“Chance of Rain”

The morning broke. Her husband stirred. The weight of the previous evening settled, the sullen dinner, conversations replayed in terse snippets as Bea examined the ceiling. The stillness of the house was like a museum after hours—something that had held life only hours earlier now inert. The air almost cool before the day’s assault.

She got up and dressed quietly and ran errands then drove to the home to visit her mother. It was one of the nice ones, for what it was. Her mother had her own apartment, though the kitchen was merely decorative; she could make tea and toast and that was about it. There was a dining room on the main floor. Two nurses lived on-site. It was bright, airy, unaffordable, difficult to get to, guilt-laden, and had an optimistic name—Galileo Sunrise. They all had optimistic names.

In the lobby a few women sat on a bench waiting to get picked up by dutiful middle-aged children. They were sweet-looking and silent, and Bea suddenly imagined them as teenagers at a dance somewhere, sitting in the postwar glow, waiting for shy boys to ask them to waltz. These women would be going to a nearby restaurant, catching up on grandchildren (all their achievements inflated—who was to know?). The dutiful daughter checking her phone when the mother went to the washroom, sending as many emails as possible before wondering if maybe she should go in there and see if anything had gone wrong.

And so much could go wrong. It was odd that at the age of forty-nine Bea was just beginning to understand that. That life was a long parade of unintended consequences. There was a moment in her thirties when she and her friends all seemed to be moving toward a fixed point. There was a linear quality to everyone’s lives; they bought houses, had children, renovated kitchens. But that sense of momentum had vanished. Her world now looked like the birth of the universe, random upheavals, black holes that sucked in the light, a loosely structured chaos that might produce anything.

Bea went up to her mother’s apartment and let herself in. Her mother was staring at the blank television screen, as if waiting for a picture. Always petite, she was further diminished now, her fine cheekbones still there, the only thing that prevented her face from collapsing. It was as if they held up her whole existence.

Bea’s sister lived in Chicago and so all the care duties fell to Bea. Ariel came to town three or four times a year for a testy three-day war on how their mother should be cared for, and Bea got to feel superior and resentful while Ariel (who was two years older) behaved like the managing director of Mother Inc.

Ariel, her mother said. It could rain.

I’m Beatrice, Mother. Ariel lives five hundred miles away. And it hasn’t rained in more than a month. It threatens to rain, then doesn’t. That’s why the city looks like the Kalahari Desert.

The girl on the weather—

The weather girl has been so wrong for so long it’s a miracle she has the nerve to show her face on TV.

But if it does—

It won’t, but if it does, we’ll find a café and have a tea.

I don’t like tea.

We’ll drink gin.

They went down in the elevator and in the lobby Bea signed out one of the wheelchairs.

Her mother could walk without it, but it was slow going. Easier to push her. She wheeled her mother outside, and within half a block sweat trickled down her spine. Her T-shirt began to cling. The park was five blocks away and by the time she got there, there were large dark blotches of perspiration.

How is Mrs Wheeler? Bea asked. She thought this was her name. A thin, slightly demented woman whom her mother sometimes ate with.

Alma? A bit bitey. She bit Mr Fetherling. They warned her.

She bit someone?

Not hard. Not a wound. I felt a drop. Did you feel something?

It’s not raining, Mother. Bea looked up. Those clouds hadn’t been there an hour ago. Bea wondered what they would do in the park. The Japanese flowering cherry trees had failed to blossom, an ominous sign in what was becoming a season of ominous signs.

We’ll go around the path, then maybe stop for tea, Bea said.

I don’t like tea.

Bea pushed her mother along the paved path, past geese and children and picnickers. The old-growth trees drooped above, light coming through in impressionist splashes. There were animals in cages along the steep hill, motionless in this heat, mounds of fur languishing in the shade. Bea had come here as a kid, before animal rights.

The light suddenly darkened. Bea looked up at the clouds, a midnight blue. The air changed, cooler, both welcome and menacing. There was a flash of lightning then crashing thunder, the kind that sounds as though it’s ten feet away. Bea looked up. It would open up any second.

That was thunder, her mother said helpfully.

Yes.

The café was about two hundred yards away. Bea turned back to head toward it, stepping up her pace. It was suddenly very dark.

I felt something, her mother said.

Bea was almost running now. Others were running, mothers with small children racing for their cars. Another crack of lightning. Bea half expected to see a tree fall across their path. The thunder roared.

Thunder, her mother said.

Then the deluge. They were soaked through in seconds. The rain coming down so hard she couldn’t hear what her mother was saying. The landscape was blurred and dark grey, her glasses useless. She picked up her pace, running as fast as she dared, pushing the wheelchair, which rattled over the paving stones. It hit something—a raised stone maybe—and the wheelchair turned violently to the left, tipping, her mother sprawling out onto the path with a small cry. Bea fell over the wheelchair awkwardly and felt something tear and landed hard on the stones. There was a sharp pain in her knee. She brought her hand to her face and tasted grit. It took a moment to orient herself. Her mother was lying on her back, her thin legs spread out, a child’s legs, the rain assaulting her face.

Mother.

Bea couldn’t tell if there was any sound coming from her. The rain hammered loudly.

Mother, are you all right?

Bea crawled toward her. Her mother was on her back, her face up, her mouth open, rain splashing in, coughing.

Oh god. Mother, here, we have to . . . She looked around. Could someone . . . There wasn’t anyone around them. The rain came down so hard it bounced. When the next crack of lightning came, Bea thought the earth would open up.

Jesus Jesus. Mother. Bea got up, hobbling slightly. There was blood on her knee, her pants torn, the red instantly diluted by the downpour. She got the wheelchair upright then went to her mother.

We need to get out of here. Mother, are you okay? Oh, please be okay.

A soft moan.

She tried to put her mother in the wheelchair, but as she bumped against it, the wheelchair moved backwards and she had her mother’s dead weight in her arms, bringing them both down. Her mother cried out in pain. The rain was violent, wrathful.

Are you okay? Where does it hurt?

Her mother didn’t say anything. Bea collected the wheelchair again. Her limbs were instantly weary, everything so wet and heavy. She looked around. She couldn’t see thirty feet. She found the brake on the wheelchair and pressed down on it. Her mother was lying on her back. She tried to lift her and couldn’t and dragged her the few feet. It took everything to lift her into the wheelchair. She almost slid out, but Bea grabbed her. Her mother cried out again, a yelp of pain, like an animal’s. Bea noticed her arm, bent at a slight but sickening angle.

Oh god. Mother. Your arm.

She searched for the seat belt they never used. Bea was crying now, in frustration as much as anything. She found the belt and fastened it with difficulty.

Hang on, we’ll get out of this. We will. Oh, I’m so sorry.

Bea pushed her quickly toward the café in the middle of the park. In the parking lot there were people sitting in their cars, engines on, wipers going. The rain coming down so hard. Some of the cars were trying to leave and no one could see and there was chaos in the lot. At the door of the café a man was waving people away.

Full, he said.

It’s an emergency, Bea said, checking for her cellphone.

The man wasn’t a man. Maybe sixteen, his first job. He quickly disappeared inside, looking for someone in charge. Bea found her cell and dialed 911 and asked for an ambulance. A few people huddled at the door looked at her mother and made sympathetic noises. Drenched, she looked even smaller, as if she would shrink to nothing, melt in the rain like the Wicked Witch.

Mother, I’m so so sorry, Bea said. She was crying harder, kneeling, looking into her mother’s eyes, which were blank. She might be in shock.

The ambulance arrived minutes later and had trouble navigating the crowded parking lot. It pulled up and two uniformed people got out. Bea approached them, pointed to her mother. There was a flurry of activity, moving her gently onto the stretcher, buckling the straps, wheeling an IV, then quiet, persistent questions that Bea answered as best she could. Was her mother on any medications, did she have any allergies? Bea climbed awkwardly into the ambulance. Someone folded up the wheelchair for her. She looked at her mother’s face, stricken, foreign-looking. One of the paramedics, an expressionless woman in her twenties, her hair soaked, sat beside Bea. The ambulance lurched through the city and Bea swayed with every turn. She looked down at her leg. One leg of her linen pants was torn at the knee. She put her fingers through the hole and touched the blood and brought it to her lips, grateful for the wound.

*

You almost fucking killed her!

This was three days later, Ariel on the phone. Their mother out of the hospital, back in her faux apartment, her arm in a sling. It sounds worse than it was.

It sounds like you almost killed her. My god, Bea, what the hell were you thinking? Do you know how serious a broken bone is at that age?

It was an accident, Air, we were trying to get out of the rain.

Why were you even in the rain in the first place? You take an eighty-six-year-old woman out for a walk in a thunderstorm?

Bea stared at a point on the counter that could have been a stain or an anomaly in the glazed limestone. She hadn’t noticed it before. It might be a tiny fossil, something ancient and extinct, an ice age catching it by surprise. She picked up her glass of wine then set it down again.

She listened to her sister vent for a bit. As a child Ariel memorized monologues from movies. She did an unnerving version of Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry and used to sneak up behind her and jab a ballpoint pen in her neck and deliver that soliloquy—Being as this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you’ve got to ask yourself one question: Do I feel lucky? Well, do ya, punk? And now every real-life rant sounded like a performance. It was a performance. Ariel had never stopped performing. She had difficulty distinguishing real life from film. Bea waited as long as she could before cutting her sister off.

Here’s an idea, Air: why don’t you spend three weeks researching assisted living residences, find one that takes people with mild dementia, has registered nurses and a doctor who didn’t get his degree from a Guatemalan website, employs two dozen minimum-wage Third World attendants who’ve been screened for al Qaeda connections, something within driving distance, which this doesn’t remotely qualify, and you—

Oh Christ, I don’t have to listen to this—

Go and see her six times (more like three) a week and ask how many people Mad Dog Wheeler has bitten then write a cheque for $5,200 every fucking month.

The fact is—

The fact is you wouldn’t get through the first week. This situation is ideal for you, Air, you get to give advice and keep five hundred miles between you and anything messy. When was the last time you emptied a bedpan?

What the hell are we paying $5,000 a month for—

We’re not. I am . . .

Bea had never actually emptied a bedpan. It bothered her that Ariel made her lie. And the money was coming out of their mother’s dwindling account, though Bea was managing it. Jesus, Bea, the money—

You’re sitting in another city doing what you do best—giving useless advice and not doing a bloody thing.

Bea punched the red button and ended the call. Her heart was racing. She picked up her wine and took a long sip. Well, family. There was nothing like it.

__________________________________

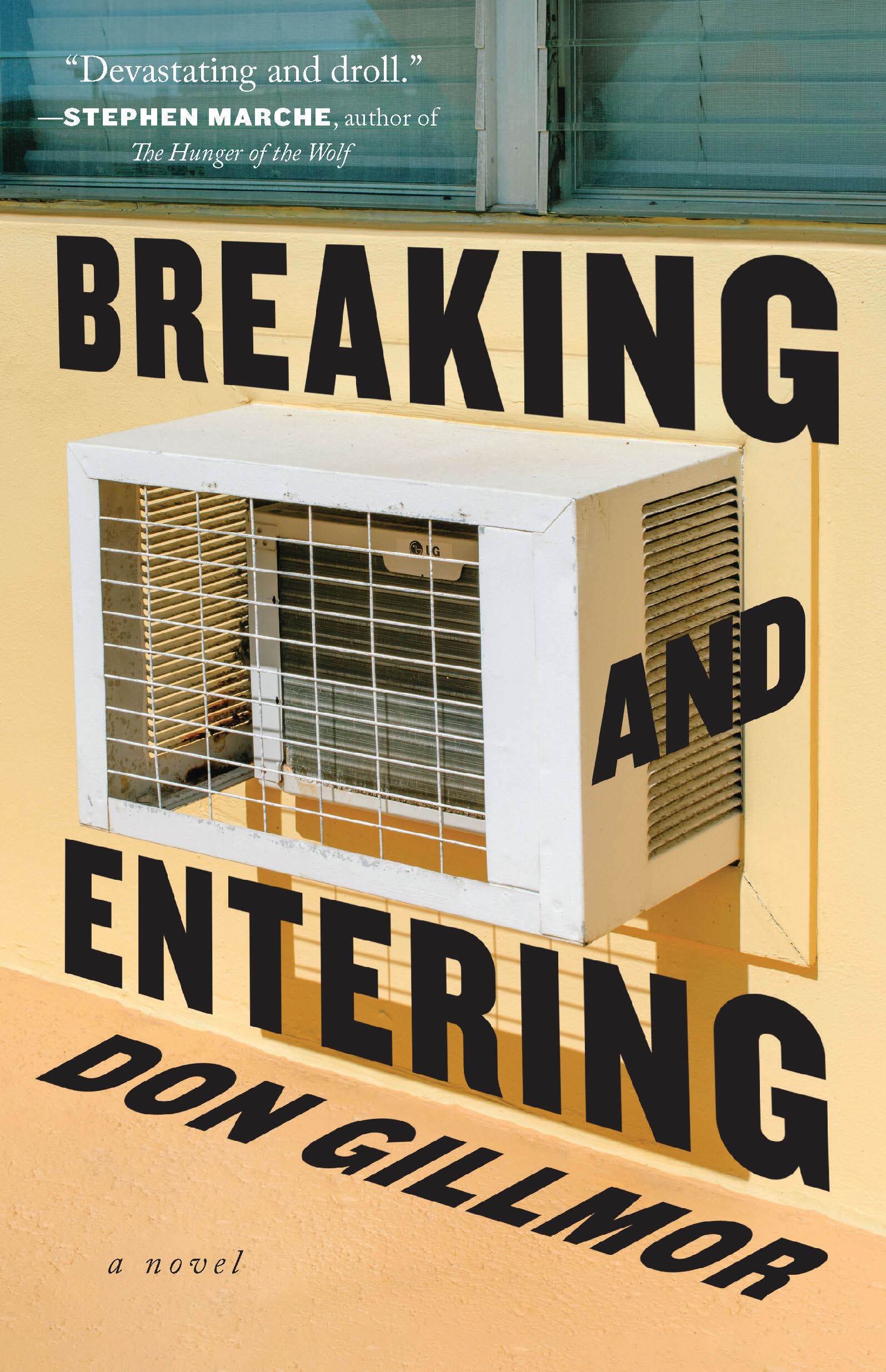

Excerpted from Breaking and Entering by Don Gillmor. Copyright © Don Gillmor, 2023. Excerpted with permission by Biblioasis. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.