“But the Ancient Greeks Didn’t *Sound* Irish...” On Capturing Voice in Historical Fiction

Ferdia Lennon Considers the Role of Speech and Dialect in Bringing the Distant Past to Life

Almost exactly ten years ago, I sat in a writers’ workshop in the east of England and awaited my classmates’ verdict on what would become the opening of my debut novel, Glorious Exploits. For a long time, no one said anything. Finally, a student coughed and raised their hand.

“I’m a little confused as to what exactly you’re trying to achieve here,” he said, casting a quizzical frown at the manuscript he had annotated. So much red ink had been used to underline and cross out that the pages appeared bleeding.

“Sorry?” I asked, forcing a smile.

“Well, the ancient Greeks didn’t sound Irish.”

“But,” I sputtered. “How should a 5th-century BC Syracusan sound?”

“Well, certainly not like this,” he replied with an indulgent smile.

The problem of creating a voice that would, as far as possible, be accurate in spirit was very important to me.

A half hour or so later, I stepped out into the East Anglian drizzle, clutching my classmates’ notes, my head filled with the usual assembly of ripostes thought-up too late. However, along with this, was a genuine wonder at my classmate’s utter conviction. For him, he was just stating plain fact. Like saying the Arctic is cold, the sun rises in the east. The ancient Greeks didn’t sound Irish. In his mind, the Greeks of antiquity sounded, well, if you got down to it, probably a bit like him.

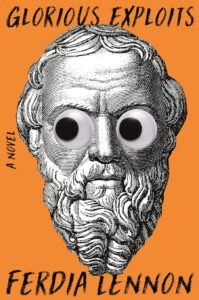

My debut novel, Glorious Exploits is narrated by an unemployed Syracusan potter by the name of Lampo who, along with his theater-obsessed best friend Gelon, sets out to put on Euripides’ Medea, with an all-star cast of Athenian prisoners of war who had, just recently, tried to conquer Syracuse. If you pick the book up—and here’s a piece of purely disinterested advice: You should—probably the first thing that will strike you is that Lampo speaks in a distinctly Irish voice. To be more specific, he sounds like a contemporary Dubliner.

I decided to do this for a few reasons. The first of these is concise: “Why not?” The convention of depicting the ancient world as populated by individuals who all sound oddly like the lords and ladies of Downtown Abbey is just that: a convention with very little holding it up beyond our sense that it feels right because it is familiar.

However, the reasoning behind my ancient Greek Dubliners went a bit deeper than “why not?” The Sicily of the 5th century BCE had been colonized a few hundred years previously by the city-states of mainland Greece. It struck me that the form of ancient Greek spoken in this colonial Sicily would probably have been a little different. When trying to find a way to render this difference, I didn’t have to look very far. Hiberno-English is English, but at a slant, with the influence of the native Irish language playing underneath and often lending a distinctiveness to certain turns of phrase.

What’s more, having characters from different parts of the ancient Greek world speak English in different accents—whether Irish, Scottish, Northern or Southern English, posh or working class—was also a way to convey that ancient Greece was not a privileged monoculture but instead was a tapestry of different classes, local cultures and identities with complex allegiances, rivalries and power relations.

Setting my story in a time and place where people spoke a now-dead foreign language gave me a great deal of freedom to explore what an ‘authentic’ voice in historical fiction might mean, a luxury not so easily afforded to writers depicting the English-speaking past. A writer who sets their works no further back than the 18th century has a reasonably straightforward task in that, with research, they can pretty faithfully recreate how the people of these periods expressed themselves, especially if those people were wealthy and literate. However, beyond this point, difficulties arise. You can write a novel set in Elizabethan London in early modern English. In fact, Anthony Burgess did just this in his brilliant story of Christopher Marlowe, Dead Man in Deptford, and yet even here, Burgess compromises accuracy for readability. Wanting to take it a step further, before his death, he was apparently in the midst of an epic about the Black Prince set during the Hundred Years War, all written in a kind of 14th-century Chaucerian English.

It was a way to approach the complexity of the past in an immediate and relatable way: to use the present to imagine what it felt to be alive then.

Perhaps luckily for me, accurately rendering ancient Syracusan Greek speech patterns was never conceivably an option. However, the problem of creating a voice that would, as far as possible, be accurate in spirit was very important to me. So, when I began to research Glorious Exploits, one of the things I tried to do was to completely immerse myself in what I called the ancient Greek mentality. Essentially, this amounted to reading every extant ancient Greek play, work of philosophy and history. I even read ancient Greek guidebooks, antiquity’s equivalent to The Lonely Planet, with descriptions of the best place to get a decent meal in Athens during tourist season.

What I was searching for was a sense of how these people saw the world. And still, in all of this, there was a glaring omission. Almost everything was written by the wealthy, for the wealthy, about things you could do only if you were wealthy. In a society where often half the population were enslaved, women were not citizens, and even the free male citizens were mostly of meagre means, the picture was madly incomplete.

As James Hynes, author of Sparrow, wrote when discussing anachronisms in historical fiction, there are no first-hand accounts of slavery from antiquity. Equally, there are no first-hand accounts of the lives of the ordinary working people of ancient Greece. Here, history, as so often happens, is eerily silent. Curiously, it is only in the raucous comedies of Aristophanes, himself a wealthy member of the Athenian elite, that the ordinary people of ancient Athens are given any semblance of a voice. These comedies are bawdy, sometimes surreal, sweary, crude and a world apart from the mythic heroes of the Greek tragedies or the rousing orations of famous statesmen that have formed the basis of so much of the Western world’s conception of high culture.

The fact that these were comedies meant that creating characters that the audience could recognize and have a good laugh at was much more important than following the formal rules that govern who should be depicted and how. The result is the exuberant, informal, unguarded, everyday speech of an ancient world teeming with colorful, messy, vibrant life that feels strikingly urgent. They are a slightly uncanny reminder of how the people of this period must have sounded to themselves: that is, contemporary. Reading Aristophanes, it struck me that, when it comes to bringing the past to life in fiction, just as important as the historical detail would be getting across the feeling that the characters, like us, are inhabiting their own present moment.

For me, this meant using contemporary accents, with all of their familiar connotations and implied social and political relationships, as an analogy that would give the reader a sense of who these characters were and their social relationships to one another. It was a way to approach the complexity of the past in an immediate and relatable way: to use the present to imagine what it felt to be alive then.

So, to my dear old classmate’s statement, “the ancient Greeks didn’t sound Irish,” I would add one last thing: they do now.

__________________________________

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon is available from Henry Holt and Co., an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Ferdia Lennon

Ferdia Lennon was born in Dublin to an Irish mother and Libyan father. He studied History and Classics at University College Dublin and holds an MA in Prose Fiction from the University of East Anglia. His short stories have appeared in publications such as The Irish Times and The Stinging Fly. In 2019 and 2021, he received Literature Bursary Awards from the Arts Council Ireland. After spending many years in Paris, he now lives in Norfolk, England with his wife and son.