Caleb Gayle on Reorienting the Reader

In Conversation with Mitzi Rapkin on the First Draft Podcast

First Draft: A Dialogue of Writing is a weekly show featuring in-depth interviews with fiction, nonfiction, essay writers, and poets, highlighting the voices of writers as they discuss their work, their craft, and the literary arts. Hosted by Mitzi Rapkin, First Draft celebrates creative writing and the individuals who are dedicated to bringing their carefully chosen words to print as well as the impact writers have on the world we live in.

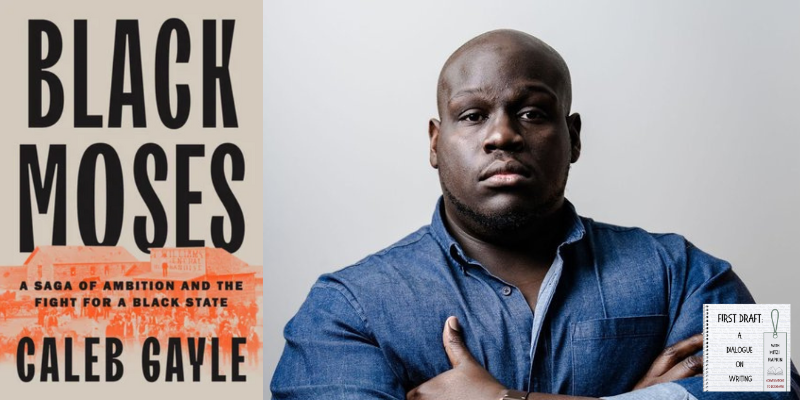

In this episode, Mitzi talks to Caleb Gayle about his new book, Black Moses.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

From the episode:

Mitzi Rapkin: In America, the terms were always changing at the time you’re writing about post-Civil War, because westward expansion was changing the landscape and Native Americans were being moved. But I felt, and you can correct me if I’m wrong, that when Edward McCabe started his dream of creating a Black state, there was a political openness to the potentiality of him actually, maybe succeeding in that dream. Whereas by the end of the book, as political fortunes changed, the white people passed more discriminatory laws and the general vibe was to limit the freedoms of Blacks again, and so the landscape really changed under his feet while he was doing this.

Caleb Gayle: I think you’re spot on. We have to kind of reorient the prospective reader, right? Civil War happened, emancipation happened, reconstruction had come and went. People weren’t leaving the South because of convenience. They were leaving because there was a significant resurgence of discriminatory practices, the formation of things like Jim Crow laws. So, it felt as if the West provided an opportunity. It provided the opportunity to allow your ambitions for equity and equality to flourish, and it appeared for a time, as the Oklahoma land runs made this place that was formally promised as the last time that the United States government would screw over very directly its indigenous populations and its indigenous nations. It was opened, and it seemed for a time that if you could get enough people who looked like you, under McCabe’s scheme, to move there, this could be it. This could be theirs. But as you mentioned, Oklahoma, like the whole of America, had become the South in that the very, very first laws, the very first law, Senate Bill number One, Oklahoma had just been established, it had become a state in 1907 and the very, very first law that was passed was a discriminatory law that said Black people and white people cannot occupy the same train car. That was the very first law. It also was the very first thing that launched McCabe into a very different posture realizing that his dreams of a Black state had ended that quickly. That he became, instead of a creator, an agitator, and what a worthy one at that who filed lawsuits, multiple ones in various courts that invariably led seven years later to his case being heard in the Supreme Courts, it’s where he flushed the last of his dollars from his various real estate endeavors fighting this case, suing one of the largest railroad companies in the world at that point, to try and get some level of equity, some meager breadcrumbs of equity in the state that he thought would be his. And so yes, as you mentioned, the grounds under his feet, the landscape of the American West turned from wide open plains, which it never was wide open plans to be very clear, right? There are many people in many traditions and many governance structures that long preceded them, but it instantly, in the course of a very short amount of years, became an opportunity to recreate some of the very horrors of the American South in the West. That was what made this place, Oklahoma, so interesting, because likewise, here today, we have many opportunities to try and recreate, reinvent ourselves into something a touch more inclusive. We have that choice almost every single day, in many ways, especially in this current political and social climate, all we’ve done is recreate and rehabitate and resituate a lot the most horrible things and then executed them upon the people who live here. So, I wish, admittedly, while writing it, that my story was a complete and total departure from the here and now. But in many cases, it resonates all too familiarly.

***

Caleb Gayle an award-winning journalist who writes about race and identity and is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine. His writing has been recognized by the Matthew Power Literary Reporting Award, the PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship, the Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellowship, the New America Fellowship, and a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, among others. In addition to writing, Gayle serves as an Associate Professor at Northeastern University. His nonfiction book is called Black Moses.

Memoir Nation

Memoir Nation: Weekly Inspiration for Writers is an extension of the Memoir Nation community hosted by Brooke Warner and Grant Faulkner, two friends and colleagues who bring a community-minded sensibility to the writing journey. Originally launched as Write-minded in 2018, this is a weekly writing podcast that focuses on memoir and personal writing, as well as industry trends and tips and resources for writers and authors.