My dog has a carbon footprint. She loves food for one thing, especially meat, and sometimes I keep the heat turned up a few degrees for her when I leave the house. In a strictly economic sense, her productivity (the ratio between output and input volume) is zero. She has no measureable output—she doesn’t work, which is ironic because she’s classified as a “working dog,” bred to herd cattle. She is not a service animal, insofar as she doesn’t wear a vest and no one has ever filed any paperwork, but she does have a job, and that job is complex and important, and therefore worthy of consideration.

Dogs, as Sigrid Nunez examines in her National Book Award winning novel, fall somewhere between idyllic (as Kundera describes their relationship to humans) and celestial-furry-guardian-spirits (as Nunez’s narrator muses). The Friend is, on its face, about Apollo, a dog left behind when his master commits suicide. But it’s also a meditation on writing and writers. As I read it, I couldn’t help but wonder: Is there some indelible link between dogs and writing? The sheer number of dogs in literature should tell us something not about dogs but about humans.

Dogs cannot be characterized by dialogue or thoughts (anthropomorphized interiority, maybe), so why is literature so obsessed with them? Dogs change humans. Dogs reveal human wants and vulnerability. Dogs, ultimately, make humans more human.

So, if my dog’s primary job is to make me more human, then she is productive, very productive, even measurably productive in an economic sense. Perhaps Richard Thaler could spare a grad student or two for further study?

Making humans more human is a lot like purchasing carbon-offsets. After all, no environmentalist would ever say people ought to get rid of family dogs. Oh wait, no! Gregory Okin wrote a paper on it, wherein he concluded: “meat eaten by pets is responsible for the release of about 64 million tons of CO2 per year,” which is a lot. Okin has a point, but that doesn’t mean I want to have a beer with the guy. I’m definitely not hiring him to dog-sit.

Environmental impact aside, dogs cost money and require significant time, which includes rather unpleasant tasks such as picking up poop and vacuuming dog hair. And, as the adage goes: time is money. Unless you’re a dog.

*

My dog’s relationship to time is binary: time with her humans (me, my husband, and baby) and time without us. Because time is binary—this or that—its value is also binary.

Time is the thing we all have but don’t understand how to value. American culture, in all its complexity, is still hung up on the Protestant work ethic and the Invisible Hand. Hegel would be disappointed in us—here, the sweep of history has caught a snag. The way we value time has not evolved. Devolved, more likely.

A friend once told me that she didn’t believe in the idea of being too busy. “No one is too busy for anything,” she said, “People just prioritize certain things over other things.”

She’s right, of course. People say they are too busy as a shorthand. Being too busy circumvents the hierarchical thinking that prioritization demands. No one says that work is more important than love, or that sex is more important than a friend, or that social media is more important than staring into a child’s eyes. We just say: we’re too busy. It’s an easier thing to say.

If my dog’s primary job is to make me more human, then she is productive, very productive, even measurably productive in an economic sense.

But refusal to acknowledge the hierarchy of choice is not our gravest problem. We are incapable of assigning value to time. More specifically, we constantly assign value but rely far too heavily on productivity (in the aforementioned economic sense) and material success. In other words, people who make a lot of money tend to think their time is more valuable than people who do not.

Steve Jobs famously parked in a handicap parking spot near his building’s entrance. Walking through the parking lot takes time! Meanwhile, a writer struggled to defend her “writing time” against all odds. Announcing to your spouse that you plan to spend all day every day working on a novel that may or may not sell in two to five years is a difficult conversation. On the other hand, telling your spouse that you’ll be at the office until 2am because your company is changing the world, so you’re sorry but you won’t be home to feed the baby and change the diapers and give him a bath and read him a book, isn’t a difficult conversation. It arrives in the form of a text: Stuck at work.

The thinking that underlies these dynamics is not magical. It’s economic. Value, in economic terms, is defined by scarcity, and people who work a lot believe their time is very, very scarce. People who are paid a lot believe their time is even more scarce because no one else could possibly do what they do (changing the world is hard!). By this measure, Steve Jobs should have parked in that handicap spot. People need better cameras on their phones, damn it!

Steve Jobs apparently banned dogs from Apple’s campus when he returned to the helm in 1997. He clearly missed the memo. Those dogs made their humans more human, Steve! At the very least, they deserved severance packages.

The value of time is by no means a simple analysis and many socio-economic issues are at play (too weighty to dive into in an essay that is mostly about my dog). But for the average American who repeats “I’m too busy” like a personal mantra, time is not necessarily scarce. As my evolved friend pointed out, it’s a matter of prioritization. Our value judgements are askew.

Ask the dog. She makes a single value-judgement: time spent with the people she loves is worth the most. This is a profound lesson in humanity. She deserves a bonus!

*

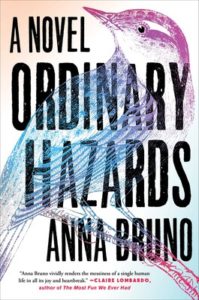

There is something else: dogs spend most of their time at home. Home is the place they love—the place they protect. The mailman is the enemy! In Ordinary Hazards, Emma observes: “A dog’s nose is a steadfast compass, always pointed towards home.” Dogs understand that long walks are fun but the real prize is coming home again.

In the end, dogs have one last job: they remind us of our mortality. My dog is eight, going on nine, and often I am struck by the notion that she will surely not live past fifteen. Fifteen would be a gift. This feeling has led me to rub her belly and kiss her forehead on numerous occasions. On the other hand, I don’t stroke my husband’s arm at the thought of potentially having, say, forty more years with him. Of course, I should. But then he’d be like, “What are you doing to my arm?”

A dog may not be aware, exactly, of her own longevity, though she surely feels her age. Time is binary but it is not infinite. And any human who has ever lost a dog knows all too well that time doesn’t slow, but for a lazy afternoon or a long walk in the park.

__________________________________

Ordinary Hazards by Anna Bruno is available now from Atria Books.

Anna Bruno

Anna Bruno is the author of Fine Young People (Algonquin, 2025) and Ordinary Hazards (Atria, 2020). She teaches at the University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business and the Iowa Summer Writing Festival. Previously, Anna managed public relations and marketing for technology and financial services companies in Silicon Valley. She holds an MFA in fiction from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, an MBA from Cornell University, and a BA from Stanford University. She lives in Iowa City with her husband, two sons, and blue heeler.