Can a Little Bit of Data Make Parenting Easier?

Emily Oster Talks to Pamela Druckerman About Her "Parenting Book for Economists"

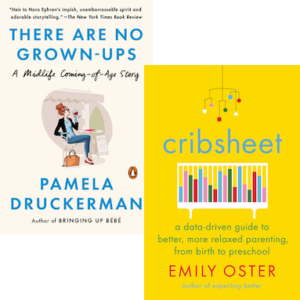

Pamela Druckerman, author of There Are No Grown-ups: A Midlife Coming-of-Age Story and Emily Oster, author of Cribsheet: A Data-Driven Guide to Better, More Relaxed Parenting, from Birth to Preschool, discuss parenting, data, and writing about children.

*

Pamela Druckerman: I’ve thought of many ways to begin this conversation. Some of my openers were just bad jokes: “What’s with you and data?” “Why did you decide to write a parenting book for economists?” I think I’ll just begin sincerely: Cribsheet is clearly written and packed with the kind of data that’s gold to new parents. Not all academics manage to write well for a general audience. Are your academic articles this easy to read, too? Or are you really a writer trapped in the body of an economist?

Emily Oster: It’s interesting, I think when I look at my academic work my writing is increasingly influenced by having spent this time writing books. So, I think it is probably easy to read, but not always “academic” enough. My husband read one of my recent papers at some point and asked me, “Why do you spend so much time explaining what you are going to do?” This was a fair point. Writing for academics most people tend to assume everyone knows the background and has a common language. Not so with writing for non-specialists. I tend to be more pedantic than most, which I think bothers some people but also makes my papers easy to assign in, say, undergraduate classes. I do think I’ve always found the writing part of academic papers to be the easier part (relative to, say, the mathematical proofs) so maybe it was always destined to be. My mother did bring by some stories I wrote as a kid the other day and I thought they were not too bad. No data, though. I’m curious—for you—you write both short-form pieces and books. Do you find the process very different? Or do you think of the books as just an extended form of an essay?

PD: An anthropologist I know says that the big problem with academic writing is: Not enough suspense. Imagine if Pride and Prejudice started with an abstract that said, “After a series of conflicts and misunderstandings, Darcy proposes to Elizabeth and she accepts.” I find all writing hard—from 800-word columns to 60,000-word books. If I’ve been doing lots of columns they start to get easier; it’s as if I’ve created enough momentum to power through my doubts. But I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to sit down and write, angst-free, like it’s an ordinary job. Since you brought up your childhood… yours wasn’t exactly ordinary. Your parents put a tape recorder in your crib and recorded your conversations with yourself. And these were widely studied by linguists. What kinds of things did you say?

“I usually arrived at solutions to parenting problems only once my own kids had aged out of that particular problem.”

EO: Yes, my parents did this. It’s the ultimate in navel-gazing. Mostly I talk about what happened in my day and what is happening tomorrow or in the future. “Tomorrow we go to Child World, and get diapers for Steve [my brother], and MAYBE mom will get me a toy.” And so on. I think for the linguists the structure is more interesting than the content. It’s funny, though, I recognize this need to plan in advance and talk to myself about it in me as an adult. I definitely still do this. Sometimes I’ll be walking around basically talking to myself about what is going to happen in my next meeting or something; Jesse will catch me and be like “Are you on the phone?” Um… no. Maybe everyone does this?

PD: I do talk to myself when I’m alone, but it’s usually about past events and conversations; all the clever things I should have said, but didn’t. The French call this “the wisdom of the staircase.” Your technique sounds far more productive. Speaking of productivity: let’s talk more about work. We both came to writing about parenting from other fields. I just heard an interview with the music producer Rick Rubin, who said it’s great when a producer who isn’t that familiar with, say, dance music, suddenly produces a dance-music album. The album is more inventive. It has fresh ideas.

I think the genre of parenting books called out for this kind of reinvention, and it’s now being pulled in lots of new directions. Cribsheet is a case in point. You don’t cherry pick one study about sleep, to bolster a pre-existing parenting philosophy. You look at many studies, and even studies of studies! I love studies of studies.

EO: Studies of studies! “Meta-analyses.” I often describe my books to people as a cross between a memoir and a meta-analysis. There is a fine line in both directions on this book because I do not want to either say, “Here’s what I did, I’m an expert, trust me,” nor do I want to go through all 700 studies of breastfeeding and lower respiratory infections and discuss their pros and cons.

A lot of the writing work of the book is figuring out which studies or studies-of-studies I want to highlight and how to explain why I picked those. I do also think there is an important point here about not bolstering any particular philosophy. I think there are a lot of great “how-to” parenting books. If you want to sleep train, there are books about literally what to do in order to achieve that. Or baby-led weaning (no baby food); plenty of books which will tell you how to give them baby carrots. Cribsheet is more like how to decide which of these other books you should buy. I don’t exactly tell people how to sleep train (although I do specifically say what we did), but hopefully I will help them decide if it is for them or not. There are a lot of other economists now who have told me they want to write books about parenting or kids. It can be a new genre.

PD: Ha! I often describe my books as a guide for the perplexed, by the perplexed. Which makes it feel odd when parents occasionally approach me to ask for advice. How do you cope with that role? I stand behind all my research and reporting, but I don’t want to be on the mountain, issuing edicts. Though I think my edicts would mostly be about cheese.

EO: I struggle with this so much, especially because I am a naturally bossy person who always wants to tell people what to do even if I do not have the research or data to back it up. One of the good things, I think, about this book is it forced me to constantly confront that, actually, there are many good choices. I’m now going around telling people that they should make the choices that works for them, so I’m trying to contain the bossiness that I bring to my personal interactions. I find that I’ve just altered what I’m telling people to do. Lately, I’ve been telling people they have to get an Instant Pot.

PD: I’m so glad you brought up the Instant Pot. I thought it would change my life. But it turns out that you still have to buy things, chop them up and put them inside the pot. That’s two more steps than ordering take-out. Wait, was that a product placement?

EO: I don’t think it can be a product placement if it comes in a generic. I bought the Instant Pot at the same time my husband bought this Sous-Vide machine. Our kids made fun of me for talking about the Instant Pot all the time but I will say that he has used his machine once and I use mine most days. It is harder to do than take-out, but a lot easier than stove cooking.

PD: That pause was me Googling “sous-vide.” I also wanted to ask you about being a parenting writer while raising small children. There seem to be several paradoxes at work. The first is that researching and writing takes a lot of time, which is time one can’t spend with one’s actual kids.The other may just be a personal paradox: I usually arrived at solutions to parenting problems only once my own kids had aged out of that particular problem. For example, I never got to use the “French” method of teaching babies to sleep through the night, because my kids were older by the time I figured out what the “French” method was. This definitely doesn’t apply to you, but it’s also worth pointing out that some of the best-known parenting theorists were famously terrible parents. Rousseau I think didn’t even acknowledge paternity of his kids.

“There are some sacrifices in parenting.”

EO: I think there is a reason this book was written after my second kid has just about aged out of it. With the first one I felt like I was totally out of control much of the time, especially in the beginning. There were so many decisions I hadn’t thought about, there wasn’t time to give them the kind of data-decision treatment I like. When I had the second, I had more of a chance to ask, okay, how do we want to make these choices since I had a (slightly) better idea of what they are. But there were definitely things I didn’t think about and then had to deal with and now think I would have done differently. Finn had jaundice as a baby and in retrospect if I had been better prepared I would have tried to treat him at home, not go to the hospital since it was a super mild case. But since Penelope didn’t have this, I wasn’t prepared. And when you have a four-day-old baby you’re not super-equipped for research.

There was at least one thing where the book changed my parenting, which was discipline. I hadn’t thought to include this and then my editor (also yours!) the incomparable Ginny Smith, told me to look into it and it turned out there was actually a lot of empirical support for a particular approach. Ginny was happy since she had already been using that one. But we definitely adopted it in my house. Usually my books are kind of backward-looking though. You do wonder if people practice what they preach. Like, was Dr. Spock a good dad?

PD: How did you feel about writing about your children? I tried not to include details about mine that might feel too intimate or embarrassing later. Though so far they’ve expressed no interest in reading the book.

EO: I had my daughter read some of the parts of the book about her, although she lost interest. I tried, like you, to leave out any embarrassing stuff. The baby stuff is easier since it’s more removed. I didn’t put in details about potty training. I’m surprised your kids haven’t read yours! It’s so fun.

PD: Thanks. One of the arguments I make in Bringing Up Bébé is that many of the parenting habits that the French practice en masse—like encouraging kids to taste a food many times, even if they think they don’t like it—are validated by scientific studies. I was gratified to see that some of these techniques are also endorsed by your book. Whew!

EO: Yes! There are some good tips in there about how to get your kids to eat, based in part on studies where researcher video tape people eating with their kids. They find kids do better if you say things like, “Try that, you might like it.” Instead of “if you don’t eat that, no dessert/iPad time/etc.” This is one of these things I find hard in practice. Last night we had this very delicious vegetable pie thing, and my four-year-old just emptied out the veggies and ate the crust. It felt so wasteful. You want to be like “WHAT IS THE MATTER WITH YOU THESE VEGETABLES ARE DELICIOUS.” In the end, I ate his veggies and gave him my crust. It was too bad as I also like pie crust. There are some sacrifices in parenting.

“A lot of the focus, especially in Cribsheet, is on taking a step back, structuring the decision, thinking about your preferences in a somewhat dispassionate way and then choosing based on costs and benefits.”

PD: Speaking of parents, if Wikipedia is to believed, yours are both economists. And then you became an economist yourself… and married one! And then you wrote parenting books. Explain!

EO: I think there is always a “just so” nature of one’s origin story, but I do think all this economics-in-the-home influences my books to some extent. A lot of the focus, especially in Cribsheet, is on taking a step back, structuring the decision, thinking about your preferences in a somewhat dispassionate way and then choosing based on costs and benefits. That is a very “economics” way to make decisions, maybe somewhat different from something like, “do what feels right.” When I was a kid, I got the sense my parents made at least some of their decisions like this. And definitely having a partner with the same kind of training is useful, since we usually approach things the same way. He is actually much more logical about family decisions than I am.

But it is for sure a bit odd to have all these economists around. My brothers are not economists, but one of them is married to someone who also works in the economics space. And my mom is always trying to teach the grandkids about supply and demand. With my ten-year-old nephew she has even pulled out some textbooks to try to work through. I fear for the next generation.

PD: And yet despite all the data, in your life and your book, I liked the part of Cribsheet where you said you chose your children’s nanny based not on data, but on intuition. (I’m guessing you also called some references!) It seems like an acknowledgment that data can guide some decisions, and maybe push us in the right direction, but we are also shaped by feelings and less analytical impulses. And, of course, we’re shaped by culture. Might the impulse to parent based on scholarly findings be an especially American one—along with the idea that we can constantly improve ourselves? The arc of parenting is moving toward… better parenting?

EO: I think this last is more for you! Certainly I do think Americans (at least some of us) are into “optimization” and “evidence-based parenting.” At least I hope people are, since that’s my audience. I have the casual impression Europe is a bit different, but I think one always has to be careful about relying on anecdote. What do you think? Are the French into evidence-based parenting?

PD: A Parisian friend of mine thought it was fascinating and strange that some American parents hold their kids back in school, because stats allegedly show that older kids have an advantage over younger ones. Parenting hasn’t quite risen to the level of a competitive sport here! And newspapers don’t usually run features on how to improve your children, or your life. That said, there are French parenting books, and some of these contain research. I suppose the main difference is that parents here don’t feel that they have to decide everything practically from scratch, and make endless choices about the best way to raise kids. As you point out—it’s implicit in your subtitle—this decision-making process injects a lot of anxiety into the process.

The French take for granted, at least more than we do, that lots of techniques and approaches have been sorted out. They don’t have to choose. There’s an evolving cultural consensus. And as I mentioned, the methods they’ve adopted out of pragmatism and habit are quite often the things that the research points to anyway. This doesn’t take all the anxiety out of parenting, but it does calm things down.

EO: Yes, I do think that the number of choices is a lot of what overwhelms people. I talk in the book about some very early experience where my mom told me not to put mittens on my kid because she wouldn’t learn to use her hands, but the doctor told me that she would scratch herself. I did some research on this—I’m not kidding—which of course yielded nothing. But I obviously felt at the time that this was an important choice I had to make correctly. I think I would have been much better off if culture just informed me that either you use mittens, or not. I mean, granted I am a more hyper-neurotic person than most but I think I am not completely alone!

PD: You’ve heard that ancient blessing, “May your children grow up to be economists,” right? Or maybe it was not economists. I always forget. Seriously, it’s been a pleasure exchanging both parenting and literary thoughts with you. I’ve spent a lot of time recently thinking about what makes someone a grown-up, and I’m pretty sure you are one. Though I’m guessing that, even when you were in the crib, you already had plenty of wisdom. Here’s to parents—and writers—everywhere, just trying to do a good job with their kids. Because one day soon, they’ll be writing books about us.

EO: I agree; this has been a pleasure. I am not sure I’m a grown-up, but I’ll take the vote of confidence.

![]()

Emily Oster is a professor of economics at Brown University and the author of Expecting Better (now out in paperback) and Cribsheet out now. She was a speaker at the 2007 TED conference and her work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and Esquire. Oster is married to economist Jesse Shapiro and is also the daughter of two economists. She has two children.

Pamela Druckerman is the author of four books including the international bestseller Bringing Up Bébé, which has been translated into twenty-eight languages, and There Are No Grown Ups (out in paperback April 30). She’s also a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times.