Brief Variations on the Writer's Life

Roger Rosenblatt Approaches the Writer's Task from Unexpected Angles

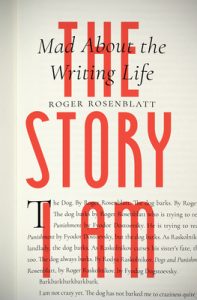

The following passages are from unpublished works by Roger Rosenblatt and appear in The Story I Am, available now from Turtle Point Press.

*

And do you know what’s really great about the imagination? I said. No, tell me, Dr. Watson. What’s really great about the imagination? Cait said, not even bothering to stifle a giggle of amused superiority. Well, I’m going to tell you, Holmes, you bitch. She laughed. The thing about the imagination is no one knows where it is located. No neuroscientist has the slightest idea where the imagination lives in the human brain. Mrs. Dwyer has this book about the brain, the areas of life it controls. Moving your limbs. Singing. Learning. Seeing. Hearing. All those functions, and more. Even loving.

Every one of our activities has a home in some particular area of the brain. Not the imagination. The scientists concede the imagination is real, but they haven’t found out where it lives. Most of them say it lives everywhere, in all the brain’s regions. You know what I say? No, Watson, what do you say? She hadn’t stopped smiling. I say the imagination is bigger than the human brain. It fills the universe. I say the imagination imagines itself.

*

The best days are the first to flee, said Virgil. But before they do. The birthday party when I was six, and, after blowing out the candles, singing every word of “Blue Skies” for my small, bewildered guests. At age four, sitting at the concert grand beside enormous Miss Jourdan, the editor and novelist who lived upstairs with Miss Prescott, the Columbia University librarian, and Miss Cutler, the ceramicist. Playing “The Blue Danube” and “Londonderry Aire” by ear. The ladies’ squeals of delight. Accompanying my dad on rounds, and winding up at the counter at the drugstore on Twentieth and Park, the two of us hunched over ham sandwiches and black-and-white sodas.

Tracking earthworms in the park. Riding an inner tube in Long Island Sound, straight to Portugal. Pears in a wooden crate. A horse’s neck, as he is about to take a jump. The sea captain’s house in Chatham, with the ship’s wheel in the living room. Snow piled like cake frosting on my bedroom windowsill. A road under a hard blue sky, and, though you cannot see it or smell the brine, the sea it leads to.

And my mother, having returned home from teaching junior high English in a school on Hester Street. And her mother, Sally, lounging around our gothic museum of an apartment in the late afternoons while I, the apple of their eyes, deployed brightly painted British soldiers in the Charge of the Light Brigade on the green bedroom carpet.

My mother teaches me to read. I am two and a half. We sit together at the dinette table with a book between us.

My grandmother, whom I called Giga, big face, black hair, singing “Look for the Silver Lining.” And my mother brandishing a shawl, strutting around the bedroom, like Mae West.

And my mother’s father, Joachim, whom I called Patta, getting off the Third Avenue El, and coming to our house from his sign-painter shop in the Bronx, and sitting at the end of my bed to tell me stories. I was five. And the night he sat there saying nothing, and I waited eagerly until finally he said in his pea-soup accent, “This time, you tell me a story, Raagh.” And I: “But, Patta, I don’t have a story to tell.” And he: “Tell me something you did today.”

So I told him about Mrs. Morris, who took a bunch of the neighborhood kids to Palisades Park that afternoon, and all the wonderful rides we went on, and the go-carts, and the Ferris wheel and the waterfall, and the little pond, which I stretched to the size of a lake, and the live alligator with two teeth, one gold, one silver, that chased me up a hill into a cave, where I hid beside a black bear, the two of us sitting very quietly, burying our faces in cardboard cones of cotton candy. And I saw Patta’s look of amused attentiveness, in which I also saw the power of words. And I loved what I saw.

*

My mother teaches me to read. I am two and a half. We sit together at the dinette table with a book between us. I remember nothing of that book, or of any of the others we read, but I still can feel her closeness, the fresh-roses smell of her clothing, and our intense conspiracy over words. In her early seventies until her death from Alzheimer’s years later, my mother will show only the look of fear. She will appear anxious even in death. But when I am little and she is in her mid-thirties, she is the face of serene competence. There is nothing she can’t do.

We make eggnog. She teaches me to stir the eggs and to pour in the vanilla. We sew on a button. We run the vacuum cleaner. We go shopping in the neighborhood. People acknowledge her and wave. She buys a baker’s dozen of cupcakes at the Gramercy Bakery and explains that a baker’s dozen mean 13. She takes me with her to the milliner. The shop is dead quiet, and the proprietor snooty. How do you like this one? my mother asks me, dramatically tilting what looks like a huge gray stuffed owl over her eyes. I giggle. We’ll take a baker’s dozen, she tells the milliner, who is unamused.

*

I am not quite three. My father isn’t home most Sunday mornings. He usually is on rounds. But today is an exception, and I am glad of it. I want to write a book. What’s the book about? he asks. I tell him I need his help, because the book will be about the heart, and I know he specializes in diseases of the chest. I also need his help because I know how to make only a few letters.

You dictate, he says, and then tells me what dictate means. I like the plan, and I start talking, as my father writes down my words. The heart has two parts, I say. The good part and the bad part. I go on to explain how each part evidences itself. I conclude that the good part of the heart always prevails. The words I dictate cover half a sheet of paper, which my father hands me.

Does the act of writing hold back the losses, cut the losses? Or does it make one more aware of what is being lost, of the process of loss itself?

You should keep this, he says. You wrote a book.

*

Black rain; a lifted latch; a clutch of goslings; sedge; smoke; slush; write it; a woman wades in wet grass, wipes muck from her ankles; lamplight exposes a shame; bluish slate and a dunghill (the smell, the smell); sand and silt and a slice of stone; earth-brown cobbles; fresh cream in a bucket; the slap of mackerel; write it; blood-tipped fingers; a grief, a gulf of darkness; boot prints in a riverbed, and burnt straw, and the red trail of a fox; a flutter of fish; who’s the drowned girl; a wheelbarrow avoids a traffic jam of sheep, and slips into the sluice; ghost-fog; lovers’ secrets divulged near a rusted anvil; harmonica music; and a red-eyed drunk stumbles down a footpath toward the skull of the sea; o beautiful girl; o beautiful glow-worm; a sow in the furrow; turf in the hearth (the smell, the smell); sunplay on cobwebs in a barn; a dog in the doldrums; a mouth full of sprigs; a burlap sack; a whip; drizzle on your face; a bike on its side in the weeds; mud on the handlebars; mud in your hair; mud in your eye; mud everywhere (the smell, the smell); write it, write it; the quilt; the face; the shroud.

*

Death means losing, in every way. Does it not? You lose your own life. You lose others. A guy dies. The doctor says, We lost him. Life means losing, too. You lose time, opportunity, poems. You lose poems. An Englishman named Empson wrote that. The dead fisherman was lost and remains lost. And the world goes on in a tacit, unconscious dirge in his honor. Fearing to lose all, Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus wrote his way out of sorrow.

Does the act of writing hold back the losses, cut the losses? Or does it make one more aware of what is being lost, of the process of loss itself? As soon as the thought becomes the word, you lose it. As soon as the word hits the paper, you lose it. Small wonder there is a feeling of dissatisfaction when one finishes a poem. Fearing to lose all, you lose all anyway.

*

Underneath his temperament, the pitcher is the team writer. You see it in the windup, when he’s about to toss the ball, and he pauses, stopped in air. At this moment, everything is possible. He addresses the batter as the writer addresses the blank sheet of paper. The ball will travel inside or outside, high or low, or down the center of the plate. It will be hit squarely, fouled off, or missed entirely. Any result may occur.

So the pitcher pauses on his perch and dreams of what he will write. And if a disaster ensues, and the ball goes sailing over the centerfield fence—if his writing falls flat in its face—he still has that one moment in the process, posed in his wind-up, when everything will turn out just as he has hoped.

__________________________________

Excerpts from The Story I Am: Mad About the Writing Life by Roger Rosenblatt. Copyright © 2020 by Roger Rosenblatt. Used by permission of Turtle Point Press, Inc.

Roger Rosenblatt

Roger Rosenblatt is the author of five New York Times Notable Books of the Year, and three Times bestsellers. He has written seven off-Broadway plays, and the movie adaptation of his bestselling novel, Lapham Rising, starring Frank Langella and Stockard Channing, is scheduled for release in 2020. His essays for Time magazine and the PBS NewsHour have won two George Polk Awards, the Peabody, and the Emmy, among others. In 2015, he won the Kenyon Review Award for Lifetime Literary Achievement. He held the Briggs-Copeland appointment in the teaching of writing at Harvard. He is Distinguished Professor of English and Writing at SUNY Stony Brook/Southampton.