Bringing Felice Bauer to Life in Magdaléna Platzová’s Life After Kafka

Alex Zucker on the Importance of Style and Voice in Literary Translation

Magdaléna Platzová’s Life After Kafka, the second novel of hers I’ve translated, is a tour de force of structure, carrying readers across space and time: from central Europe to western Europe, the US west coast to the US east coast; from before World War II to after the war, through the 1960s and up to the present day. This peregrination happens by way of the author’s characters as well as the author herself, who is an integral part of the story, not only through her reflections on the life of Felice Bauer, but also through her personal encounters with Felice’s descendants, including Felice’s son and granddaughter.

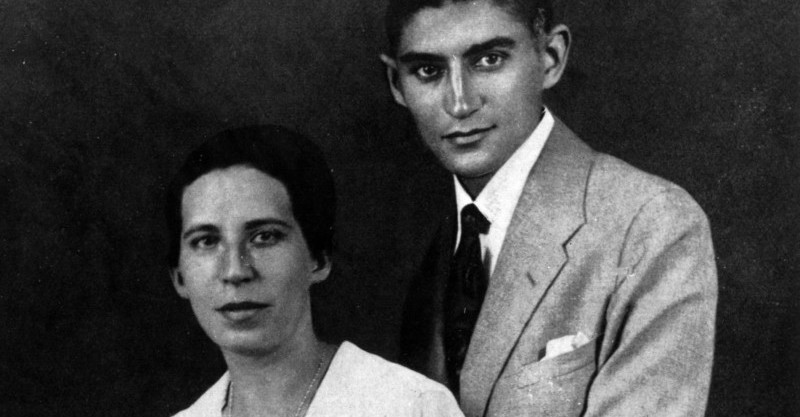

For most readers, the main attraction of this book, I expect, will be its limelighting of a woman who up until now has remained almost wholly in the shadows of a man who is one of the best-known writers ever. The voice of Felice Bauer—“a woman with a raucous laugh and a taste for bourgeois comforts”—was therefore, inevitably, the foundation of my translation.

The first scene in which we “hear” Felice Bauer speak takes place in 1935, in Geneva. Felice and her husband and children, along with her sister and cousin, have moved there from Berlin, as the first stop on their escape from Europe, where, with the Nazis’ 1933 rise to power in Germany, “the ground was disappearing underneath the Jews’ feet.”

Literary translation perforce involves interpretation. A literary text is a work of imagination in the language it was written.

Felice is entertaining her best friend, Grete Bloch, and another old friend from Berlin. Joachim, still a schoolboy, is bored with the adults’ conversation, irritated by Grete, and tries to sneak out of the apartment without his mother noticing.

As he walks out the front door, he almost collides with his mother.

“Where do you think you’re going?’

“Can I go out for a while?”

“Don’t you have homework?”

“It isn’t due until Monday.”

Tobacco smoke wafts from the half-open door to the drawing room. With the sun shining from the west now, the colorful panes of glass have dimmed.

“Supper is at seven.”

“Can I eat at the Weinbergers’?”

“No.”

“Please, Mom? They invited me.”

“No, we have guests.”

“All right, Mom.”

In Czech, Felice asks her son simply, “Kam jdeš?” Most often I would translate this, equally simply, as “Where are you going?” However, in view of her characterization, not only by Platzová in this book, but also by Kafka himself, in his Letters to Felice (which are quoted in Life After Kafka), I decided to emphasize Felice’s no-nonsense attitude by upping the rhetorical ante. Joachim is thinking about going out—such nonsense when he has homework to do, not to mention the family has company. (Spoiler alert: He goes out anyway!)

The novel’s next chapter takes place in Paris, in 1938. Felice and her family made it out of Europe in 1935, and now live in Los Angeles. They are low on savings, and Felice is keeping the family afloat by giving massages and baking sweets. On a trip to Paris to seal a financial deal, her banker husband, Robert (in real life, Moritz), has a heart attack, so Felice boards a plane—rather than the cross-country train, far more affordable but under the circumstances far too slow—and goes to bring him back.

Meeting with Robert’s business partner in Paris, Felice learns of another acquaintance who happens to be in Paris, the physician and writer Dr. Weiss, i.e., Ernst Weiss, who treated Kafka and took Kafka’s side in his relationship with Felice. She gets the address of Dr. Weiss’s hotel from Robert’s associate and goes for a stroll with him in the Luxembourg Gardens.

As the two of them catch up on what various old friends are doing and their current situations, Dr. Weiss informs Felice that, 14 years now after he passed, Kafka’s writings have been translated into French and “It appears he’s going to be as famous as Brod predicted.” After Weiss expands on the details and notes the banning, and burning, of Kafka’s books in Germany, Felice replies:

“Já na minulost moc nevzpomínám,“ řekne Felice, „nemám na to kdy. Ani moc nečtu.”

The verb vzpomínat (in the infinitive) is most frequently translated into English as to remember, to recall, to recollect, to think back—and, in the nostalgic sense, to reminisce. These are all translations I typically use, and had Felice been speaking in the affirmative (grammatically, that is, without the ne)—e.g., „Já na minulost vzpomínám až moc často“—I might well have used the verb reminisce: “I reminisce about the past far too often.” In fact, in my first draft, when I tend to translate as fast as I can, without reflecting on every possible option, I did: “I don’t reminisce about the past much.” In my second draft, I changed it to “I don’t dwell much on the past,” and that’s how it remained:

“I don’t dwell much on the past,” says Felice. “I don’t have time. I don’t read much, either.”

As in the first example, I felt this better conveyed Felice’s no-nonsense personality and approach to life. To her, to remember the past, to spend time on it (spend, because to spend, as with money, is to no longer have), is impractical, given the exigencies of her day-to-day.

*

The challenge of translating voice is multiplied, or perhaps just interestingly complicated, when translating into English from another language the voice of a character who in real life spoke English. There are several such figures in Life After Kafka, some of them contemporary, some of them historical, and none of whom I had met.

When an author writes the voice of a character based on a real person they have met, as some of the characters in Life After Kafka are (Felice’s son, Henry, in particular, who appears in the novel under the name “Joachim”), they of course have the advantage of having heard the person speak. So even when Platzová was writing the voice of English-speaking characters in Czech, she could think back on how they sounded when she met them and have that in mind as she wrote, translating it, if you will, into Czech. I, on the other hand, was recreating their voice based on her “Czech translation of it”—bringing it back, if you will, into an English that may or may not have sounded the same as the English the person actually spoke. I did the best I could—and this is fiction, after all, not a legal transcript—based on my own imagining of the person, which was in turn based on the author’s description of them: their upbringing, education, how they dressed, moved, etc. At the end of the day, I could only ask the author (and I did), Is this what they actually sounded like? Is this the way they spoke?

In a scene where the author (or, to be accurate, the character of the author, representing her) visits Leah, Felice’s granddaughter, at her home in a Manhattan high-rise, Leah talks to the author about her grandmother on her mother’s side (as opposed to Felice, on her father’s side), saying, in part:

“Babička z matčiny strany,“ vyprávěla Leah, „přijela do Ameriky v sedmnácti letech, neuměla číst ani psát. […]”

“My grandmother on my mother’s side,” Leah told me, “came to America at age seventeen. Didn’t know how to read or write. […]”

You can see the Czech has only one sentence, while my translation has two. The Czech language, Czech literature, has what I call a higher tolerance for sentences that in English are either considered run-on or are just plain too hard to parse without being broken up. That aside, what I want to point out is how I left out the personal pronoun in the second sentence, not using “she.” In Czech it isn’t necessary to use a personal pronoun here, because the verb ending makes it clear that the subject in the second clause (“neuměla číst ani psát”) is the same as in the first (“Babička z matčiny strany…přijela do Ameriky v sedmnácti letech”). But my choice to leave it out in English represented my sense of how Leah was likely to speak—in light, again, of her background, her upbringing, and the social context of an informal meeting.

I can easily imagine going back and translating every book I’ve ever done differently the second time around.

Later in the novel, the author/character of the author takes a train up the Hudson from New York City to visit Henry, alias Joachim, and ask him about Felice. “What was she like as a woman? What kind of life did she lead?” After a brief and unrevealing conversation, Henry offers to show the author some family photographs. He makes some chitchat, referring to the senior living facility where he and his wife now live.

“It’s small,” said Henry. “We had a house with a garden, big plot of land, a pool. But we couldn’t keep up with the maintenance.”

Similar to my leaving out the pronoun in Leah’s utterance above, here I opted not to use an article before “big plot of land”—again, in Czech, there is no need for an article of any kind, whether direct or indirect (the or a)—as well as contractions, to help shape the reader’s view of the character as someone who although highly educated was not overly formal in his social interactions.

Then, in response to the author’s query as to whether or not he ever read Kafka’s books, Henry replies:

“Nedávají mi smysl. Působí depresivně. Byl to blázen, mešuge. Měl velký problém s otcem. Vlastně mě nezajímá.”

“They don’t make sense to me. I find them depressing. He was crazy, meshuggeneh. He had a major problem with his father. I’m really just not interested.”

Here my translation shapes the characterization of Henry in three ways: One, where the Czech has Henry saying Kafka’s books “come across as depressing,” without the use of a personal pronoun (though one could argue it’s suggested by the mi, “to me” in the first sentence), I personalize his statement to say “I find them depressing.” (I could also have written, a solution I might opt for if I had it to do over again, “They strike me as depressing.”) Two, where the author uses mešuge, a Czech spelling of meshugga or meshugge, meaning the same as the Czech word preceding it, blázen, I use meshuggeneh—not because it’s correct but because it’s the version I’ve heard most often used by people when they speak. And three, I have Henry describe Kafka’s problem with his father as major, rather than simply big, as velký might also be translated, again in order to make his character more down-to-earth, and, I might add, with the approval of the author, Magdaléna, who actually heard him speak.

*

It’s inevitable that a literary translator “adds themselves” to the works they translate. Otherwise we wouldn’t be having the discussion about AI that we’re having now. Literary translation perforce involves interpretation. A literary text is a work of imagination in the language it was written, so it is impossible to produce a version of it in another language without imagination. (Made clear in Czech, for that matter, by the fact that literary translation is often referred to as artistic—umělecký—translation.) When asked to explain my work as a literary translator, I start by saying the main thing I translate is style. Not words. Style. A text, unlike a film, cannot “show” anything without the intermediary of words, so how a person speaks, their style, their manner, of speaking, is obviously key to the creation or development of a character. My own ideas about style, like an author’s, may also change over time. I can easily imagine going back and translating every book I’ve ever done differently the second time around. To me, this is life.

__________________________________

Life After Kafka by Magdaléna Platzová, translated by Alex Zucker, is available from Bellevue Literary Press.

Alex Zucker

Alex Zucker's translations from Czech include novels by Magdaléna Platzová, Jáchym Topol, Bianca Bellová, Petra Hůlová, J. R. Pick, Tomáš Zmeškal, Josef Jedlička, Heda Margolius Kovály, Patrik Ouředník, and Miloslava Holubová. He has also Englished stories, plays, subtitles, young adult and children’s books, song lyrics, reportages, essays, poems, philosophy, art history, and an opera.