Building a Better Definition of Science Fiction

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer on the History and Future of the Genre

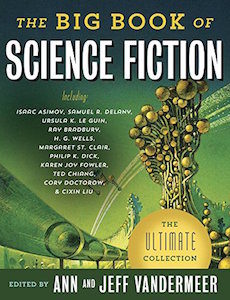

The following appears as part of the introduction to The Big Book of Science Fiction.

Mary Shelley, Jules Verne, and H. G. Wells. All three are useful entry points or origin points for science fiction because they do not exist so far back in time as to make direct influence seem ethereal or attenuated, they are still known in the modern era, and because the issues they dealt with permeate what we call the “genre” of science fiction even today.

We hesitate to invoke the slippery and preternatural word influence, because influence appears and disappears and reappears, sidles in and has many mysterious ways. It can be as simple yet profound as reading a text as a child and forgetting it, only to have it well up from the subconscious years later, or it can be a clear and all-consuming passion. At best we can say only that someone cannot be influenced by something not yet written or, in some cases, not yet translated. Or that influence may occur not when a work is published but when the writer enters the popular imagination—for example, as Wells did through Orson Welles’s infamous radio broadcast of War of the Worlds (1938) or, to be silly for a second, Mary Shelley through the movie Young Frankenstein (1974).

For this reason even wider claims of influence on science fiction, like writer and editor Lester del Rey’s assertion that the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh is the earliest written science fiction story, seem appropriative, beside the point, and an overreach for legitimacy more useful as a “tell” about the position of science fiction in the 1940s and 1950s in North America.

But we brought up our triumvirate because they represent different strands of science fiction. The earliest of these authors, Mary Shelley, and her Frankenstein (1818), ushered in a modern sensibility of ambivalence about the uses of technology and science while wedding the speculative to the horrific in a way reflected very early on in science fiction. The “mad scientist” trope runs rife through the pages of the science fiction pulps and even today in their modern equivalents. She also is an important figure for feminist SF.

Jules Verne, meanwhile, opened up lines of inquiry along more optimistic and hopeful lines. For all that Verne liked to create schematics and specific detail about his inventions— like the submarine in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870)—he was a very happy puppy who used his talents in the service of scientific romanticism, not “hard science fiction.”

H. G. Wells’s fiction was also dubbed “scientific romanticism” during his lifetime, but his work existed somewhere between these two foci. His most useful trait as the godfather of modern science fiction is the granularity of his writing. Because his view of the world existed at an intersection of sociology, politics, and technology, Wells was able to create complex geopolitical and social contexts for his fiction— indeed, after he abandoned science fiction, Wells’s later novels were those of a social realist, dealing with societal injustice, among other topics. He was able to quantify and fully realize extrapolations about the future and explore the iniquities of modern industrialization in his fiction.

The impulse to directly react to how industrialization has affected our lives occurs very early on in science fiction—for example, in Karl Hans Strobl’s cautionary factory tale “The Triumph of Mechanics” (1907) and even in the playful utopian visions of Paul Scheerbart, which often pushed back against bad elements of “modernization.” (For his optimism, Scheerbart perished in World War I, while Strobl’s “reward” was to fall for fascism and join the Nazi Party—in part, a kind of repudiation of the views expressed in “The Triumph . . .”)

Social and political issues also peer out from science fiction from the start, and not just in Wells’s work. Rokheya Shekhawat Hossain’s “Sultana’s Dream” (1905) is a potent feminist utopian vision. W. E. B. Du Bois’s “The Comet” (1920) isn’t just a story about an impending science-fictional catastrophe but also the start of a conversation about race relations and a proto-Afrofuturist tale. The previously untranslated Yem Zozulya’s “The Doom of Principal City” (1918) presages the atrocities perpetrated by the communism of the Soviet Union and highlights the underlying absurdities of certain ideological positions. (It’s perhaps telling that these early examples do not come from the American pulp SF tradition.)

This kind of eclectic stance also suggests a simple yet effective definition for science fiction: it depicts the future, whether in a stylized or realistic manner. There is no other definitional barrier to identifying science fiction unless you are intent on defending some particular territory. Science fiction lives in the future, whether that future exists ten seconds from the Now or whether in a story someone builds a time machine a century hence in order to travel back into the past. It is science fiction whether the future is phantasmagorical and surreal or nailed down using the rivets and technical jargon of “hard science fiction.” A story is also science fiction whether the story in question is, in fact, extrapolation about the future or using the future to comment on the past or present.

Thinking about science fiction in this way delinks the actual content or “experience” delivered by science fiction from the commodification of that genre by the marketplace. It does not privilege the dominant mode that originated with the pulps over other forms. But neither does it privilege those other manifestations over the dominant mode. Further, this definition eliminates or bypasses the idea of a “turf war” between genre and the mainstream, between commercial and literary, and invalidates the (weird, ignorant snobbery of) tribalism that occurs on one side of the divide and the faux snobbery (ironically based on ignorance) that sometimes manifests on the other.

Wrote the brilliant editor Judith Merril in the seventh annual edition of The Year’s Best S-F (1963), out of frustration:

“But that’s not science fiction . . . !” Even my best friends (to invert a paraphrase) keep telling me: That’s not science fiction! Sometimes they mean it couldn’t be s-f, because it’s good. Sometimes it couldn’t be because it’s not about spaceships or time machines. (Religion or politics or psychology isn’t science fiction—is it?) Sometimes (because some of my best friends are s-f fans) they mean it’s not really science fiction—just fantasy or satire or something like that. On the whole, I think I am very patient. I generally manage to explain again, just a little wearily, what the “S-F” in the title of this book means, and what science fiction is, and why the one contains the other, without being constrained by it. But it does strain my patience when the exclamation is compounded to mean, “Surely you don’t mean to use that? That’s not science fiction!”—about a first-rate piece of the honest thing.

Standing on either side of this debate is corrosive—detrimental to the study and celebration of science fiction; all it does is sidetrack discussion or analysis, which devolves into SF/ not SF or intrinsically valuable/not valuable. And, for the general reader weary of anthologies prefaced by a series of “inside baseball” remarks, our definition hopefully lessens your future burden of reading these words.

From The Big Book of Science Fiction by Jeff and Ann VanderMeer. Used with permission from Vintage Books. Copyright © Jeff and Ann VanderMeer, 2016.

Feature image: detail from “Horizons” a mural by Robert McCall.

Jeff VanderMeer and Ann VanderMeer

Jeff VanderMeer's most recent fiction is the NYT-bestselling Southern Reach trilogy. He is married to Ann VanderMeer, who has won numerous awards for her editing work, including the Hugo Award and World Fantasy Award.