all properties.” The implication was clear: the abolition of property would have implications for the status of marriage and vice versa. This was a basic assumption in socialist thought. You can trace it from Godwin, through to Charles Fourier, Friedrich Engels, August Bebel, William Morris, and Alexandra Kollontai, all the way up to Herbert Marcuse and the intellectuals of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s.

What all these thinkers held in common was that property arrangements had distorted sexual relations. Once property had been redistributed (or collectivized or abolished, etc.) then men and women would be liberated from the forces confusing their sexual choices. They would have arrived at a state of pure reason. They would be free.

The consumerist logic that underwrites much of our contemporary sexual culture is profoundly dehumanizing.

It is possible that we’re now living with the consequences of one revolution that happened and one that did not. The socialist revolution never came, but the sexual revolution did. Socialism lost out to capitalism; collectivism lost out to individualism. A certain kind of sexual rationalism did triumph—but it was the logic of the market.

Sexuality was not liberated, it was liberalized. How else are we to understand a world where sociologists exhort us to accumulate erotic capital, where pickup artists boast of inventing an “algorithm for getting women,” and where dating apps present us to each other in rows of rectangular mugshots, stacked up on top of one another like cans of soup?

This is not a plea for a radical reformation of sexual attitudes along socialist lines. The history of such attempts is not a pretty one. State-led initiatives in the Soviet Union and Cambodia led to suffering and resistance. Voluntary movements towards collective sexuality have existed in the United States and elsewhere. Under the aegis of their Smash Monogamy campaign, the Weathermen scheduled obligatory orgies to help strip their members of their residual attachment to bourgeois norms. The experiment was short-lived. Group sex mandated by wild-eyed Maoist guerrillas is not most people’s idea of sexual freedom.

It is rather a suggestion that we recognize the limits of a purely rational approach to sexuality and desire. Reason has always existed in symbiosis with the passions. “The impulse of the senses, passions, if you will,” Wollstonecraft wrote, “and the conclusions of reason, draw men together.” We need both. The consumerist logic that underwrites much of our contemporary sexual culture is profoundly dehumanizing. #MeToo is many things, but it is surely evidence of a major breakdown in our capacity to empathize, to relate, to feel.

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy’s great novel of seduction, sexual hypocrisy, and doomed love, Angel Clare reflects on why he can’t bring himself to seduce and discard the titular heroine: “Tess was no insignificant creature to toy with and dismiss; but a woman living her precious life—a life which, to herself who endured or enjoyed it, possessed as great a dimension as the life of the mightiest to himself.”

The question for us is whether we can rediscover the precious lives of others in an age where the median number of characters in a Tinder message sent from a man to a woman is twelve.

__________________________________

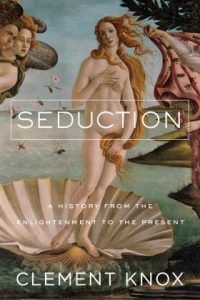

Clement Knox’s Seduction is available from Pegasus Books.

Clement Knox

Clement Knox has a B.A. in Modern History from the University of Oxford and an M.A. in International Relations and Economics from Johns Hopkins University. He currently lives in London, where he is a nonfiction buyer for Waterstones. His book Seduction is available from Pegasus Books.