Can Speculative Short Fiction Really Work on TV?

On Black Mirror, Electric Dreams, and Her Body and Other Parties

We can really only handle our fictional dystopias in short-form; the world in 2018 is enough of a long-form dystopia for most of us. And the logic of a dystopian world doesn’t leave much room for any other type of story, since one factor all well-drawn dystopias share is a clear-sighted acknowledgment that the citizens inhabiting its world have lost whatever ability they had to determine the course of their lives. If the storyteller has done their job right, it would be unbearable for us to spend any more time in such a place. Soylent Green, Richard Fleischer’s 1973 film about a dystopian 2022 plagued by homelessness and starvation, ends with the protagonist being carted away, screaming in vain to anyone within earshot that the miracle product Soylent Green is people. What else is there to say?

Black Mirror, perhaps the most immediately popular work of speculative fiction in the last few years that doesn’t have “Star” in its title, thrives on the anthology format, producing seasons of television that function almost like short story collections. As the show has gone on, it’s hinted at connections between episodes, but for the most part each is a self-contained story about humanity and its relationship to a particular sort of technology—everything from mechanized bees to cameras that let you replay your memories to shibboleths of loved ones, recreated from their social media data. With Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams, Amazon has tried to enter the same space, using the short stories of Philip K. Dick as inspiration.

It’s instructive to look at where these two series fail and where they succeed at pulling off shorter-format stories in this vein. Black Mirror has long been dogged by criticism of the “what if phones but too much” variety (or, more recently, tweets mocking the supposed profundity of techno-paranoia). The worst episodes suffer from a sort of piercing didacticism and self-seriousness, borne from the single-mindedness with which Charlie Brooker commits to his vision for each episode—and the way it can often seem like Black Mirror is loudly telling you that yes, your phone might be bad.

Thankfully, the better episodes shake off this moralism to deliver genuinely good stories that aren’t nearly as reliant on gimmickry. Take this season’s “USS Callister,” which pulls off a sustained critique of nerd culture by depicting a Star Trek obsessive as a tyrannical, petty monster—in addition to being a genuinely fun story with a funny heist component. These episodes succeed because they’re good stories about people. They use technological MacGuffins to push characters together, rather than using them to reverse engineer a story in which the technology becomes alarming. In the worst cases, characters exist solely in relation to a piece of technology, as in Black Mirror’s VR-inspired episode, whose protagonist exists only to be scared by the virtual reality experience. Black Mirror’s more fleshed-out, compelling characters don’t know that they’re in a story about technology innovations and don’t act like it—they’re just acting like people. These episodes move just a hair past what we might expect the world to go.

From “USS Callister.”

From “USS Callister.”

With a couple of exceptions, Philip K Dick’s Electric Dreams mostly fails at recreating—or even really evoking—the anxiety, propulsion, and faint recognition that comes from reading a Philip K. Dick short story. In part, this may be because of the source material. The type of vertiginous, nail-scratching distrust of reality Dick’s best work imparts is difficult to capture on-screen. (The Blade Runner films, the gold standard for Dick adaptations, succeed in part because they center their existential paranoia on the humanity of the characters, rather than the nature of reality itself.) There is great cinematic speculative fiction, but the type of work Dick specialized in is hard to capture on-screen. His prose is rushed, his ideas splatter against the wall like fruit that’s alternately overripe and perfectly juicy. For every A Scanner Darkly, which hums along menacingly as it transmits the distinct feeling of being uncertain that you are where you are supposed to be or doing what you are supposed to do, there’s A Maze of Death, which has thought-provoking, bizarre twists and turns toward its conclusion, but which is perhaps too full of invented jargon and sentences about one character’s “undersized wife.” Dick’s worlds are frequently sketches, outlined in a way that’s okay in a short story but just doesn’t work on TV—at least not in Electric Dreams, where the production is too lush to be charmingly spare and evocative, not whole enough to create an entire world.

From “Crazy Diamond.”

From “Crazy Diamond.”

Another reason Electric Dreams feels so hollow is that its attempt to film what was then cutting-edge speculative fiction has run up against a coat of rust. Dick’s work—and, in particular, the short stories adapted for Electric Dreams, were prophetic at times, but were also very much of their time. The Steve Buscemi-starring episode, “Crazy Diamond” is based on “Sales Pitch,” a short story about a door-to-door salesmen and the omnipresence of advertising. In the new series, it has been refashioned into a loosely twisty story of an unhappy marriage, complete with robots. The season’s best episode, “Safe and Sound,” largely disregards the source material to explore the psyche of a teen girl thrust into a large, civilized city from her hippie, Luddite background. Black Mirror’s “what if phones but too much” has the benefit of at least being about technology we actually use.

What differentiates these attempts at televisual sci-fi short story collections? Partly, it’s the unified sensibility and roughly contiguous settings of Black Mirror. Even though Electric Dreams is based on all Dick stories, some of which share thematic obsessions with identity, reality, and humanity, the individual episodes attack those questions half-heartedly; they’re distinct enough that they rarely feel like they’re adding up to a greater whole. In one episode, humanity has evolved long past its need for a home planet, and abandoned Earth accordingly. In another, 1984-style subliminal messaging has permanently inflamed political rage, destroying a version of Chicago where everyone has to wear the same clothes. These two hours of television have a title sequence in common and little else. (In this sense, Electric Dreams is the nightmare scenario for a TV show described as “a series of ten movies”; the movies are all indistinctly related, and a bunch of them aren’t very good.) Each episode of Black Mirror may be directed by a different person, but they mostly take place in the near-present and are united by Brooker’s sensibility in a clear way, which is to say they’re bound in the same volume. The episode this season that diverted the most from this template—the black-and-white, largely silent episode “Metalhead,” is a gust of hot air, lazily floating away from the rest of the series.

The speculative fiction anthology show has a ways to go before it catches up to the potential of its literary counterparts. Of course, more labor goes into making a television show, including the split work of all of moving parts, the writers and producers and location scouts and production designers and directors and actors whose work is boiled down and condensed into the image that appears on-screen. But that doesn’t let TV off the hook for not taking full advantage of its own unique qualities, especially when it comes to a format it has done so well in the past in something like The Twilight Zone, which lowered the stakes for any given episode by fully committing to the anthology without a hint of shared universe intrigue, running half-hour episodes that consciously felt more like short stories, and literally presented its stories in black and white. The current incarnation of speculative short fiction TV would do well to consider the example of Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, a collection that reads like what a season of Black Mirror wishes it could be when it grows up.

Machado’s deliberate, often consciously elliptical prose takes full advantage of the space between words to slowy materialize a world around the reader in her own story that considers and reckons with televisual form: the collection’s best work, “Especially Heinous: 272 Views of Law & Order SVU.”

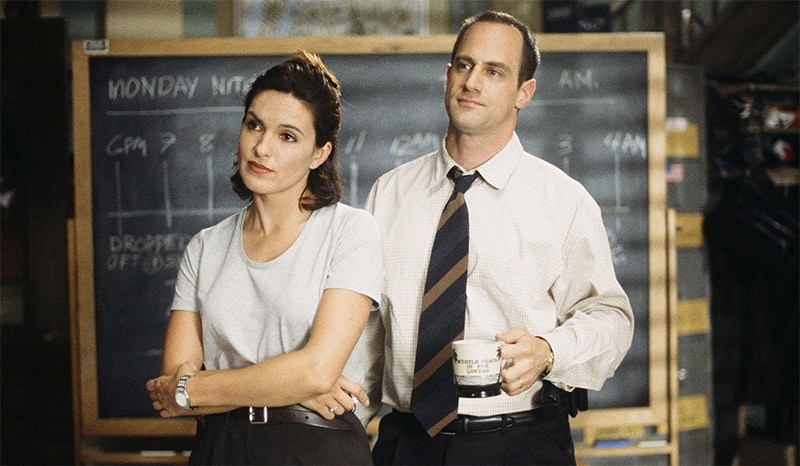

Mariska Hargitay and Christopher Meloni in Law & Order: SVU.

Mariska Hargitay and Christopher Meloni in Law & Order: SVU.

Structured as a series of episode summaries, the novella tracks the lives of SVU protagonists Elliot Stabler and Olivia Benson as they solve an endless series of sex crimes, meet their too-perfect doppelgangers, and come too close to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. There’s a relentless logic to the story; as it drops crime after crime in the laps of the heroes, it becomes increasingly obvious that Machado is interrogating the endless victims (mostly women) sacrificed on SVU’s altar, its surreal sameness and what we—and she—get out of watching the show in the first place.

The TV recap, as a format with a short half-life and rather blunt relationship to plot, is perfect for Machado’s ends in unraveling the seams that stitch together a police procedural. Her speculative fiction exists in the uneasy place where we have just enough concrete detail that avoiding visualizing the story is nearly impossible, while the images themselves still feel ephemeral. We can picture her images—girls with bells for eyes, sleek, glossy alternate versions of Mariska Hargitay and Christopher Meloni torturing the characters we know and love, the New York City streets opening up to swallow us—without the heavy-handed production design offered by Black Mirror and Electric Dreams.

As “Especially Heinous” goes on, Benson and Stabler are dogged by a loud sound that resembles a heartbeat. It is, of course, the iconic Law & Order noise, making its presence known in a world that is becoming slowly aware of its own fictionality. The boundaries between the television show and the story begin to break down, collapsing until there isn’t anything else in Machado’s New York but the words on the page and the afterimage of a now-hazy afternoon spent watching hours and hours of SVU: the uneasy feeling of not knowing what you’ve just done, while fully acknowledging the reasons you did it. It feels tragically inevitable.

This is also the exact sensation produced by successful episodes of Black Mirror and Electric Dreams, which feel like they end almost mercifully, before they can inflict an unbearable level of psychic dystopian pain. But there’s something to be said for being spare and ultimately disposable, since this is the space in which television thrives. A half-hour episode can be iconic and masterful, or it can be a slog; either way, it’s over soon enough. But these shows occupy an uneasy middle ground between light and shadow; not long enough to create the kind of full story you would expect from a film and too long to effectively allow its ideas to exist as punchy sketches that invite the viewer to think further, to draw their own conclusions. It’s a space of imagination unfairly limited. You might even call it a Twilight Zone.

Eric Thurm

Eric Thurm is a writer in Brooklyn whose work currently appears in The Guardian, The New Republic, GQ, and Esquire. He is the creator and host of the event series Drunk Education (formerly known as Drunk TED Talks).