Breaking Through the Self-Mythologizing of the Male Artist as a Woman Biographer

Gabrielle Selz on Sam Francis and the Boy’s Club of the Art World

A man fell out of the sky, hibernated in a hard shell, then rose to become the painter of the heavens.

This story formed in my head when, at 10 years old, I first heard how Sam Francis became an artist. My father, an art historian and museum director, was organizing an exhibition of Sam’s art. In art world circles, Sam was famous as a globe-trotting artist, a man whose life was as immense as his paintings. Back in the late 1950s, his dazzling, color-saturated canvases, luminous continents of midnight blue, blood red, and lemon yellow surrounded by great slices of wide white sky, were more expensive than Picasso. Sam had told my dad that he’d never intended to be an artist. He wanted to become a doctor. But while training with the Army Air Corps in World War II, he crashed his plane and suffered a severe injury to his spine. Hospitalized for three years, encased in a full-body plaster cast, he taught himself to paint. From that moment on, Sam believed that flying led him to paint and that painting saved his life. Even as a child, I remember the wonderous feeling that this story conveyed. Like a figure out of legend, Sam soared, fell, suffered, and was reborn.

For over half a century, I never questioned this story. Neither did others. Sam told variations of it to everyone in his life: his studio assistants, gallerist, wives (he married five times), and his children. The story appeared in catalog essays and books. It is still up on Wikipedia. A dramatic event of a plane crash cleft Sam’s life in half, signaling the end of one existence and the beginning of another.

Looking at his paintings of boundless vistas of the heavens, the story made perfect sense.

Except that it never happened.

In 2014, when I began writing Sam’s biography, he had been dead for two decades, and neither I nor anyone else, had any idea that this story was a spectacular act of self-mythology. Like many, I’d been captivated by the epic nature of his narrative and how he channeled the physical act of flying into such pure expression in his art. He said he dreamed of trailing color across the heavens, then translated the limitlessness of sky onto the canvas. Embracing a peripatetic lifestyle, he circumnavigated the globe twice, assimilating and dispersing styles along the way. His expansive personality matched the grandeur of his mural-sized paintings.

But midway through my research, I realized I couldn’t make sense of his origin story. The accounts in interviews and art historical texts were vague and sometimes contradictory. He told my father that during flight training, his plane took a “strange twist,” and the injury to his back developed into spinal tuberculosis. He told the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard that he’d been seriously wounded in battle. And he told the art patron Betty Freedman that while flying a P-38, he ran out of fuel over the Arizona desert and injured his back in a fiery, emergency landing. Searching through his archives, the only accident report I found described how a gust of wind nosed over his propeller plane (not a P-38 Lightning) on the runway in Kansas (not the Arizona desert). Sam walked away from that tip-over without injury. Then too, I began to wonder, how exactly does one contract tuberculosis from an airplane accident? It is an infectious disease spawned by a bacterium that is usually inhaled. If left untreated, it can spread through the bloodstream into the spine.

Even Sam admitted in his journal writing, “I am a natural liar for I am an artist + naturally.”

By this time, I suspected the dubious nature of the airplane crash tale. One clue came from Sam’s lengthy correspondence with his high school sweetheart, Vera Miller, when he was in the Air Corps. Vera later became his first wife. He wrote about his various ailments: cough, flu, mumps, tooth abscess, fever, scoliosis, a virus, pneumonia, a bacterial infection, and finally, in November of 1944, “I have tuberculosis of the spine, and one vertebra is already diseased. I’m in a cast and can’t even rise out of bed.” He never once mentioned injuring his back, suffering a problematic landing or crashing his plane.

Still, even though I was doubtful, it was conceivable that both stories could be true: tuberculosis and the crash. Then, after a year of combing through his archives, I finally secured his hospital records. As I poured over the 400+ page document, I felt a wave of shock and amazement. My suspicion was confirmed. Sam had lied to everyone in his life for more than 50 years about his creation story. Though it was true that he suffered from life-threatening spinal tuberculosis and spent months wrapped in a body cast, he never crashed a plane.

I had uncovered the truth, and though I was thrilled with my discovery, I was infuriated with my unreliable subject. Sam had spun a captivating origin story, so perfectly allegorical no one thought to doubt it. I went back and questioned everyone I’d previously interviewed. To a person, they all gasped in disbelief then smiled in recognition. Of course, it was a lie, but why had none of us seen it before? Sam was no longer a man who crashed out of the sky, I marveled, he was a fabulist! He was a man with a long-buried secret. But what was obscured beneath the lie, and what did the lie, as well as the truth of his condition, reveal?

Sam was not alone in constructing a fundamental self-mythology. Many famous artists, reluctant to have the source of their creativity scrutinized too closely, have concealed, misdirected, and lied.

For two decades, Marcel Duchamp fooled the art world into thinking he’d given up art to play chess. After his death, it was discovered that all along, he’d quietly worked on his final great, enigmatic masterpiece, Étant Donnés. For the cerebral and ironic Duchamp, a lie was a contradiction, and a contradiction allowed him, he claimed, “to avoid conforming to my own tastes.” Chess, and the pipe he puffed while he played the game, was a smokescreen behind which he was free to create an installation piece—a tableau of a naked woman glimpsed through a peephole in a wooden door—radically different in appearance from his previous body of work.

Then there is the legend of Joseph Beuys, the German sculptor and performance artist. Like Sam, Beuys claimed that he survived a World War II airplane crash. Beuys said that he was a bomber pilot when his plane was shot down on the Crimean front. That he was rescued by Tartar shamans who rubbed his wounds with animal fat and wrapped him in felt. That they fed him milk and honey. In fact, Beuys was a radio operator (not a pilot) when his plane went down due to bad weather conditions (not gunfire). Shamans didn’t save him; Russian workers did. For Beuys, his life was a fable narrative, and as malleable and transformative as the art he created: paintings made out of honey, sculptures out of felt and milk bottles.

Frida Kahlo, too, conflated reality and fantasy to construct a persona that dovetailed with her art. She subtracted three years off her birth date, claiming to be born in 1910, the year of the outbreak of the Mexican revolution. As Mexico’s primary female artist, who donned and depicted herself in traditional Tehuana matriarchal costumes, she proudly linked her personal life and art with the birth and independence of her nation.

For Sam, lying was an early expressive act. In high school, he willingly abandoned the restrictions of truth for the sake of entertainment. In an apology note to Vera, he confessed, “I make up fictitious stories so that I can have a little word with you alone.” He distorted and exaggerated for dramatic effect—to win her interest. His stories operated much like a work of art does, as a charm that casts a spell, a fabrication that captures the viewer’s attention.

As Sam’s self-mythologies evolved, so did his artistic ambitions.

But it wasn’t until Sam left Vera, and America for France, five years after his hospitalization, that the crash story took flight. In France, Sam was free to create himself anew. Since he’d split from Vera, no one could refute his tale. He wanted to be seen as an American hero, not as an invalid. His narrative inflated from a “strange twist” in a trainer plane to a fiery crash in a P-38 Lightning in the desert. Elaborating further, Sam said that instead of bailing from the burning plane, he risked his life to land his valuable aircraft. That’s how he’d ended up in the hospital. Imperiling himself to save his plane.

Even Sam admitted in his journal writing, “I am a natural liar for I am an artist + naturally.” Like Kahlo and Beuys, he recognized the power of crafting a persona that fused his life and his art. Sam’s fictional airplane crash functioned both to mark the break from his previous life (his ambition to be a doctor) and to form a link to the artist he was becoming, a man who, having fallen from the sky, rose to paint the heavens.

As Sam’s self-mythologies evolved, so did his artistic ambitions.

Indeed, I now saw that for the purpose of my biography, Sam’s original lie, his self-creation myth, might be as telling as the truth. By constructing the crash narrative, Sam diverted attention away from the fact of his Tuberculosis. Surviving an airplane crash is a victorious and daring feat, and the accident itself has finality. It happens, and then it’s over. Tuberculosis lingers. In 1942, when Sam was diagnosed, there was no known cure. Tuberculosis was a life sentence. To be tubercular was to be weak, potentially contagious, isolated in a sanitorium. Although Sam was lucky enough to be one of the early patients to be treated with antibiotics and achieve recovery, the bacteria remained in his body and, 15 years later, reactivated and sickened him again. Sam did not want to be seen as feeble and withering. He wanted to be heroic, active, a life force. For Sam, his tuberculosis was the ever-present reminder that his life existed within the embrace of death.

Perhaps like Duchamp, Sam needed a buffer between himself and the world of factual truth. Again, in Sam’s writing, I found a clue to his thinking. “Telling a lie,” he explained, “is telling a truth about yourself.” Not only did the crash give Sam distance from his tuberculosis, it was a palpable connection to a very different accident that took place when he was a child. One that dramatically destabilized his life and one that, unlike the fictitious airplane accident, he rarely divulged. When he was thirteen, in an April Fool’s incident that went horribly, tragically awry, he accidentally shot and killed his best friend. Sam later claimed that the bullet that ended his friend’s life severed the boy’s spinal cord—in the same site as his tuberculosis. His story then allowed him to internalize his friend’s wound. Seen in this light, his airplane crash story makes heartbreaking sense. By adopting the persona of a pilot who crashed his plane and injured his back to save his aircraft, he refashioned his friend’s tragedy into an accident that hurt only himself. His lie allowed him to carry, for the rest of his life, the wound he’d inflicted on his friend.

Once Sam had obscured the truth, he was liberated to approach it in his art. To draw from life while simultaneously transforming it is at the very nature of creativity. His soaring paintings were born out of the conflation of fact and fiction, reality and fantasy, hubris and modesty. Though his work is often mammoth in size, they are delicately painted and constructed of the most basic, simple materials: paint and linen. His art, like his lies, were acts of conjoining the elemental and the sublime. But my job as his biographer was to untangle the web of myths and detail the facts. Yet I realized that the very same lies that fed Sam’s mythologies, and helped him identify a body of work, inspired the most unexpected revelations in his biography. Now when I look at his paintings, though I still see islands of color swimming in expanses of white space, I also see white as a void, representing the omnipresence of death surrounding all life’s colors. Ironically, it turns out that a lie is pretty honest and interesting frame to a true story.

________________________________________________________________

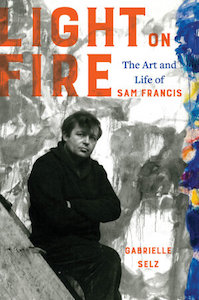

Gabrielle Selz’s Light on Fire: The Art and Life of Sam Francis is available now via University of California Press.

Gabrielle Selz

Gabrielle Selz is the award-winning author of Unstill Life: A Daughter’s Memoir of Art and Love in the Age of Abstraction. Her articles have appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times. Light on Fire: The Art and Life Sam Francis is her latest book.