“Camp is a Sensibility.” On Susan Sontag, Extravagance, and Sexuality

Amelia Abraham Considers a Queer Icon

I have a memory. I think I was about 13 years old—probably wearing dungarees, or at least, that’s how I like to imagine my proto-lesbian self. I was kneeling in my parents’ living room and slotting a VHS into the recorder. The film was called The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, a nineties cult classic about two drag queens and a Transgender woman who go on a road trip across the Australian outback. It was the first time I had watched the film and I remember the opening scene distinctly: a drag queen in a big blonde wig pads onto the stage in a dingy club and starts doing a number, a lip sync to a dramatic seventies ballad. “What the hell is this?” I thought—I had never seen drag before, but I was instantly hooked. The film’s strapline, which was printed across the VHS box, seemed appropriate: “Drag is the drug,” it read.

Looking back now, there’s one moment that really stands out in my mind from Priscilla, and that’s when Guy Pearce’s character, Felicia, sits atop the giant silver stiletto that’s fixed to the roof of the tour bus the queens are traveling in, and performs a stellar lip sync to a song from the opera Madame Butterfly. First, we’re given a close-up of the beauty look—high, arched eyebrows painted rudely onto Pearce’s face—before the camera slowly pans outward to the reveal: the outfit, a glistening silver-sequined catsuit, then that ridiculous giant shoe, then the vast expanse of the Australian desert. The final touch, although I wouldn’t quite clock it until I rewatched the film years later, is the graffiti that was sprayed onto the side of the bus in a previous scene: “AIDS fuckers go home.” Horribly homophobic, yes, but Pearce’s performance steals the shot, as if to say: “Whatever insult you throw at me, I’ll always be fabulous.”

I didn’t know it yet, but watching this film was a pivotal moment in a long-standing love affair for me. A love affair with all things camp.

I’ve been consuming camp for as long as I can remember, before I learned that there was a word for it. Bands I loved, like the Spice Girls and Steps, were camp; so were the aunts in Sabrina the Teenage Witch, and my favorite childhood film, Hocus Pocus—mostly because it had Bette Midler in it, and anything Bette Midler does is camp. The first cassette single I bought was Cher’s Believe (guilty), which was iconically camp— whether or not it flew under my seven-year-old radar. I loved to watch the high-drama performances on the Eurovision Song Contest, too. And remember that Simpsons episode “Homer’s Phobia,” where the godfather of camp and trash, the filmmaker John Waters, plays Marge’s new gay best friend, the owner of a kitsch bric-a-brac store? Definitely my favorite Simpsons episode, and one of my earliest memories of camp.

A lot of us have camp tastes when we’re children—some of us grow out of them, others grow up to be homosexual. It turned out that I am in the latter group, which meant that, at 19, now more familiar with the word “camp” and newly familiar with my own queerness, I wanted to know more about it. I understood that “camp” was often used as a way to describe someone or something effeminate, usually gay men. It was also a term used to describe a lot of the kind of films, TV shows, and pop music I liked. But what made them camp exactly, I wasn’t sure. In all honesty, I was a little confused by the word. Was it a way of being? Or a way of seeing things? In fact, until I found the writer Susan Sontag’s famous 1964 essay, “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” I don’t think I could have put it into words.

I didn’t know it yet, but watching this film was a pivotal moment in a long-standing love affair for me. A love affair with all things camp.

Sontag’s essay explains that camp is a sensibility, a “mode of aestheticism,” “a private code,” “a badge of identity, even.” The hallmark of camp, she says, is the spirit of extravagance. It can be broad (as disparate as Bette Midler and John Waters are, their camp qualities unite them), but certainly not everything can be camp; in fact, it’s really quite particular. “Indeed the essence of camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,” Sontag writes, adding that “camp sees everything in quotation marks.” It is something that ties together theatricality, irony, and, sometimes, a certain self-awareness. While the aforementioned director John Waters’s films know themselves to be camp (think a drag queen playing the matriarch of a suburban family), some 1930s musicals, for instance, are camp without meaning to be. Sontag divides it up into two neat categories for us: there is an accidental kind of camp, or “naive camp,” she says, and a more “deliberate camp,” that is aware of itself.

As for the link between camp and homosexuality, “it has to be explained,” muses Sontag (actually, she was going to call the essay “Notes on Homosexuality,” but later changed her mind). The dandy writer Oscar Wilde was an early forerunner of camp, she notes—hence why “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” is dedicated to him—but of course there are many more examples. “While it’s not true that camp taste is homosexual taste,” writes Sontag, “there is no doubt a particular affinity and overlap.”

Reading Sontag’s essay as a 19-year-old, and one who was grappling with my sexuality, something seemed to slip into place. “Notes on ‘Camp’” not only helped me to grasp the meaning of camp or to explain a lot of my weird cultural tastes, but it gave me something extra. Just months after confronting all of the difficult feelings that came with sleeping with a girl for the first time, in camp, I felt like I had inherited a special gift, a secret language, a very particular kind of humor. Camp felt like a weapon to use against the world when I might find myself up against homophobia—a source of joy in difficult times. But on top of that, I had gained something else. In Sontag, I had found a new queer hero.

*

After I first read “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” I went in search of Sontag’s other books, and found that, similarly, they made other intangible ideas feel tangible. They took on nebulous topics I had spent a lot of time thinking about but had struggled to theorize. Against Interpretation, which contains “Notes on ‘Camp’” and which was published in 1966, questions the ways that we are taught to respond to works of art, through thinking and feeling. On Photography (1977) looks at the complex relationship between photography and voyeurism, and Illness as Metaphor (1978) asks how and why we imbue certain illnesses with meaning. As I consumed her always considered, always eloquent writing, I noticed that Sontag seemed to give equal gravitas to what we might consider “high culture” and “low culture,” always keen to analyze the things that the rest of us think of as ordinary. This seemed to me like a good way of looking at the world. As her son, David, famously said of her: “My mother was someone who was interested in everything.”

But it wasn’t just through her writing that I got to know Sontag; it was through photographs, too. Of which there are many that stand out to me. One is the shot of her taken in New York City by Jill Krementz, in 1974, in which she is smoking a long, thin cigarette nonchalantly, and staring directly into the camera, holding our glare. Another is the beautiful and very well-known 1975 Peter Hujar portrait of a youthful-looking Sontag lying on the bed in a ribbed sweater, gazing upward absentmindedly. And then, of course, there are the images of her taken later in life, with her (practically trademarked) thick gray streak of hair jumping out of the frame, many of which were captured by her long-term lover, the renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz. To this day, the only thing that makes me feel OK about my own rapidly graying hair.

Sontag had a string of relationships with both men and women, but her relationship with Leibovitz was arguably her most significant. They met in 1989, when Leibovitz was taking Sontag’s headshot for the book AIDS and Its Metaphors, a follow-up to Illness as Metaphor, that examined the cultural connotations of the HIV virus, which was ravaging the New York City in which Sontag lived at the time. According to Benjamin Moser’s biography, Sontag, Sontag and Leibovitz instantly started a relationship, but when Sontag’s assistant asked her about it, she initially denied it, and bristled at the use of the term “lesbian,” saying that she didn’t like labels, particularly that one. From talking to countless people who knew the couple, Moser describes how Sontag was cruel to Leibovitz, mocking, patronizing, sometimes tormenting her.

Their relationship was the longest of Sontag’s life, lasting fifteen years, but both women were famously private about it, at least until after Sontag’s death in 2004. Controversially, in the autobiographical book A Photographer’s Life 1990–2005, Leibovitz published photographs of Sontag naked, as well as images of a vulnerable, brittle Sontag in her hospital bed, not long before cancer (leukemia) took her life in 2004. That Sontag never came out publicly is something that she has been criticized for. But as the incredible New York writer, and Sontag’s friend, Fran Lebowitz says in the documentary Regarding Susan Sontag, “This is an unfair thing to say about anyone, but to me it’s an age thing—for someone my age it is a private thing . . . for someone my age it has to be a secret thing.” The gay American poet and cultural critic Wayne Koestenbaum, who is also in the documentary, takes another approach: “Does the author of ‘Notes on “Camp” ’ have to come out?” he asks.

From Sontag’s writing, it’s clear that she struggled with her own sexuality, but that this struggle drove her passion, her work: “My desire to write is connected to my homosexuality,” she wrote. “I need the identity as a weapon to match the weapon that society has against me. I am just becoming aware of how guilty I feel being queer.” These words have made me question why I have forged a career writing mostly about my own sexual identity as well as LGBTQ+ issues, whether it’s a kind of self-defense mechanism, or a way of owning my own narrative.

Choosing to only write about her sexuality privately suggests that Sontag was perhaps ashamed of this part of herself. Or perhaps she simply felt that her sexuality was no one else’s business. Or perhaps it was more complicated than that; Susan had a son, she was a very public figure, and she was often condescendingly labeled a “woman writer”—she may have felt compromised, or like she was up against enough already. Plus, to put things into perspective, she met Leibovitz at the height of the AIDS epidemic (highly stigmatized and described by some as the “gay disease”), homosexuality itself was still illegal in parts of America until as late as 2003, and Sontag was living in a time when there were very few gay or bisexual women in the public eye. Many people did know about her love life, of course, but for her to discuss it more openly may have impacted her career, her family, her personal relationships.

In many ways, Sontag was a victim of the time in which she lived, a time when same-sex love affairs were often shrouded in secrecy, when a lot of people lived “in the closet.” That David Rieff, Benjamin Moser, and Annie Leibovitz have exposed so much of Sontag’s intimate life since her death brings up ethical questions about a person’s right to privacy when they are no longer with us. But it has also given more of her queer history to the world, and in doing so has allowed people like me to discover her as a (complicated) role model, to think of her in the canon of great LGBTQ+ thinkers along with the likes of James Baldwin and Gertrude Stein. Sontag’s diaries remain a rare and honest testament to what it means to be a young woman falling in love with another woman for the very first time.

__________________________________

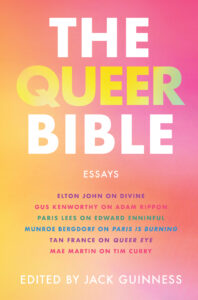

Adapted from The Queer Bible: Essays edited by Jack Guinness. Copyright 2021 © Amelia Abraham. To be published on June 15, 2021, by Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Adapted by permission.

Amelia Abraham

Amelia Abraham is a London-based journalist and author. She has worked as an editor at both VICE and Dazed, and writes for The Guardian, Vogue, and other titles. Her first book, Queer Intentions: A (Personal) Journey Through LGBTQ+ Culture, was published by Picador in 2019. A first-person exploration of the mainstreaming of queer culture, Amelia goes to Britain’s first same-sex wedding, travels to RuPaul’s DragCon in LA, parties at Pride parades across Europe, and investigates the violence experienced by Trans people in New York City. Munroe Bergdorf described it as “an intersectional and insightful journey through the nuances of the queer experience.” Amelia’s second book, We Can Do Better Than This, is an edited anthology, asking queer pop stars, performers, academics, and activists the question: “If you could change something to make life better for LGBTQ+ people, what would it be?” The result is a definitive and global guide to queer activism. Outside of writing and editing, Amelia curates and speaks at events usually revolving around LGBTQ+ rights or queer culture. In 2018, she gave a TEDx Talk called “Why Feminists Should Support Transgender Rights.” She wants to write the greatest lesbian rom-com of all time, but hasn’t got round to it yet.