Bringing the War Home: How Tim O'Brien Approached the Art of Moral Consequence

Alex Vernon on the Emergence of One of America's Early Literary Voices of the Vietnam War

How rich. John Wayne, the hero of so many rah-rah war movies including The Green Berets (1968) handed the 1979 Academy Award for Best Picture to Michael Cimino for his disturbing 1978 treatment of the war in Viet Nam, The Deer Hunter. It and Hal Ashby’s film Coming Home, starring anti-war activist Jane Fonda, dominated the awards that April night. Released in February 1978, Going After Cacciato hit the scene when U.S. audiences were ready to have the war turned into fiction, winning the National Book Award two weeks after the 1979 Oscars. Coppola’s Apocalypse Now came out in August. Each in its own way, the films and the novel, departed from strict realism and dealt with the question of leaving the war behind.

Reviews of Cacciato split over two issues. First, the success of the Paris pursuit fantasy and its integration with the war stories. Second, the novel’s apparent indebtedness to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. The pursuit daydream was deemed either a failure that broke its own spell and detracted from the war story, or a bold experiment that faltered at times but deserved celebration, or an astonishing and original accomplishment. The Catch-22 comparison is more flummoxing.

O’Brien has recognized the possibility of unconscious echoes of other works in one’s own….All literature is derivative to some extent, but originality can still obtain.

O’Brien did not complain in any extant letters when Gene Lyons’s preview in The Nation, based on the published excerpts, said that “O’Brien has chosen to write about Vietnam from the point at which Yossarian left off.” At the end of Catch-22, Yossarian has learned that his buddy Orr intentionally downed his plane and rafted to Sweden, out of the war. Yossarian plans to make a run for Sweden too, and barely escapes a stabbing on his way out the door, not unlike Cacciato’s slipping through the squad’s armed assault. “You’ll never make it,” Major Danby tells Yossarian. “It’s almost a geographical impossibility.” Cacciato physically resembles Orr, a “grinning lark” with a “deranged and galvanic giggle” who with his “raw bulgy face” was “one of the most homeliest freaks Yossarian had ever encountered.” O’Brien did not complain when his Bread Loaf friend Geoffrey Wolff or anyone else made the positive comparison. He did complain, however, about a publisher’s advertisement that began, in large type, GOING AFTER CACCIATO. PRONOUNCE IT “CATCH OTTO.” AS IN CATCH-22.

One can imagine the angry phone call O’Brien placed to Lawrence over the liberty with his title. He liked the sound of Cacciato, borrowed from his LZ Gator boss; he liked learning that it means hunted or caught in Italian. As he wrote Lawrence, “my main concern is that it not appear that I’m an imitator of Heller’s book. Much as I like it, and respect it, I certainly was not trying to write anything of the sort, and, in fact, I doubt that Cacciato even resembles ‘Catch-22.”‘ Heller’s novel was knee-slapping, O’Brien’s bluntly serious. For the rest of his life, O’Brien has insisted his novel did not intentionally take up where Heller’s left off. Neither he nor Hansen remembers Catch-22 entering their conversations about the novel in progress.

One could be forgiven for disagreeing. Paul Berlin “would look out to sea and imagine using it as a means of escape-stocking Oscar’s raft with plenty of rations and foul-weather gear and drinking water.” The squad fishes in Oscar’s raft; Orr fishes in his raft as he practices his escape, with “that goofy giggle of his and that crazy grin.” Goofy-smiling Cacciato fishes in bomb craters before his desertion. It’s not as if O’Brien never mentioned Heller in letters to Hansen, and there’s the Fort Lewis letter to Gayle Roby that used Orr to signal O’Brien’s intention to desert. Sam Lawrence connected the two novels in a letter to Billy Abrahams.

O’Brien has recognized the possibility of unconscious echoes of other works in one’s own. His effort to distance his work from Heller’s is understandable. All literature is derivative to some extent, but originality can still obtain. In quashing that advertisement, O’Brien wanted to preempt negative comparisons such as Christopher Lehmann-Haupt’s in The New York Times:

[B]y repeatedly evoking “Catch-22” Mr. O’Brien reminds us that Mr. Heller caught the madness of war better, if only because the logic of “Catch-22” is consistently surrealistic and doesn’t try to mix in fantasies that depend on their believability to sustain. I can even imagine it being said that “Going After Cacciato” is the “Catch-22” of Vietnam. The trouble is, “Catch-22” is the “Catch-22” of Vietnam.

Not to worry, as The New York Times Book Review lauded the novel on its front page and didn’t cite Heller. It did bring in Hemingway, as did John Updike’s review in The New Yorker, which struck the opposite note as Lehmann-Haupt’s: “As a fictional portrait of this war, ‘Going After Cacciato’ is hard to fault, and will be hard to better.”

Cacciato enjoyed plenty of glowing reviews, yet Updike’s review had a huge impact on its success and helped convince the reading world to pay attention to the literature of O’Brien’s war. As O’Brien’s agent’s office wrote to Lawrence, “The John Updike review in The New Yorker seemed to be the word that tipped the scales against resistance to a Viet Nam novel, and now all the scouts are asking for it.”

*

O’Brien wrote a few articles and book reviews in the wake of Cacciato. He liked the exposure and the money. It flattered him to be asked. For the moment, he had time. The reviews say as much about O’Brien as they do their subjects. He never wrote reviews again, because he learned that with literary friends and peers, even a good review might prove ticklish.

O’Brien trounced Vance Bourjaily’s A Game Men Play for its moral pointlessness. Craig Nova’s Incandescence fared better but fell short in “psychological insight.” Nadine Gordimer’s July’s People achieved in both the moral and psychological fields, although its difficult prose sometimes irritated. Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s otherwise smart Rough Strife suffered from the first-person narrator’s self-analysis eclipsing action and drive. Raymond Carver’s “splendid” collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love actively engaged “moral aboutness,” although the minimalism went too far. There’s nothing but praise for O’Brien’s friend Geoffrey Wolff’s The Duke of Deception: Memories of My Father and for Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song. Mailer’s hefty book, about the life and relatively recent notorious trial and execution of the murderer Gary Gilmore, amazed O’Brien, for whom the nonfiction or fiction label didn’t “matter a whit: The book’s effect is stunningly novelistic.”

Wouldn’t you know it, with Barry Hannah’s wild ride Airships, O’Brien judged its war stories the collection’s best because “War is a mix of the absurd and the deadly real.” James Jones’s posthumous Whistle could have used some imagination in trying for an original approach to a war story—the contrast with Cacciato is loud and clear. To O’Brien, Whistle’s four World War II veterans became indistinguishable; the novel contributed to the impression that all veterans struggle to readjust. The review flipped the received wisdom contrasting the untroubled generation of Jones’s war with the troubled one of O’Brien’s.

In the late 1970s, the plight of Viet Nam veterans was once again topical, and not just because of Hollywood. In his first official act as president, Jimmy Carter appointed the first Viet Nam veteran to head the Veterans Administration. Max Cleland was thirty-four years old, an ex-infantry officer who had lost both legs and one arm to a grenade. In his December 1979 Esquire essay “The Violent Vet,” O’Brien interviewed Cleland as well as other major voices and critiqued the myths of their war’s veterans as violent, incarcerated, drug-addicted, not honorably discharged, unemployed, and unwelcomed home. There was no hard data to support the stereotypes, O’Brien argued, and the available evidence suggested that the veterans of his war were no more likely to suffer these conditions than veterans of America’s previous two wars. Because in the end, the experience is essentially the same. Rifles and mud and army BS. But the country needed “the image of a suffering and troubled veteran” of Viet Nam:

Rather than face our own culpabilities, we shove them off onto ex GIs and let them suffer for us. Rather than relive old tragedies, rather than confront our own frustrations and puzzlements about the war, we take comfort in the image of a bleary-eyed veteran carrying all that emotional baggage for us.

Anne Mollegen Smith had left Redhook to lead Your Place, a new bi monthly for twenty-somethings, which ran O’Brien’s “Vietnam: Now Playing at Your Local Theater” in August 1978 (and listed him as a contributing editor). That essay begins with O’Brien recollecting his Worthington boyhood: “With my buddies beside me, I stormed the D-Day beaches of Lake Okabena—splashing, stumbling, firing from the hip. […] Lord, I was some fine soldier. I was a bloody hero.” But he wasn’t playing soldier. He was playing a movie star playing a soldier. And in Viet Nam, he watched real soldiers playing movie stars playing soldiers. The first story that found its way into The Things They Carried, “The Ghost Soldiers,” Esquire published not too long after the article, in 1981; it recycles the article’s language about soldiers playing action heroes in war movies. In 1986, O’Brien’s second Esquire story for the eventual book—its title story—depicts soldiering as an act of imagination, of pretending.

O’Brien’s gushing review of Scott Spencer’s Endless Love anticipated his future explorations of obsessive male romantic love. The things some men do. Spencer’s novel opens after the young narrator has torched the home of his ex-girlfriend’s family, an act that lands him in a mental ward. For O’Brien, “love, no matter how obsessive, is not merely destructive, and Spencer avoids such simplistic moralizing.” O’Brien’s takeaway was that “so-called ‘normal life’ with its ‘normal’ kinds of loving (affection, security, comfort, tenderness) seems dull and empty in contrast to the enormously heart-quickening, gut-thumping powers of true passion.”

O’Brien’s first piece in Your Place appeared in its inaugural issue. The O’Briens had very nearly bought the condo they’d been renting—”Fear of Buying” is about that moment in a young marriage when the couple realizes it’s time to give up the nomadic rental life and settle into a normal life of affection, security, comfort, and tenderness. Ouch.

*

O’Brien had begun casting about for ideas for his next novel while finishing Going After Cacciato. He was tired of writing about war, and he needed the advance.

The first idea merged his predilection for movement across landscapes with the autobiographical. As proposed to Lawrence in December 1976, “The Hunt” was to be about Ben Garrett, a sixty-year-old who joins a two week hunt into the South Dakota Badlands for the wolves stealing his small town’s sheep, only to find himself hunted by…someone. The man’s searching his past for clues would have given O’Brien a vehicle for working with his father’s past, as Ben Garrett and Bill O’Brien shared a Brooklyn Catholic boyhood, hotel work in the Bahamas, navy service during the war, moving to the Midwest for his new bride, then living a benumbed, normal life there as an insurance salesman for thirty years. O’Brien imagined a crisp, short, chapterless novel. Garrett will win the “brute” climactic battle but never learn the answers: Who was hunting him, and why? The novel would provide psychological insight without plot explanation or resolution—a narrative idea not realized until In the Lake of the Woods (1994). Six months later and Cacciato put to bed, O’Brien scrapped “The Hunt” for “The Sweetheart Mountains,” a love story between two old people. A month later the idea shifted. The same character, “around sixty-five, who fights the aging process by body-building and daily exercise,” is married. The Sweetheart Mountains were to be a fictionalized version of the Black Hills, so that O’Brien could freely invent without fussing over maps and histories. He fancied a straightforward first-person story that didn’t worry itself about themes or moral aboutness. The style was proving difficult—lyrical, future tense, direct address:

Let me go to the Sweetheart Mountains. Let it be autumn. Let me wake early, before your dog, and let me curl against you as I do. Breathe softly. If l should kiss you, don’t stir. Sleep with your wrist against your ear, listening to your blood as I have so often listened to your heart. Be silent. Through your dreams let me hear our house. Let me remember how we built it, board by board, squaring the rooms, our lives, you with a hammer and me with a saw.

After a page and a half, he knew he couldn’t sustain it. He taped a piece of paper on the wall behind his typewriter: “JUST TELL THE DAMN STORY.”

The nuclear threat mattered more than anything else of its era and seemed tailor-made for a writer concerned about…art of moral consequence.

At Bread Loaf in August 1977, he didn’t do a reading. By December, he’d chucked it all and started again. Three months later he’d been reading about the eventual end of the universe in a second Big Bang and began thinking about dramatizing “the linkage between man’s own mortality and the mortality of nature.” The story shifted again, its protagonist now “a seventy-year-old rancher out in the Dakotas whose land is bought up to put in Minuteman silos.” Not wanting to live at ground zero for Soviet missiles, and failing to stop construction, “he finally rides out on his horse to blow the whole business up.”

In September 1978, after his third Bread Loaf conference, O’Brien headed to Rock, Kansas, and McConnell Air Force Base, outside Wichita; to Little Rock, Arkansas; and to New York City to investigate America’s nuclear arsenal. He sought the physical “impressions of life at a missile site.” He wanted to touch a missile, literally “to touch the nuclear age.” The nuclear apocalypse terrified O’Brien, not just his own end but civilization’s. The Kansas farmers flabbergasted him with their nonchalance. “Look, we’ve all got to die somehow,” one of them harrumphed. O’Brien never found the silo outside town. The storms rolling in across western Kansas, and the deserted streets of Rock, felt as apocalyptic as O’Brien’s subject.

Gene Lyons, the Arkansas writer who had previewed Going After Cacciato, put O’Brien in touch with a former Titan II crew commander in Little Rock who hated his former job. That humanity had survived the early seventies struck the silo veteran as something of a miracle. “During my last night on duty, I climbed up to the highest part of that silo, aimed at the missile, and took myself a good, long piss.” Besides helping toward the potential novel, the fall’s research resulted in an article, “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” in Feature (January 1979).

In November 1978, O’Brien was back to the old man from “The Sweetheart Mountains.” He had merged the two ideas of the old man fighting death and fighting silos into a single book. In early October he had read a piece called “The Nuclear Age” at Middlebury College, which appears to have been a discrete story for an imagined collection about living in the Cold War inspired partly (if not wholly) by the trip for Feature. Instead the story became the germ for another novel.

By March 1979, O’Brien had written what at the time was the new book’s first chapter, “The Nuclear Age”—probably a developed version of what he’d read at Middlebury—and had placed it with The Atlantic Monthly (June 1979). He was working on both “The Sweetheart Mountains” and the new one, called The Nuclear Age. He was 120 pages into “The Sweetheart Mountains,” but the new idea excited him more. The writing was looser, more spontaneous. He predicted it would be his first blockbuster, and he was aiming for a film adaptation.

O’Brien pitched The Nuclear Age as the novel of his generation, and also a “bizarre” novel:

Sarah’s swiping a nuclear warhead from the Air Force; William’s subsequent caretakership of the warhead, traveling about the country in search of his two lost loves, the warhead covered up by a blanket in the back of his VW van. But these things, [though] bizarre, though funny, though a little absurd, are also fully compatible with the crazy times we live in: witness the SLA, witness terrorism, witness the nuclear mishap in Pennsylvania recently, witness the SALT talks, all that. Crazy, maybe, but not that crazy.

There’s a touch of Catch-22 in the sanity conundrum. Who’s crazy, the guy building a fallout shelter or everyone else, putzing along as if all were normal, the apocalypse not a button-push away? O’Brien fills the final novel with national and global news, from the Cuban Missile Crisis and the St. Paul anti-war march to President Carter’s pardon for draft dodgers. Several characters die in a scene very like the televised 1974 shootout be tween the Los Angeles Police Department and the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a far-left revolutionary terrorist group.

By May 1979, O’Brien had a two-book contract. Two books about the Cold War. The nuclear threat mattered more than anything else of its era and seemed tailor-made for a writer concerned about characters confronting mortality, about people caught in history’s currents, about art of moral consequence.

__________________________________

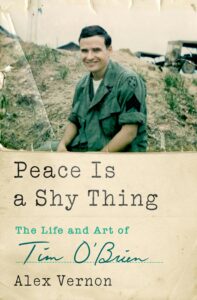

From Peace Is a Shy Thing: The Life and Art of Tim O’Brien by Alex Vernon. Copyright © 2025. Available from St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Alex Vernon

From Prairie Village, Kansas, Alex Vernon graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (the only literature major in his class of over a thousand), served in combat as a tank platoon leader in the Persian Gulf War, and earned a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. The recipient of an Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Book Award and a National Endowment of the Humanities Fellowship, he is the M.E. & Ima Graves Peace Distinguished Professor of English at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas. This is his eleventh book.