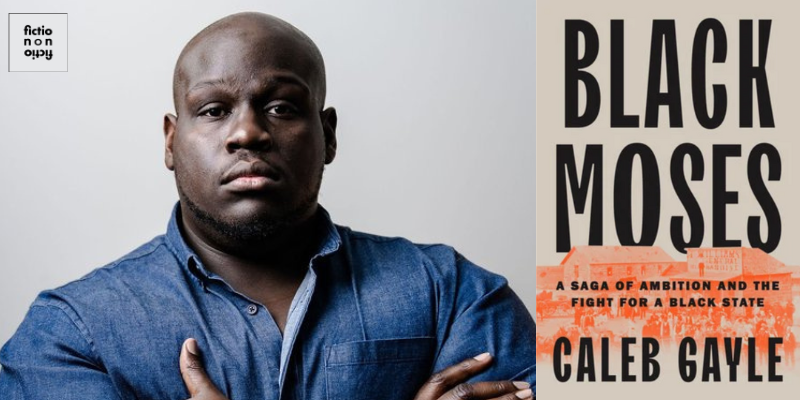

Caleb Gayle on Black Settlers in the American West

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Journalist Caleb Gayle joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new book Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State, which recounts the efforts of Edward McCabe, a Black settler who became a prominent politician in the late 1800s and spearheaded a mission to establish a majority-Black state in the American West. Gayle sets the scene of McCabe’s upbringing as a free Black man on the East Coast and his move across the country to majority-Black towns in Kansas and Oklahoma. Gayle also talks about how Black settlers navigated the challenges of the supposed promised land, including bleak weather and the machinations of white politicians. Despite great difficulties, Gayle explains, McCabe persisted, and while his dreamed-of state never came to fruition, his legacy is visible in some Western towns even today. Gayle reads from Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Moss Terrell.

Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State • We Refuse to Forget: A True Story of Black Creeks, American Identity, and Power • What Was the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921?

Others:

Victor LaValle’s Lone Women • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 6, Episode 25: “Alone on the Range: Victor LaValle on Lone Women’s Homesteaders, History, and Horror”

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH CALEB GAYLE

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So the “Black Moses” in your book is a man named Edward McCabe. We’re going to talk about what he did in the American West. But to start off, could you just tell our listeners who he was, where he was born, how he grew up and how he came up with the idea of creating Black-majority settlements in the American West?

Caleb Gayle: The best way to understand McCabe is that he was born in 1850. We have to remember and locate ourselves in time. This is 15 years before the Civil War ended. This is well over a dozen years before Black people are declared emancipated. But though he would eventually end up leading a lot of those people who were enslaved to a lot of these Black majority settlements that he’d found in the American West, he was born free. As far as we know, his parents were born free. He was born in Troy, New York. His childhood pastor was a guy named Henry Highland Garnet, this Black radical pastor who advocated for abolition and even made a young Frederick Douglass appear to be weak on matters of abolition and measures of equity. So McCabe was born there, but perhaps because he was born very distant from those who shared his skin tone—not dissimilar from Moses in the Bible, who was born with a certain level of privilege and access to proximity to power.

Whitney Terrell: Like he went to boarding school, didn’t he?

CG: He went to boarding school. He lived in parts of Newport and Bangor, Maine. It wasn’t until his father passed that he decided to join the working world. And he didn’t just join the working world as another guy. He was a clerk on Wall Street. He found that he was relatively encumbered by the limited opportunity set available to Black people, and moved to Chicago and became an advisor to the hotel king of State Street, Potter Palmer himself, who mentored people like Marshall Field, for those of your listeners old enough to remember what Marshall Field’s, the department store, actually was. But it wasn’t until McCabe partnered with a guy named A.T. Hall, Jr., and they endeavored to go to this place called Kansas, that at the time was about to become bursting at the seams with a lot of formerly enslaved Black people who were among the tens of thousands who had become quite convinced that yes, Reconstruction had ended. But the improvements, meager though they were during the Reconstruction era, had very much already started to fade, and many of their lives and opportunities were behind them. And so they went, initially to go to a place like Hodgeman to live pretty chill, normal lives, but they had a very interesting incident once they got to Kansas, specifically Lawrence, Kansas, where their plan shifted and they went to this tiny little town.

WT: I want to talk about that because I, as Sugi mentioned in the opening, live next door to Kansas, close enough that I just dropped my son off at the Shawnee Mission East soccer field to play soccer. You mentioned Shawnee in the book. A lot of the places that you talk about in the book are very familiar to me from growing up around here, including Nicodemus, which I’ve been to, and have heard about its history in different ways through my youth and growing up. But I did not know about Edward McCabe’s relationship to Nicodemus. So I wonder if you could talk about what that town is, how it came to be, and the role he played in making it what it would be.

CG: The best way to introduce it is to tell you that when a lady named Willina Smith was coming in from Tennessee, all of that way she looked out on the dusky plains in the 1870s and she said, “All I see are anthills.” She told her husband, “Where is this Nicodemus place?” And he was like, “Oh, that’s Nicodemus.” And she recalls for the record that “I began to cry.” Again, McCabe and his best friend A.T. Hall, Jr. weren’t planning to go there.

WT: It’s a small town in northwestern Kansas, in the middle of nowhere. It is bleak country up there, man.

CG: And it was even more bleak because getting timber for homes was a much fancier affair than they could afford, and that logistically they could make happen. So people were living in sod houses made of limestone and dirt and all sorts of things that they could find, right? But that’s where, in many cases, I think McCabe saw his opportunity. The town was a mess. It was askew. It was founded a couple of years before by a Black man named W.R. Hill and a white guy named W.H. Smith. They decided to found that town then move on quickly to the next one, because Nicodemus didn’t have as much to offer.

WT: I don’t want to bury the lede here. This is a Black-majority town that was founded by these exodusters, basically people leaving. Am I correct in all this so far?

CG: So it was initially founded by a handful of Black, formerly enslaved men who weren’t a part of the exoduster movement—the exoduster movement started a couple of years thereafter—and a white guy who was a train agent—a guy who would identify which tracks to lay, where depots lay, where—named W.R. Hill and he quickly left. He decided that this wasn’t for him and created his own town called Hill City, which, oddly enough, ended up having depots, opportunities, better schooling, better everything, incidentally. And so it was this Black town that was really laying fallow that people like McCabe ended up running. The fact that it was fallow allowed someone like a McCabe, a relative outsider, to emerge as this larger than life figure and lead the town that, at that point, was being run by a guy who was nefarious, to say the least, who had been pardoned for a murder and would go on to commit many other crimes. So that’s the moment in which we find it, but it became a magnet for hundreds and hundreds of Black people who were escaping the downfall of Reconstruction in the South.

WT: Which brings us to the term that I used earlier, exodusters, which is not a term that I had known, actually, before reading your book. So I wonder if you could define that for our readers and explain their role here in this story.

CG: Exodusters were people who saw the opportunity to escape from the American south—Black people, in particular, formerly enslaved people—into the American West. And what is a bit different about them, versus, say, people who were a part of the Great Migration, which would take place from 1910 to 1970 was that these people were going, in many cases, suddenly, to found something. They were there to create, to erect towns and townships, and they were attracted by people who would offer the clear stakes. It was Ku Klux or Kansas, right? It was either remain in the squalor of racial hatred that you’re sitting under, the racial bulldozing, or come into the West, which could perhaps even be pitched to them as somewhat of an Eden.

WT: I just want to say a couple of things, having driven so many times through Hayes, Kansas in the winter, going to ski or I’ve done a lot of hunting around Junction City. You talk about the wind. The wind in the wintertime, in Hayes drives you insane. They were living in these dugouts, which is why, as you point out, because tents would blow over. The conditions were just really rough. It was hard for me to imagine.

CG: When you read some of their oral histories and records, they were not only plagued but the winds also would carry tons of dust and dust would also carry lots of insects. So there are these harrowing efforts every single time they’d walk into the house to strip themselves of their clothes, hop on top of a chair, shake themselves off of the dust, the soot and the bugs, and then quickly hop into bed so as to ensure that the bugs wouldn’t fly with them, right? It’s not just founding, it’s not just escaping. They took on the veneer of the Exodus in the Bible, in part because it wasn’t clear that they had made it to a promised land, but they definitely knew very much about the wilderness.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Caleb Gayle by Jeremy Castro.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.