Can Feminist Manifestoes of the Past Wake Us Up Today?

Breanne Fahs on the Lasting Lessons of Women's Anger

Breanne Fah’s remarkable collection of manifestos, Burn It Down, chronicles 250 years of feminist “rage and dreams.” It includes more than 75 vivid treatises from around the world, each a “bleeding edge of rage and defiance” where a visionary future was born. We talked, in a series of email exchanges, about these manifestos and the enduring radical promise of feminism.

*

Soraya Chemaly: Who do you think will read this book? Who do you think should read this book?

Breanne Fahs: Like all of my books, I like to think about writing and editing books that I personally want to read and that I wish existed. This is a book designed to tap into not only the cultural zeitgeist moment that we are in, particularly in terms of the painful betrayal of women happening in such a blatant way in the US, but also to recognize the transformative power of anger more broadly. So much of the academic work I read—especially outside of feminist circles—is stripped of its emotional resonance and made it to comply with “standards” that do not serve the needs of broader audiences, nor the needs of those who feel precarious or in imminent danger. In essence, this book is for those who feel enraged, fed up, overwhelmed, lonely, marginalized, betrayed, without voice, uneasy, and feral. One need not even know what a manifesto is to appreciate this particular collection. This work is about the emotional experience of transformative anger as communicated through feminist manifestoes throughout the last 150 years.

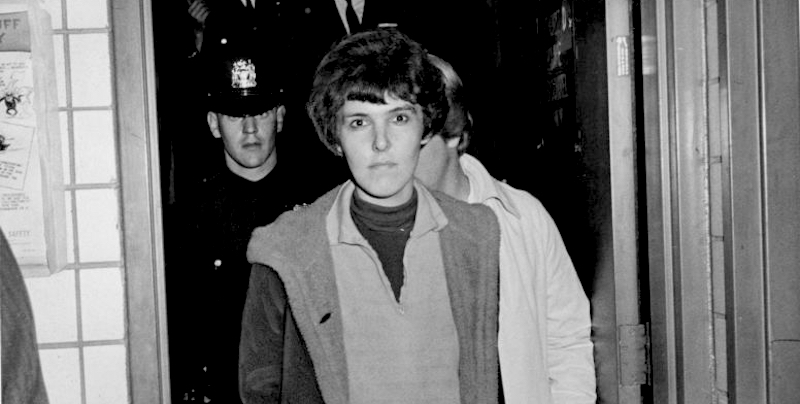

One of my favorite lines by Valerie Solanas is when she straight up says that her writing is for “whores, dykes, criminals, and homicidal maniacs.” I think there is absolutely value in making books that are for the marginalized without trying to make everyone else feel comfortable about that. I want this book to tell women that they are not alone, and more importantly, that they have never been alone in their sense of rage against patriarchy. I also think this book shows that we can feel intense solidarity with people who are raging out about issues different from our own. It is the anger itself that unites us.

And what a dream it would be, to answer your second question, if people read this book in order to better understand women’s anger, or to understand their own role in producing women’s anger. It is so difficult to talk about and within the language of anger without trying to make people feel more comfortable or at ease with it. Your work is of such immense value in how you take anger seriously without reducing its complexity.

This book is definitely also a book that does not want to put people at ease, as comfort and safety are not part of this project. (I personally think that James Baldwin was correct in describing the clinging to the value of safety as a losing proposition.) But to me, when I hear or read people telling the truth in a radical way, I feel like I can deal with reality differently and better, even if it’s painful to hear. Even as a therapist I see this. We have to know what’s real in order to really understand the depths of a problem. I believe that the more that we, as a nation, culture, and world, continue to neglect taking seriously the anger of women, the more heavy of a price we will pay for that. It may not be now or imminently in the future, but we will pay for ignoring women’s anger.

“Madness is also a great truth-teller. It shows us things that we can’t otherwise see, or that we won’t otherwise see.”

SC: What do you feel is missing in conversations about anger, women, and feminism today?

BF: It seems that there has been an unfortunate push for feminism to present itself as likable, “for everybody,” anemic, capitalistic, and smiling. This has in part happened for understandable reasons, because it’s difficult to delineate boundaries and margins with something as complex as feminism. It’s difficult and provocative to draw lines in the sand or form coalitions around specific goals. There is a role within feminism for inclusion and humor and individual transformations. But there has also been a very intense and tragic gutting of feminism’s radical history and its radical politics.

By this, I mean the goal of seeking out the root structures of patriarchy and fighting against those within broad, angry coalitions. This gutting has happened both within and outside of academia. This has resulted, among other things, in the smoothing out of feminism’s edges, the disregard for those on the margins, the flattening of the emotional range of feminism, and amnesia about the origins and roots of feminism both within this country and throughout the world. Without a return to both the anger within feminism, and the radical roots, activisms, and fury of the less “polite” feminisms, we are in trouble.

SC: I loved that you included manifestos from around the globe. As you collected these manifestos did you find central themes that united them or that were persistent and recurring? Was there an underlying ethos?

BF: I was really struck by how many of the manifestoes deeply connected to worries and concerns about economic vulnerability as connected to violence (or the potential for violence). In the same way that global warming will far more severely impact the countries around the world that are more vulnerable, women also bear a different, and often more severe, burden around the world than do men. Decisions made about reproductive rights, for example, are felt most keenly by women.

Queer and trans people bear the weight of a culture’s hatred and violence in different ways than those with more privilege. All of these manifestoes in this collection are connected by a recognition of the ways in which certain bodies and identities—especially women, people of color, poor people, and queer people—pay a heavier price than others. You can feel the anguish of that in their words. And so much of the time this anguish is forgotten, ignored, and disregarded. We as feminists sometimes forget how little most people care about the suffering of women, especially when we are looking at our own limitations.

“I love the manifestoes that are hand-written, furiously scribbled onto something, typed up with intentional typos or strange spacing, or presented with stencils of bombs on them.”

I also think there is a general ethos in this book of the value of the fight itself. I included a lot of voices in this collection who don’t have much power in their daily lives. They aren’t famous. Many are not formally educated. Some were considered criminals or “deviant” during their time. Many, in fact, endured hard deaths. Some wrote as collectives in order to obscure their individual identities. They are all, however, connected through the notion that the fight itself matters, and that angry words matter. The impulse to fight for one’s freedom and dignity is within all of us, even if more or less dormant in some of us. Maybe these manifestoes can wake us up.

For me, the collection also points to that teetering edge between sanity and madness, and it shows what happens when we are driven to the edge. I like to see these pieces as testament that madness is also a great truth-teller. It shows us things that we can’t otherwise see, or that we won’t otherwise see. Maybe in some ways this text is a call for us to stop running away from madness, and to stop diminishing its transformative power.

SC: Has the topic of anger, which seems intrinsic to manifestos, always been of interest to you? (If you’d asked me twenty years ago, I would have never imagined that I’d write a book about this.) What made you want to publish this book and now?

BF: There are many levels within which I am interested in thinking deeply about anger. I’m sure my interest in women’s anger pre-dates my interest in manifestoes and radical writings more broadly, but they do seem deeply connected to each other in my own personal and scholarly history. It’s not just that I believe in the notion of an emotional language of resistance, but I also see the ways in which patriarchy exerts itself onto women through a tight control over how they express all of their emotions, particularly discontentment, anger, and rage. In the same way that people throughout the ages have conceptualized freedom struggles, I also believe that the ability to express anger for oppressed people, both individually and collectively, is one of the only things that will lead to transformative social change.

More and more, anger seems like a supremely important and necessary subject of inquiry. The fact that this book coincides with one of the more painful recent periods of US political history will hopefully make reading angry writing more enjoyable and urgent than it might’ve been before.

I was recently in South Africa and I saw a poster there made for South African women’s day over 50 years ago. It read: “Now you have touched the women. You have struck a rock; you have dislodged a boulder; you will be crushed.“ I found that very moving and inspiring. The more I have learned about the various roles that women have played in using anger for political change, the more I recognize women’s anger as a largely under-documented entity. It is there, and has been there, but often is left out of the official historical record.

SC: I recently saw Manifesto: Art x Agency, a group exhibition examining the impact of 20th-century artist manifestos. It was a fascinating way to interpret the words, but, in fact, the words ended up seeming almost meaningless. As you worked, did you think about art or images that would be ideal pairings for these texts? As you worked, did you think about art or images that would be ideal pairings for these texts?

“When we feel more free, so much more is possible for us.”

BF: You’re absolutely correct that the history of manifestoes is largely connected to the history of art. I don’t think that’s an accident! Art is typically on the absolute cutting edge, and often is first in line to see the kinds of changes that are necessary in any particular time period. That said, I think the dominance of scholarly work on manifestoes connected to art have falsely presented manifestoes as only connected to the art world. There is a very rich history in these manifestoes that exists without visual representation. This is not to say that there aren’t a number of very interesting visuals that go with these manifestoes.

I love the manifestoes that are hand-written, furiously scribbled onto something, typed up with intentional typos or strange spacing, or presented with stencils of bombs on them. I have included some of these more visually interesting manifestoes in their original forms here. Ideally, though, I hope that these manifestoes inspire readers to think about art, imagery, and the whole language of resistance that is possible through the the act of creation.

SC: Do you have a favorite piece or a particular expression or sentiment from the book?

BF: I spent about ten years working on the biography of Valerie Solanas, in large part because I find her endlessly fascinating and provocative. She is such a difficult character, and such an important one to the history of feminism. One could also argue that she is crucial to the history of women’s anger. I absolutely adore the SCUM Manifesto for its provocations, unresolved complexities, laugh-out-loud humor, truth-tellings, freshness, fury, and unsettling imaginations about the world. But I also love the way that she imagines a world where women are free to prioritize friendship, art, brashness, and laughter on their own terms. This manifesto gets to the bottom of what this collection is trying to show: when we feel more free, so much more is possible for us.

Breanne Fahs is Professor of Women and Gender Studies at Arizona State University. She is the author of Performing Sex, Valerie Solanas, Out for Blood, and Firebrand Feminism, and co-editor of The Moral Panics of Sexuality and Transforming Contagion. She is the Founder and Director of the Feminist Research on Gender and Sexuality Group at Arizona State University, and also works as a Clinical Psychologist.

__________________________________

Burn It Down!: Feminist Manifestos for the Revolution is available via Verso Books.

Soraya Chemaly

Soraya Chemaly is an award-winning writer and media critic whose work focuses on inclusivity, free speech, sexualized violence, and technology. She is also co-founder and director of the Women’s Media Center Speech Project, Her recent book, Rage Becomes Her: Women and Anger, was named a best book of 2018 by Fast Company, Psychology Today, Book Riot, Autostraddle, and the Washington Post.