Can You Measure the Happiness of Your Favorite Story?

On Happy Plots, Machines and Literature

I don’t believe that only sorrow

and misery can be written.

Happiness, too, can be precise

–from “Happiness Writes White” by Edward Hirsch

*

I don’t believe that when Edward Hirsch wrote “Happiness, too, can be precise” he was thinking that it could be depicted with a number, though the poem does insist that happiness can be precisely described. We can represent happiness with our language. Words can capture joy.

Emily Dickinson plays with the idea of expressing and quantifying emotion in “It’s all I have to bring today” as well. The poem playfully takes an expression of love, one that encompasses all that the speaker adores—heart, fields, meadows, bees—and asks for its sum.

I should not have been surprised to learn that just a few years back, researchers devised a way to quantify happiness via language as well, and yet I was. The creators of the Hedonometer, an instrument for measuring happiness, determine the happiness of a text (anything from a novel to a collection of tweets) based on its words and give it a happiness score. The results—the societal happiness the system calculates by evaluating a day’s worth of tweets, for example—correspond to patterns found in Gallup well-being polls.

To calculate the happiness of a text, the researchers first determined how happy individual words are. They asked 50 people to score each of about 10,000 words for happiness on a scale from 1 to 9 and then averaged the scores to produce a final value. The word “laughter” is the happiest word, earning a score: of 8.5. “terrorist” received the lowest mark, 1.3. In between, one finds words like “deserve” (6.4), “doorway” (5.65), “alcohol” (5.2), “bias” (4.31) and “aggressive” (3.8). The word “love” lies just below “happiness” and above “happy” with a score of 8.42. The word “happiness” itself received a score of 8.44.

I downloaded the dataset, which the authors share online, and began to ask more questions. Which word is happier, man (5.9) or woman (6.84)? Breakfast (6.86) or lunch (7.42)? Pretty (7.32) or kind (7.24)? Did I agree or not, I asked myself.

When I ask myself how happy the word millionaire is, I stare blankly at my screen.

I did not know the 50 personal stories the happiness scorers brought to their evaluations—the child who’d just died, the friend who’d just married, the lover who’d just walked out—only the average score, the measure that reflects the diversity of experiences the individuals had, whatever it was that caused this set of 50 strangers to mostly agree about how happy the word “table” is (5.32, with a standard deviation of .68) and to differ on words like millionaire (7.62, with a standard deviation of over 2). When I ask myself how happy the word millionaire is, I stare blankly at my screen.

Hirsch claims we can capture happiness with words, and I believe he is right. I love “Happiness Writes White”; when I read it, I feel happiness, but I also believe the emotional connection I make is a result of Hirsch’s skill as a poet. My happiness is not evoked by the individual words, but the idea that we have the power to collect the beauty that surrounds us, to hold it in our hands, to make and to share the joy in what we have been given. In just a few lines, Hirsch invites me inside his own body, where I encounter his joy and am reminded that it resembles things I, too, know but may have forgotten.

When I think of happiness, it usually takes the form of a narrative, an event or interaction that has evoked the feeling, and I was fascinated and somewhat baffled by the idea of measuring the emotion with word scores. “While the plot captures the mechanics of a narrative and the structure encodes their delivery, in the present work we examine the emotional arc that is invoked through the words used,” the researchers write.

Until I read the study, I’d never thought about the emotional arc of a novel in terms of happiness or the happiness quotient of the words used, but the researchers had not only measured happiness and how it changed over the course of a work with word scores, but found that the emotional arcs they captured often fell into one of six common shapes (“Rags-to-riches” or “Cinderella” stories, for example), an idea that Kurt Vonnegut famously put forward in his rejected master’s thesis for the University of Chicago. Vonnegut thought that these shapes could be fed into a computer, and the researchers agree, noting that one could, among other things, use these emotional arcs to aid “in the generation of compelling stories.”

Had I been blind to the obvious? Was happiness key to a compelling narrative? What is the role of happiness in narrative and the process of its construction? I asked a few writers for their thoughts.

“I find the shape of stories to be very interesting, considering I spend a lot of time analyzing them,” San Francisco-based author Jilanne Hoffmann notes. “Happiness, on the other hand, is not so much on my radar.”

Daphne Kalotay expressed a similar sentiment, “I don’t think about happiness per se when I write, but I have thought of it after having written—as in realizing I didn’t allow for a happy-ish ending or for a character to have a chance at happiness.”

When I asked Josh Mohr if he thought about happiness when he wrote, he replied, “I don’t consciously think about ANYTHING while I write. My goal is to try and empower my characters and mute my authorial consciousness—so they are in charge of a novel’s dominant action.” He adds that when he reads, “I do notice . . . when a certain chapter or passage makes me happy. Now, that doesn’t mean the passage itself is Happy; however, there’s something about the language, or an image, or an interaction that elicits that type of emotional response in me.”

Laurel Leigh was the only one of the four writers I asked who said that she was explicitly conscious of happiness as she worked on her fiction:

My idea of happiness desired/lost translates into characters who are ultimately undone by their own agency . . . The more complicated the character, the more awareness they have about the potential outcome of their choice in terms of it affecting their happiness or desire. It’s been a map for my Shoeless stories, where I can say that the characters tend to fall more gracefully than they rise, although how far they rise or fall varies and how much grace they display varies. Figuring out the corresponding plot points and what results from a pivotal choice usually gives me the beginning and ending of the story, and then I have to suffer through the middle to figure out how to play out the larger scenario.

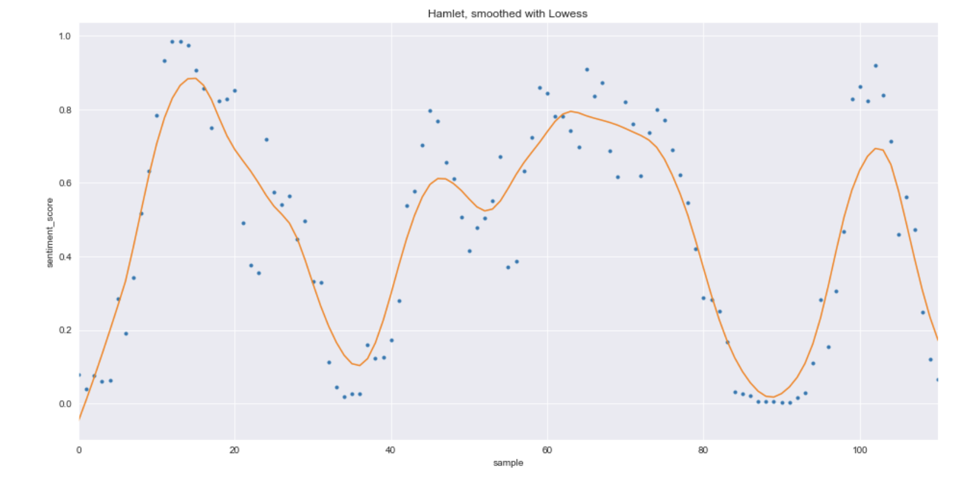

I took a look at some of the happiness arcs generated by the Hedonometer. Here, for example, is Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

Screenshot from: https://github.com/andyreagan/core-stories/blob/master/src/vis/shakespeare-plays.ipynb

Screenshot from: https://github.com/andyreagan/core-stories/blob/master/src/vis/shakespeare-plays.ipynb

It seemed reasonable that the happiness would fall. Pretty much everyone dies at the end of the play, after all. Still, I thought I would see what happened if I asked a different machine learning system to evaluate the play.

I found a blog post by Daniel Kuster, Ph.D., another researcher who’d experimented with finding patterns in narrative. His story-arc technique uses sentiment analysis, scores that reflect how positive or negative a passage is. Dr. Kuster’s conclusion was not unlike that of the Hedonometer team, only he was looking specifically at a handful of Disney screenplays: “Basically, the last half of these Disney scripts are very much like Vonnegut’s ‘man-in-a-hole’ story shape,” he writes, though he also notes that “the beginning half can vary quite a lot.”

In an email, Dr. Kuster noted that the Disney screenplays were simple stories, but that for more sophisticated stories or nonfiction, his sentiment-based model might not reveal the shape as well.

I ran Hamlet through Dr. Kuster’s system and got this arc:

Story arc for Hamlet using https://github.com/IndicoDataSolutions/plotlines

Story arc for Hamlet using https://github.com/IndicoDataSolutions/plotlines

It is foolish to compare the two graph plots, they measure different qualities of the text in different ways, and yet, I was startled at first because the two arcs—one based on happiness scores, the other on sentiment scores—are so different. Without realizing it, I’d assumed that the two models would arrive at roughly the same conclusion.

“And even once you had the algorithmic bits worked out, validating the results can be tricky when human interpretations differ,” Dr. Kuster writes in his blog post. Literature does not have a single answer; no two people will read a story in exactly the same way.

Shakespeare is dead and cannot weigh in with his thoughts about the story arc of Hamlet, but Vonnegut discusses it in A Man Without a Country.

“The question is, does this system I’ve devised help us in the evaluation of literature? Perhaps a real masterpiece cannot be crucified on a cross of this design. How about Hamlet?” Vonnegut wonders. “It’s a pretty good piece of work I’d say…”

Vonnegut considers the ghost. “We don’t know whether this thing was really Hamlet’s father or if it was good news or bad news. And neither does Hamlet.” Hamlet journeys from one ambiguously good or bad moment to another until he fights in a duel and is killed. “Well, did he go to heaven or did he go to hell? Quite a difference . . . I don’t think Shakespeare believed in a heaven or hell any more than I do.”

“But there is a reason we recognize Hamlet as a masterpiece,” Vonnegut concludes, “it’s that Shakespeare told us the truth, and people so rarely tell us the truth in this rise and fall here. The truth is, we know so little about life, we don’t really know what the good news is and what the bad news is.”

The story arc Vonnegut draws for Hamlet is this, no arc at all:

From: A Man Without A Country (Random House; 2005) by Kurt Vonnegut

From: A Man Without A Country (Random House; 2005) by Kurt Vonnegut

Special thanks to Dr. Reagan and Dr. Kuster for sharing their work, code, and thoughts with me.

Kirsten Menger-Anderson

Kirsten Menger-Anderson is a writer and researcher based in San Francisco. She is the author of Doctor Olaf van Schuler's Brain.