Camonghne Felix on Humiliation, Trauma and Finding Comfort in Computers

"All day, I would think about that empty computer screen and what lay behind it for me."

The exact first time I touched a computer I can’t recall, but in the heavy-wooded armoire of my mind I can find stacks of them, every single one built by my mother, nearly from scratch—constructing motherboards memory by memory, that lockbox of formulaic intent humming with the blood of her calculated intellect.

When we were small, I watched her build them all the time, with either one of my sisters strapped to her chest, her arms bent in a bowl so as not to disturb them as she screws a power connector into its corresponding socket, Bunny Wailer wailing in the background. She caresses the enamel of the shell once built and functional, praying over it, honoring its capabilities. Only after that ritual would she install the games I wanted to play—Math Blaster!, You Can Be a Woman Engineer—collapsing the spine of the desk chair so that my eyes would rest level with the great pixelated sky of the monitor.

I was supposed to have a four-hour-a-day limit on the computer for intellectual posterity but sometimes, while my mother slept, I would creep down the short hallways from her bedroom back into mine, where the big fantastical box of formulas would await me, teasing me with the confidence of the millennium, urging me toward Egypt where my friend Carmen Sandiego would leave clues for me, her red wings whipping in the pixeled sand.

All day, I would think about that empty computer screen and what lay behind it for me, intentionally misbehaving until someone would send me back to my room as punishment, where I could sit delighted, fixated, tantalized as the night fell down around me, the eclipsing light falling across my cheeks like an even snow.

Little by little, I begin to think in the computer’s language, its pointer shaping the contours of my dreams. I was dreaming in programs and codes and colors and compounds, dreaming in trapped doors that open with modular keys, dreaming in the voices of my virtual guides, dreaming from behind the wheel of a car powered by good grammar, Mavis Beacon’s wily tone lulling me to sleep, singing to me: “Good job. Are you ready for the next lesson?”

Those were the days when I loved math. I swear I did.

I smelled the scent of that familiar, musky vigor, and I left my body.

When I was very young, like ten or eleven, having already lost the silent right to my girlhood, I discovered the body to be a sexual body with portals and buttons that open to the heavy hand of heat. And I also discovered porn. It was when I discovered porn, slowly and precisely uncovering each corner of the cloaked web, that I discovered kink, and as I discovered kink, I discovered one immutable fact of human nature: there is something in all of us that craves the shadow side of abject humiliation.

It was second grade when I realized I was different, and it would be a tragedy.

When I was distracted, I would float high above the room, noticing everything, the way the clock ticked, how the dust on the board settled, the way the corners of the carpet frayed, how the room itself smelled, the wind from the outside wafting the spring in.

I thought to myself that the room smelled like sex. And I didn’t realize what I was thinking until I’d said it out loud. My twenty-something-year-old teacher, mortified, just stares at me for a moment, because wtf. Because how horrid to hear an eight-year-old say something so ominous, so unusual. When I said it, the room gasped, children’s voices aflurry, and suddenly I was back down on that alphabet rug, no longer floating, red with the humiliation of what I had said out loud.

But I knew what I knew. Like a locket, that smell was its own memory. I smelled the scent of that familiar, musky vigor, and I left my body. That was the truth. In a few moments, I’m whisked out of the classroom and into the front office, where I sit in the big leather chair next to the check-in desk as I would if I were my own parent. I can’t recall what happened next.

“It’s such a fuckin’ old pain that, you know, there’s nothing poetic about it,” Fiona sings, and shit if that’s not true.

__________________________________

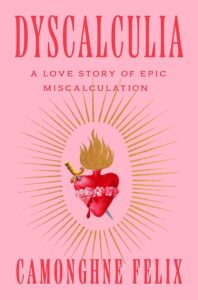

Excerpted from Dyscalculia by Camonghne Felix. Copyright © 2023. Used by permission of One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Camonghne Felix

Camonghne Felix, poet and essayist, is the author of Build Yourself a Boat, which was longlisted for the National Book Award in Poetry, shortlisted for the PEN/Open Book Award, and shortlisted for the Lambda Literary Awards. Her poetry has appeared in or is forthcoming from Academy of American Poets, Freeman’s, Harvard Review, Lit Hub, The New Yorker, PEN America, Poetry Magazine, and elsewhere. Her essays have been featured in Vanity Fair, New York, Teen Vogue, and other places. She is a contributing writer at The Cut.