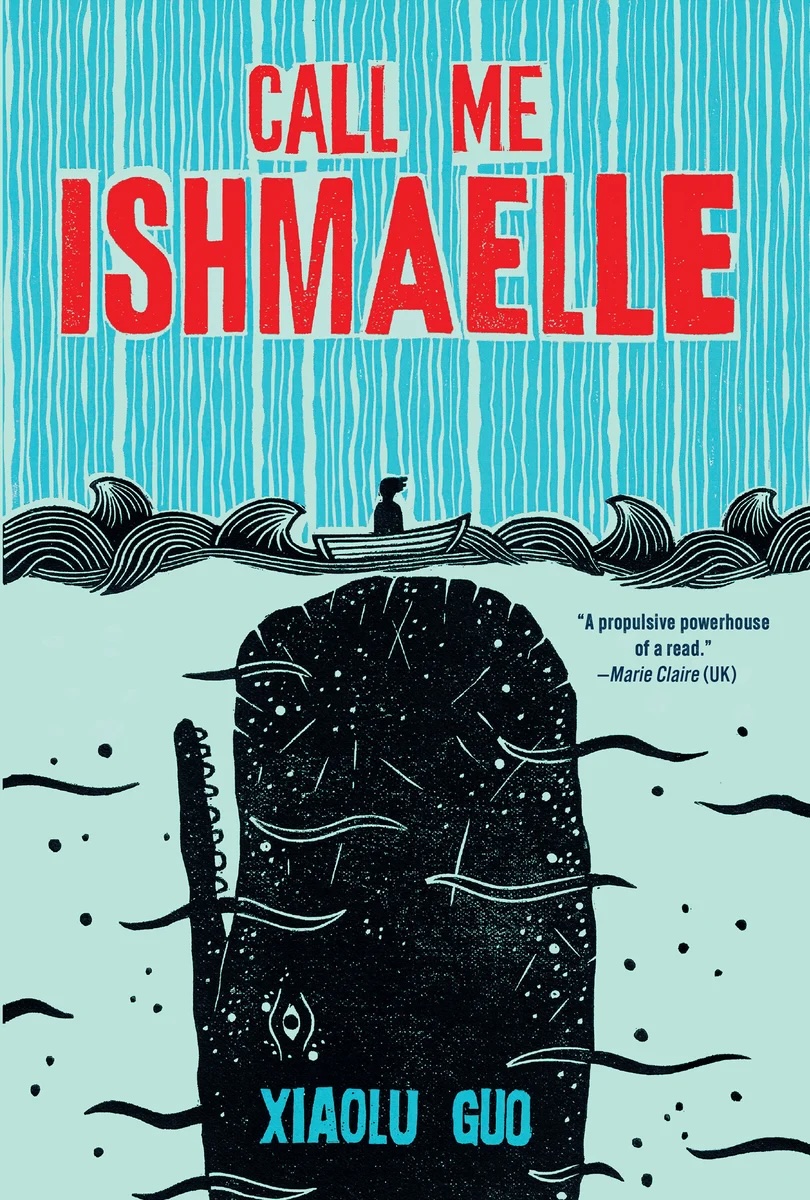

Call me Ishmaelle. But know that I have not always gone by this name. Names carry much power and in my own case that power has defined my story. It is a saga that begins and ends with the sea, and in the middle concerns a fantastical creature. I will need to tell it to you gradually. Some memories are as clear as day, others cloudy, and I must pause to recover them. I hope I will be true, both to what happened and to what I am. But first, the sea.

I was born in a windswept cottage on the coast of Kent in the year of 1843. It was the month of May, when the geraniums of our village graveyard burst into mauve and white blooms. That was an auspicious sign for a birth. But the night I was born there was a storm, and according to my mother, a great flock of seagulls hovered above our roof. They squawked and squealed, just as I did, a slimy wrinkled creature in my mother’s arms.

I grew up strong. I learned to walk like all children, but I also learned to swim. One summer, I remember the passing fin of a dolphin as I swam with my brother through the bay. That winter I watched grey seals and their pups, and I knew they came ashore to give birth on our beaches. During my early childhood, my brother and I lived in innocence, away from the great world, absorbed by sand, waves and marvels of the ocean.

In that great world, Queen Victoria sat on the throne of England. I knew nothing about kings and queens. But I remember when I was seven years old, my father told me that Queen Victoria was almost assassinated by an army officer! Miraculously, the queen survived and she managed to attend the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace the following year. I was very impressed by the idea of this woman king, who had already borne several children. I, who had never ventured beyond the coast of Kent, imagined within the plain stone walls of our house that I was Queen Victoria. I imagined the way she might walk and eat and talk. But, Ishmaelle, I told myself, you are too lowly to imagine a grand queen’s life. And it was true. The only rich person I knew was the foul-tempered butcher near our house who kept pigs, rabbits and chickens in his backyard.

We lived by the sea near Saxonham, on the salty fields of Denge Marsh. Saxonham was a village – not much more than a hamlet in truth – a few miles from Dungeness. Our cottage was surrounded by hard shingle and bitter eelgrass. God seemed to have forgotten us from the very beginning. The two front windows overlooked the beach. At the back of the house, in open fields, were three large windmills. They had been there for as long as I could remember. My father said one of the three was built by my grandfather with the help of the villagers. There were windmills all along the marshes stretching as far as the port town of Lydd, where goods and horses were sold at market. Those windmills stood on mud and marshes amid samphire and pink thrift flowers, the only warm glow around our house. They looked ghostly, especially at night, but they were full of life forms. Sea thrift loved to grow around their base in the spring. Then there were the robins and field puffins, they too liked to nest about the windmills.

When I was a young girl, I loved picking the white sea campions that grew on the coastal rocks. We called these flowers dead man’s bells, though they had another grisly name: witches’ thimbles. They grew on the edges of cliffs, and that was bad luck. Nothing should live on the edges of sea cliffs unless it is a sad barnacle or a fearful clam, my mother said. She told me that we should not pick white sea campions, otherwise some terrible disaster would befall us. But I did, in spring and summer. I picked them and made gallants and hung them around my neck. I hung them on our doorknobs too. I loved those little white creamy petals. Dead man’s bells, I heard the children sing. Dead man’s bells ring. One day, on the dock where my father worked as a carpenter, he vomited blood. A week later he was dead. He left behind my mother, my brother Joseph and my three-month-old sister who howled all day and all night. My poor mother had to work as a maid in the village. Every day, she left the crying baby with me and walked across the marsh to the village. I became a little witch. I stole potatoes and pig intestines from the butcher. I strolled to Saxonham and entered farmers’ houses to steal clothing while they were out milking cows. But a witch with witches’ thimbles was no good. I was a curse. I had toyed with fate, and disaster came.

__________________________________

From Call Me Ishmaelle by Xiaolu Guo. Run with the permission of the author, courtesy of Black Cat, an imprint of Grove Atlantic. Copyright (c) 2025 Xiaolu Guo.