“No Nights (or Chapters) Off.” And Other Grown Up Lessons From Reading to My Kids

Mark Cecil on What He’s Learned From the Toughest Audience There Is

There has been one single experience that taught me more about storytelling than anything else in my life: telling bedtime stories to my children.

Live audiences can be merciless; ask any comedian. Workshopping fiction can be rough, too. But I’d submit that while your own children won’t heckle you or carve up your prose with a snarky comment in the margin, they just may give you the most unvarnished feedback of all. Kids aged four to ten don’t have any agenda. They’re not competing with you, nor are they distracted. They’re just sitting right in front of you, all yours to entertain… or not. They don’t know how to pretend to like something, either. If they’re not pleased, you will know.

I should note that telling these bedtime stories was often excruciating for me. Story time happened around 9 PM, after a full day of work and driving my kids all over town to various events and practices. I’m a morning person, and I can assure you there was often an almost physical pain in dragging myself up off the couch to be creative in front of four expecting faces, late on a weekday night.

When writing a novel, I try to think of every chapter as like one night’s performance.Sometimes I made up a story on the spot out of whole cloth. Other times, we used prompts. Here was a typical one: each child would provide an element. Main Character? Spiderman. Place? School. Activity? Making brownies. Enemy? Sponge Bob Square Pants. From those disparate elements, I’d have to weave together a dynamic yarn of six or seven minutes, complete with an inciting incident, a climax and, on a good night, some moral to tie it all together, or even better, a cliffhanger to lead into the next night’s story.

If the story was going well, I’d see them watching me, happy and engaged. Sometimes they’d raise their hand with a question. But if I was bombing, hoo boy, I could just feel it. They’d fall asleep. They’d look away. Worst of all was the shame: they knew their dad was flailing, and they didn’t know how to help.

My kids have grown out of bedtime stories now, but I thought it might be good to consolidate all I learned from my years as a gladiator in that particular arena. Here’s a few of my best lessons from my time spent at the Bedtime University MFA:

Action, Goals, Obstacles, Resolution, Again (AGORA). At its heart, storytelling is pretty simple: begin with a character actively headed toward some goal. Then, throw an obstacle in their way. Then, have them deal with that obstacle, either through victory, defeat, or avoidance. Once the character comes to the end of that cycle, it repeats, with more actions toward goals with obstacles in the way. Other writers I know sometimes protest this formulation, saying that characters don’t need to want anything, or have goals, or face obstacles, or that the story doesn’t need a clear resolution. But I’ve found the safest bet is the ancient recipe. Meals need protein to be satisfying. AGORA is protein for storytellers.

Love And Conflict. On one particularly bad night, I wound my lackluster story down with a whimper. My seven-year-old daughter gave me a consolation hug afterwards. “What could I have done better?” I asked her. She answered with this timeless advice: “Every night, you need to have someone either falling in love or fighting.” There you have it, the two great engines of human drama—people moving toward each other in love, and people moving away from each other through conflict.

No Nights (or Chapters) Off. The stories I told my kids often lasted for just one night. Other times, and often due to popular request, a story would continue over many nights or even weeks, with cliffhangers strung along the way. But just because the story on a given night might be “merely” a piece of a larger tale, it still had to be entertaining and survive on its own merits. Each night’s installment had to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. It needed an attention-grabbing opening, swelling problems, a turning point, an edge-of-your-seat climax, and a denouement. When writing a novel, I try to think of every chapter as like one night’s performance. It can’t just be connective tissue between two other chapters; it has to deliver on its own.

Great stories are meant to be shared with others.Draft Without Anxiety. Writers are experts at finding reasons not to write. We make excuses like, “I’ll start writing after I’ve done a bit more research.” Or, “I’m just not feeling inspired. I’ll write when the mood strikes.” But when you’ve got kids ravenous for new material sitting in front of you, you just have to go with what you’ve got. Funny enough, I often found that when I winged it, I often came up with my best stuff. Perhaps the pressure woke something up in me. You can take a similar approach to drafting your more “serious” literary work: simply sit down at the computer and start writing, as if the audience was waiting for it, and you were abruptly shoved out on stage. You might be surprised by the results.

Revise Quickly and Without a Second Thought. Keep Only What Works. There are so many reasons people hold on to bad material: they worked really hard on it; a critique partner told them it was great; it fulfills this or that favorite theory of good storytelling; they did a ton of research on it. But in front of a live audience, the origin and rationale of your story simply do not matter. All that matters is if those eyes are locked on you. Are they paying attention, or not? Thus, be relentless and unsentimental in cutting boring or complicated material. The moment the story is flagging, just skip to anything that your audience seems to like. Don’t even question it. In front of my kids, I often would cut off a story midway and start in an entirely new direction. I’d go back to the last time they seemed to be paying attention and dig deeper there. I’d even steal material from another story, my own or someone else’s. Anything to keep them focused.

Stories Are a Communal Experience. Many people claim that they write just for themselves. Others experiment with “anti-stories,” or set out to challenge existing genres and even play games their readers. For me, great stories are meant to be shared with others. When my stories were really working for my kids, there was a kind of indescribable, timeless communion. It’s hard to explain, but after a performance really landed, it was as if we’d all gone through something rare, special, and even sacred together, as if I was teaching them something essential and profound about the grand, mysterious world that surrounds us.

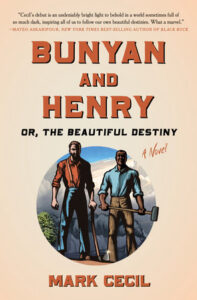

As it turns out, the most successful story I ever told to my kids was a retelling of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It was a month-long adventure tale, featuring American folklore heroes Paul Bunyan and John Henry, who filled in quite well for Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu in the original story. The kids loved it so much that they still remember bits and pieces of it years later, and can repeat parts of it back to me. After I finished telling the story, I got to thinking: maybe this could make a good novel for adults. So, I began writing.

I’m far from the only one who has workshopped material in this way. J.R.R. Tolkien was known for telling his kids stories, and his own children worked alongside him on some of his most famous works. Rick Riordan reportedly conceived of his Percy Jackson And The Olympians series as a bedtime story for his son, and William Goldman came up with The Princess Bride for his two young daughters.

My own book Bunyan and Henry; Or, The Beautiful Destiny, survived the most brutal and honest gauntlet of all. Anything that can keep my kids’ attention over the course of a month, well, it might just have a chance out in the world.

__________________________________

Bunyan and Henry; Or, the Beautiful Destiny by Mark Cecil is available from Pantheon Books, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.