Bridging the Gap Between My Two Cultures with Fictional Foods

Nikki May on Dreaming of Jam Tarts as a Child in Lagos

“They were all hungry at lunch-time. They went back up the cliff-path, hoping there would be lots to eat—and there was! Cold meat and salad, plum-pie and custard, and cheese afterwards. How the children tucked in.”

–From chapter four of Five On a Treasure Island by Enid Blyton

*Article continues after advertisement

I was seven-years old, living in Lagos, when I first discovered The Famous Five. Books were in short supply—there was only one bookshop and it specialized in academia, so you didn’t get to choose what you read, you grabbed any fiction you could lay your hands on. A friend had the complete set of the exceedingly popular Enid Blyton books. I borrowed them one by one and read them over and over. The stories were OK (I wished my parents were as hands-off as theirs), the characters were great (I liked Timmy the dog best). But it was the food that reeled me in. It was like being transported to another world, one I was desperate to be a part of. I curled my own tongue protectively into my mouth every time Dick tucked into a tongue sandwich. I dreamt of jam tarts—difficult when you’ve never eaten jam or seen a tart. My imagination had to a lot of heavy lifting. Even foods I knew, like boiled eggs, were rendered alien.

How could you eat lashings of boiled eggs? The word “lashings” was problematic; I hoped it was different to the beatings we got in school—corporal punishment was alive and kicking in 1970’s Lagos, it still is. These gaps in my knowledge made the reading more pleasurable, not less. Her books outlined the picture, but my creativity colored it in. The Famous Five’s stories became mine. They still are.

The fictional English food I consumed in literature as a child was so much tastier than the English food I consumed literally. My English mother was forever trying to recreate the dishes she loved, with varying degrees of failure. The ingredients she needed were unavailable and the alternatives were unsuitable—tinned margarine does not make a light and fluffy Victoria sandwich. Back then, I didn’t understand her desire for the food of home. Like everyone else, I was content eating stew twice a day, the only question was what to have it with—rice, yam, eba or dodo.

“Mushrooms!” my mother exclaimed on one of our Saturday forays to Leventis Stores, the Lebanese owned supermarket where expats shopped for packets and tins. Proper Lagosians went to the market for fresh, sometimes live, food. My mother clutched this miracle find to her chest like treasure. Her joy was infectious so my sister and I listened, eyes wide, mouths watering, as she described this magical ingredient.

“It’s savoury and meaty, deep and rich. You’ll love it,” she promised. “Nothing beats mushrooms on toast.”

We had to stop her there. What was toast? We didn’t have a toaster and even if we did, the erratic electricity supply would have rendered it useless. Her explanation made no sense. Why on earth would you want to make lovely soft bread go hard and crunchy?

Reading about English food as a child was a window into a world I was desperate to know more about.

Back at home, we crowded round for the great tin opening. Because of course the mushrooms weren’t fresh, this was Nigeria in 1972. Even hallowed Leventis Stores didn’t stretch to field mushrooms. We were severely disappointed at the slimy, limp slugs that she poured into a pan, shiny with viscous liquid. They tasted worse than they looked. Was all English food this awful? Were the Famous Five liars? ‘Can we have rice and stew?’ my sister and I asked in unison. I decided English food was best consumed in books.

Reading about English food as a child was a window into a world I was desperate to know more about. A strange land I was supposed to half belong to—I was half English after all. I’d been born there but my family had moved to Nigeria when I was two. When kids in school asked me what England was like, there was no way I was going to admit to not having a clue. So instead I told them about the England of Enid Blyton—my version, of course. Of things I’d never seen or tasted but which were alive in my head: picnics, elevenses and high tea. Ginger beer, dripping sandwiches, sausages, plum pie and custard. But after “mushroom gate” I began to want these mystical foods less.

I grew out of Blyton and into Agatha Christie. Hercule Poirot was clearly a smart man—he had his doubts about English cooking too. My food dreams evolved—I moved onto croissants, tisanes and pistachio and rose cake. I dreamt of eating an omelette aux champignons. Because I was eleven and hated French lessons, I had no idea champignons were mushrooms.

But fictional food doesn’t just anchor you to place, it’s a portal into a character’s soul. Poirot’s breakfast was as precise as his detective skills. Christie didn’t need to mention his OCD, describing his breakfast was more than enough. “Two symmetrical boiled eggs and a piece of toast cut into perfect squares, trimmed of crust.”

My early obsession with food in fiction has stood me in good stead. I have to know what my characters eat and how they feel about food. This matters just as much as (possibly more than) what they look like and how they sound. I insist on knowing every detail: Where do they buy their groceries? Do they cook on gas or electric? What are their favorite pizza toppings? Do they keep ketchup in the fridge or in the cupboard?

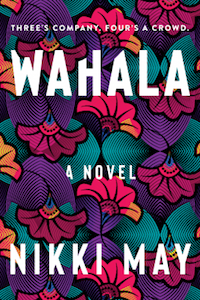

Far from being superfluous, these minutiae are what brought the women of Wahala—Ronke, Boo and Simi—to life. The facts may never actually appear in the book, but they matter to me. What we eat is one of our most important character traits and food is my way of making my characters truly authentic and distinct, it adds a rich layer to their personalities.

My early obsession with food in fiction has stood me in good stead. I have to know what my characters eat and how they feel about food.

Like so many things, food becomes more complicated when it’s refracted through a biracial lens. All the lead characters in my debut novel are mixed-race. They share the exact same racial mix—half Nigerian, half British—but they feel very differently about their heritage and what constitutes home. So of course, they feel very differently about food.

For Simi, it’s a way of showing off (she’d be first in the queue for overpriced kopi luwak coffee) and a way of demonstrating how in control she is (no carbs except in wine). For Boo, food is sustenance and cooking is a chore, something else to moan about. But for Ronke, Nigerian food is ritual, family treasure and a way of maintaining ancestral links and cultural connection. When Ronke makes moin-moin, a laborious multi-stage recipe, the process is sacred, the cooking itself is a comfort.

Comfort food is usually the food you ate as a child—first associations stick. For me, comfort food will always be Nigerian food. The word stew means completely different things to me and my (English) husband. He sees a dark brown rich sauce, carrots, onions, soft falling-apart beef, pillows of soft dumplings bobbing on the surface, a mound of mashed potatoes to eat it with. I see my grandmothers stew—red, oily and spicy. She’d give us one small piece of meat each (and we knew that was a privilege). The meat was tough and chewy (which is why teeth were invented), packed with flavor. It was saved to the end of the meal to be savored. Her stew was so good, all it needed was bread—soft, sweet, white Agege bread, to dip in it. Mama’s stews were lip-numbingly hot, she thought pepper made you strong. Maybe she was right; she lived to 102 and the average life expectancy in Nigeria is fifty-four.

Food has helped me cope with the space between my two cultures and find meaning in my in-between world. It’s an easy way to belong to two places even when you’re not fully accepted by either. Now I happily code-switch between my two cuisines. When it comes to food at any rate, two homes is twice the joy.

______________________________________________

Nikki May’s Wahala is available now via Custom House.

Nikki May

Born in Bristol and raised in Lagos, Nikki May is Anglo-Nigerian. At twenty, she dropped out of medical school, moved to London, and began a career in advertising, going on to run a successful agency. Her inspiration for Wahala came after a long (and loud) lunch with friends.