Can We Really Claim That Civilization is on the Steady Path of Progress?

Samuel Miller McDonald on Black Liberation, the Abolition of Slavery,

and the Myth of Progress

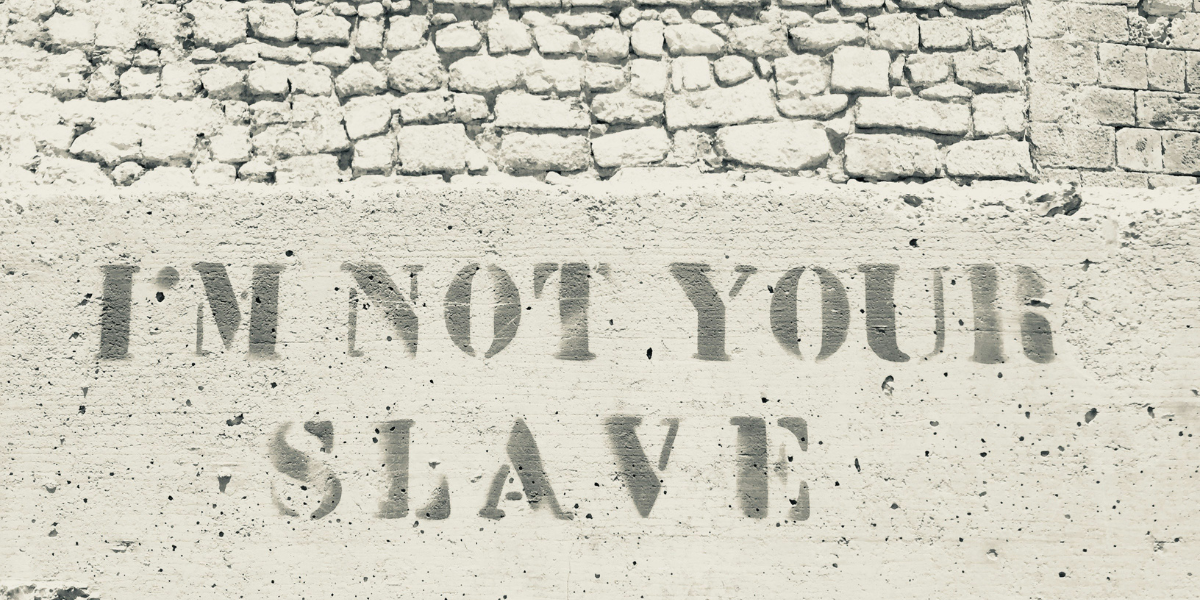

One of the most common contemporary arguments for the idea of human progress is in the arena of social justice: the belief that there have been steady improvements in fairness, equality, and opportunity for more people. Social justice narratives begin to reveal why a lineage of “progress” is used instead of simply pointing to a positive change. Many claim that with the abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of women, and many other new laws like civil rights legislation and changing gender norms, there has been great progress.

Today, this kind of progress is most often depicted by representational politics, the idea that the representation of a minority group or of women in positions of power and privilege are indicators of progress. But is progress really the right frame to apply to these changes? Again, that a good thing happens does not necessarily indicate a pattern of progress.

In 1964, Malcolm X said: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even pulled the knife out, much less try and heal the wound. They won’t even admit the knife is there.”

The abolition of slavery cannot be counted as evidence of a long moral arc, a momentum of human history, indicating a pattern of progress.

Consider for a moment this quote and what it means with regard to the Atlantic slave trade. Huge numbers of African people were living out their lives, often in peace and equanimity, when out of nowhere, armed men appeared. These men kidnapped them and put them on ships where they either died or suffered extreme fear and illness. They then arrived in an alien land in harsh conditions, and worked brutally for long hours under the constant threat of corporal or capital punishment doled out by masters who feared no consequences for their violence.

Meanwhile, the slaves’ families were broken up, left impoverished, and in many cases their cultures, languages, and land were soon imperiled by invading colonial forces. Even if the severity of this mayhem is grudgingly reduced—after great public agitation and a civil war—given the starting point in Africa prior to enslavement, we cannot reasonably call that “progress.”

The abolition of slavery cannot be counted as evidence of a long moral arc, a momentum of human history, indicating a pattern of progress. Those who were captured lived a far different trajectory from the European one they were thrust into: they suffered a sudden, history-breaking apocalypse, the traumas of which their descendants still endure, with many trapped in the limbo of a dystopian system.

Even if certain conditions have changed for the better, their enslavement lasted 246 years, while their relatively emancipated condition (such as it is) has lasted for only 156. To return to Malcolm X on the “freeing” of African Americans: “How can you thank a man for giving you what’s already yours? How then can you thank him for giving you only part of what’s already yours? You haven’t even made progress, if what’s being given to you, you should have had already.”

For the vast majority of human history, slavery was nonexistent or rare, sporadic rather than institutionalized. Then it became commonplace and inescapable.

And for many Black people in America, conditions have only changed to some extent. The Atlantic slave trade was evil, and a world in which it is no more is a world improved; but, its abolition is not evidence supporting a grand narrative of historical progress. There are a few reasons for this.

One is that for all or most of the people ensnared in the slave trade, their lives were undoubtedly better before capture and their ancestors’ lives were better for generations upon generations prior to enslavement. To place people in the worst possible calamity and then take some of that evil away, as mentioned, is not an example of progress.

In the same vein, slavery as an institution is an evil that, to our knowledge, is probably only five thousand or so years old. For the vast majority of human history, slavery was nonexistent or rare, sporadic rather than institutionalized. Then it became commonplace and inescapable. Returning to a situation in which slavery is rare, or even a situation in which slavery is totally abolished, is simply returning to a more natural state of being human, not advancing to some higher state from a primitive one.

But I should hasten to point out that we do not currently live in a condition in which slavery is rare or has been abolished. There are three times more enslaved people today in absolute numbers than there were at the height of the Atlantic slave trade—40 million people, or around one in every two hundred, are enslaved (this is not including “wage slavery,” in which people are forced to participate in a labor market for a pittance or even for wages that are then stolen, which is much more widespread).

As Kate Hodal writes for The Guardian, “There isn’t a single country that isn’t tainted by slavery,” with enslaved people still manufacturing clothes, growing food, and mining minerals used in technology, even in richer countries. The UK has an estimated thirteen thousand enslaved people. Even though there are prohibitions on slavery, the institution persists across the world.

The second reason is that progress narratives depend on an arc bending in a particular direction, which presumes the existence of a future end state. But there are no such stasis points in time: things change and rarely settle permanently. There’s no good reason to believe that slavery will remain “abolished” in the United States and Europe and elsewhere. There have been many times throughout history when slavery was suppressed, even abolished in part, for extended periods, and then resumed.

If market economies continue, there is little reason to assume they will not return to trade in indentured human beings.

The Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus in what is now Iran, likely diminished slave labor considerably for as much as two centuries before it returned for many centuries more. In the ancient Mauryan Empire in India, Ashoka may also have temporarily reduced slavery by abolishing slave trading, but this change too was not permanent.

There are many reasons to believe that some form of forced labor will return to many of the places where it has so recently (in historical terms) been abolished—as it was recently in the wake of Muammar Gaddafi’s overthrow in Libya—though it may not look like it did in the past, or may not be racialized in the same way.

This is because climate change and ecological collapse are very likely to cause political fragmentation that nullifies legal and cultural precedents like abolition, and bring about agrarian and manufacturing crises and scarcities in which people are forced into labor. If market economies continue, there is little reason to assume they will not return to trade in indentured human beings.

But what if we home in from the very large scale of all of human history to more recent times? What if we just look at progress in social justice within the scope of a period from the recent past to the present: have things generally been getting better?

About twice as many Black men are under state and federal criminal supervision—in prison, under probation—as were enslaved at the height of antebellum America.

The United States has by some way the highest incarceration rate and imprisoned population in the world, with 2.1 million prisoners. That is about 400,000 more than the next highest country, China (about 1.7 million), even though it has less than a quarter as many people (328 million to 1.4 billion). The proportion of Black Americans in the United States is one-fifth (13 percent) that of White Americans (64 percent), but Black people represent the same proportion of the prison population (about 40 percent)—meaning the incarceration rate of Black people is five times higher.

“More than half of all black men without a high-school diploma go to prison at some time in their lives,” writes Adam Gopnik for the New Yorker. “Mass incarceration on a scale almost unexampled in human history is a fundamental fact of our country today—perhaps the fundamental fact, as slavery was the fundamental fact of 1850.”

About twice as many Black men are under state and federal criminal supervision—in prison, under probation—as were enslaved at the height of antebellum America. Those prisons can be hellish. Forced unwaged or underwaged prison labor, sometimes in extreme, dangerous conditions like fighting wildfires, remains a stark reality for many.

“Prison inmates are picking fruits and vegetables at a rate not seen since Jim Crow,” reads one recent report on the practice of “leasing” convicted federal prisoners to do farm labor. Forcing people in chains to work in fields or at wildfires is not meaningfully different from, or morally superior to, nineteenth-century chattel slavery. Is this really progress?

A callous observer might reply, “Well, if they didn’t want to be forced to work in brutal conditions, they shouldn’t have committed a crime.” But the fact is that Black people are policed differently, sentenced differently, and imprisoned differently from non-Black Americans, who are also over-surveilled, over-incarcerated, and living in a virtual police state. The vast majority of inmates in local jails have not even been convicted, and only about half of inmates in prisons are there for violent crimes.

According to one study, Black men are sentenced to an average of 10 percent more time in prison than White men for committing the same crime. Though the rate of marijuana consumption among Black and White Americans is comparable, Black users are 3.7 times more likely to be arrested for possession. A recent study at Northwestern University found that White Americans vastly overestimate racial progress.

And it’s not just in the difference in treatment by the legal system: the fact is, the wealth gap between Black and White Americans has not shrunk in over half a century. Although the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a landmark policy change, rampant voter disenfranchisement remains a major problem among Black communities.

Social psychologist Jennifer A. Richeson wrote for The Atlantic, “Some essential civil rights have advanced, though unevenly, episodically, and usually only following great and contentious effort. But many areas never saw much progress, or what progress was made has been halted or even reversed.”

The representation of marginalized identities in power, business, or media is often hailed as indisputable proof of progress. But this representation does not yield improvements for most people who share those identities any more than having monarchs and emperors of a certain race or gender has improved conditions for workers and peasants of the same race and gender during history’s millennia of slavery, serfdom, and conscription. Such representation is more often used as a tactic for blocking egalitarian policies than for achieving them.

But even despite Obama’s presidency, the Promised Land remains out of reach for most. Or, in part, it remains out of reach because of Obama’s presidency.

Former President Barack Obama offers an illuminating illustration of this. President Obama has been one of the deftest wielders of progress narratives in modern history. It comes as no surprise that his 2020 autobiography is titled A Promised Land—the “Promised Land,” as this book will detail, is a millennia-old cliché representing one of the original progress narratives. In a way, Obama’s career perfectly represents the hollowness of representation politics and the cynical deployment of progress rhetoric.

Instead of widespread liberation for many, his own success stands in to embody progress: “[Obama] admits that his campaign deliberately ‘helped to construct’ this association in the public’s mind between the election of Barack Obama to the presidency and the fulfillment of America’s promise and the end to people’s troubles. The route to the ‘promised land’ was through his presidency.”

But even despite Obama’s presidency, the Promised Land remains out of reach for most. Or, in part, it remains out of reach because of Obama’s presidency: aside from the financiers his administration bailed out with trillions of taxpayer dollars, the top 1 percent of wealth holders who captured 95 percent of income gains under his administration (one of the largest transfers of wealth to the already-wealthy in history) and his own family, whom he enriched thirty-fold while in office, President Obama did not lead anyone to the Promised Land.

Far from Black people being liberated, conditions changed little for marginalized groups, and Obama’s administration even found opportunities to brutalize them. In 2015, Black Lives Matter protests erupted against police terrorism and a lack of racial progress during his administration. Obama’s response was the violent suppression both of Black Lives Matter protestors and primarily of Indigenous Water Protectors, who protested against the expansion of oil pipelines in Standing Rock land in North Dakota.

The aggregate wealth of Black Americans decreased under Obama’s administration. As Jacobin reports:

Between 2007 and 2016, the average wealth of the bottom 99 percent dropped by $4,500. Over the same period, the average wealth of the top 1 percent rose by $4.9 million. This drop hit the housing wealth of African Americans particularly hard. Outside of home equity, black wealth recovered its 2007 level by 2016. But average black home equity was still $16,700 lower. Much of this decline . . . can be laid at the feet of President Obama.

In a perhaps too on-the-nose example, Obama’s Presidential Center, currently under construction in Chicago, is set to displace a community of working-class Black people. Obama’s administration increased drone strikes tenfold in the Middle East, deported a record number of people, and constructed the border detention centers that would become infamous under his successor, President Trump.

A report by the Manhattan Institute (a “free market” think tank, to be sure) argues that Obama’s presidency failed to deliver any of the promised progress to Black Americans, stating, “During an era of growing black political influence, blacks as a group progressed at a slower rate than whites, and the black poor actually lost ground.”

It was Obama’s administration, as well, whose handling of the overthrow of Libya’s dictator led to slave markets being reopened there. Obama even dramatically increased fossil fuel exploitation and carbon emissions during his administration, and then bragged about it to a roomful of oil moguls.

__________________________________

From Progress: How One Idea Built Civilization and Now Threatens to Destroy It. Used with the permission of the publisher, St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 2025 by Samuel Miller McDonald.

Samuel Miller McDonald

SAMUEL MILLER MCDONALD is a geographer focusing on human-ecology, theory, and history. He holds a doctorate from Brasenose College, University of Oxford and degrees from Yale University and College of the Atlantic. He has written essays and analysis for The Nation, The Guardian, The New Republic, Current Affairs, Boston Review, and elsewhere, and has contributed interviews to BBC Ideas, VICE News Tonight, and various radio and podcast programs. Progress is his first book.