Brazil’s History Is Ahead of It, Not Behind

Geovani Martins on Finding Joy in a Beautiful, Struggling Nation

The following pieces first appeared in Portuguese, in the Brazilian newspaper O Globo. Translated by Julia Sanches.

*

For the first time in my life, I went away on vacation. I spent entire days admiring the world, without any thought to day-to-day concerns. It was incredible. More than taking a break from work, it was like pressing pause on everyday life. Everything becomes more colorful and mysterious. But it’s hard for me to experience only pleasure in the Brazil of today. More than once, after discovering a new idyllic beach in the capital of Bahia, I felt the country crumbling around me.

This dichotomy isn’t new to me, unlike vacations. I remember the day I signed a contract with Companhia das Letras for my first book, and hours later had a gun pointed at my head. I also remember when the folks at the publishing house called to say they were commissioning translations of some of the stories because they thought the book might stand a chance of being published abroad. I’ll never forget that day, and everything that crossed my mind. Months earlier, I’d been working 12- to 13-hour days at a beach stand where I’d take shit from insufferable customers and see black kids getting beat up on a daily basis. I was so happy and restless after that phone call that I got up to walk around and, before I knew it—my house was small at the time—was in the kitchen. All of a sudden, I came face-to-face with an enormous rat that shot out of the room the moment it saw me. Which drew my attention to the dishes piling up in the sink: it’d been almost a week since we’d had any water in that part of Rocinha, the favela where I lived. That night, as I fell asleep, I wondered if I’d ever be able to spend an entire day just being happy.

A year later, I was given the chance to make a living off the work I loved doing, to travel the country talking about literature, sell translation rights to ten countries, as well as film rights, among other accomplishments. At the same time, I saw people close to me suffering. And I experienced my share of tragedies, on both the micro and macro level. 2018 was at once awful and wonderful. And I don’t just mean for me—I also watched as tons of brilliant people grew and carved out spaces for themselves. That’s the thing. One side of the coin is always covered in smiles, embraces, and amazing encounters.

Until this vacation, I think I was doing a decent job of keeping these extremes balanced within me. But that sweet tourist life—with moquecas and ice cream, beaches, sunshine, and endless laughter—was too stark a contrast to the misery screaming out from the city, just as it screams out from every city across the country. At times, I felt guilty for being happy, even though I knew it hadn’t been easy for me to reach the point I was at, where I could go on vacation, eat out at restaurants, and take cabs. But, whenever I saw a person who was visibly hungry, desperate, things stopped making sense for a moment, and I felt an ache in my chest.

In the midst of all this confusion, I attended a Zeca Pagodinho and Maria Bethânia concert. The packed venue sang “Santo Amaro à Xerem” as one, while women sambaed like there was no tomorrow, under a gorgeous night dotted with stars. Visibly affected, and with clenched fists, Maria Bethânia ended the concert by singing: viver e não ter a vergonha de ser feliz—to live and not feel ashamed of being happy. It was like she was speaking directly to me. Happiness is also resistance, she seemed to be saying with body and voice. Message received, I swear I’ll try, menina de olhos de Oyá.

–February 2, 2019

*

Before seeing the body on Avenida Rio Branco, I’d gone looking for some records. For a moment, as I shuffled past him and toward my destination, I saw a woman walking in the opposite direction and shaking her head like she was disappointed. I wasn’t exactly sure of what was happening, but her gesture caught my attention; a well-dressed and well-fed person had interacted, albeit negatively, with a homeless man.

I was walking down the same street with my shopping when I spotted a security guard from Centro Presente and several people milling around him. I immediately thought: someone’s taken a beating. But, no. It was the body of a man who, for all appearances, seemed to have died in his sleep in the city center. I immediately recalled the gesture the woman had directed at that man. Had she realized he was dead, or was she shaking her head at those living conditions?

I’m impressed and terrified by how deeply in conversation this modern phenomenon is with the history of Brazil, which has a habit of pushing things into oblivion, of leaving things unsaid . . ..Dying is painless, the scene seemed to say. It’s living that hurts. The man lying on the ground in the center of one of the largest cities in Brazil felt nothing. I drew closer. The security guard in charge of the situation seemed as lost and intrigued as the other passersby.

What will they do with the body, does he have a family, or not, is he going to end up in a niche, or will his corpse be studied at a public university? And what about the other bodies, the live ones all lying on that same strip of sidewalk? It was in the middle of this train of thought that I heard another onlooker say, as much to himself as to others: there’s no use hanging around now, no one seemed to care while he was alive.

I think of the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro. Of what we lost, of what we could go on to become. There’s no way to know, once this piece is published, whether the fire will still be a talking point in the media, in family conversations and bars, or whether it will have been subsumed by other events. Issues appear and disappear every day at frightening speeds. I’m impressed and terrified by how deeply in conversation this modern phenomenon is with the history of Brazil, which has a habit of pushing things into oblivion, of leaving things unsaid, of looking ahead without trying to figure out how we got here in the first place.

The thing is, our country’s history is imprinted on our sidewalks and prisons, in statistics and absences. And no social cleansing projects or assets-freezing for healthcare and education, nor any myths of racial democracy or extermination policies can erase it. On the contrary, the tension intensifies with every passing day. History, and we’ve seen enough to corroborate this, always takes its toll.

Before seeing that body, I had taken part in an event with the author Ana Maria Gonçalves. We were in conversation at Rio’s Museum of Art, on a panel about Black Cinema. By the end of the discussion, we had agreed that what we needed was more ruins, that only after we had razed the structures that held up the society of today would we witness the birth of something new. Outside, despite everything and everyone, the Museum of Tomorrow working perfectly. I don’t believe in coincidences. Now more than ever, I believe in Millôr Fernandes’s mantra, quoted by Ana at some point during our conversation: Brazil has a huge past ahead of it.

–August 15, 2018

*

My brother and I, plus a couple of local friends, were drinking beer at a bar in São Luís, in the northeast of Brazil, when a hippie started trying to sell us crafts, bracelets, necklaces, and pipes. After having a drink with us and insisting we accept a reggae bracelet in return for our company and beer, the hippie left. Soon after, Fábio, a friend my brother and I had made the day we arrived in the city, told us about the time a boa constrictor had fallen on that same hippie at the Reviver Market. I asked him how a boa constrictor had ended up there. According to Fábio, the constrictor lived in the shops’ tiled roof. I’d been to that market about three times since I’d arrived. Not putting much faith in his story, I asked our buddy Sorriso if he’d ever seen one. He said he’d seen loads, then explained that the merchants encouraged the constrictor to live there as a way to end to the proliferation of rats in the area. That night, I went to bed uncertain whether the two of them had been pulling my leg.

The next day, I went to the market, where I found a book stand. After buying a book, I asked the bookseller about the constrictor. With the same ease with which a person will drink a glass of water, the old man confirmed everything I’d heard the day before and added that the constrictor had migrated indoors because the rats had been wiped out. She’ll be back once they try and take over the market again, he concluded. I’m not sure if it was because of the fear he saw in my face or the nostalgia he felt while discussing that creature, but he made a point to say: constrictors are the most docile animals in the world.

The story of the constrictor stayed with me for the rest of the day. Everything took on a fantastical air. I’d been really impressed by that city. By the accent, the breeze, the way people thought and spoke of the world around them. When night fell, I saw that fear reversed as my brother and I told stories of shootings we’d witnessed in Rio, of the arrival of the UPP, the innerworkings of drug-trafficking. I realized that they were alarmed by stories that, though often shocking and revolting to us, we still discussed with some ease. They, too, were impressed by our accents, our expressions, by the way we saw and narrated the world around us. Our conversations were all marked by the cultural shock of our encounter.

After returning from São Luís I started thinking of how we Brazilians don’t even know our own country. Especially southerners born in Rio and São Paulo. Representations of Brazil are often centered around these two capitals, so we grow up with only a limited view of our country. Which is why we must be careful of the unusual patriotism growing stronger and stronger here by the day. In the end, what Brazil do these patriots plan to prioritize? In a continental country like our own, any exact definition of nationhood is futile. In the face of this fragmentation, only one possible patriotism exists: the one that vows to fight for the lives and rights of all Brazilians. Any patriotic ideal that doesn’t do so will never be more than just politicking and cliché.

–December 8, 2018

______________________________________

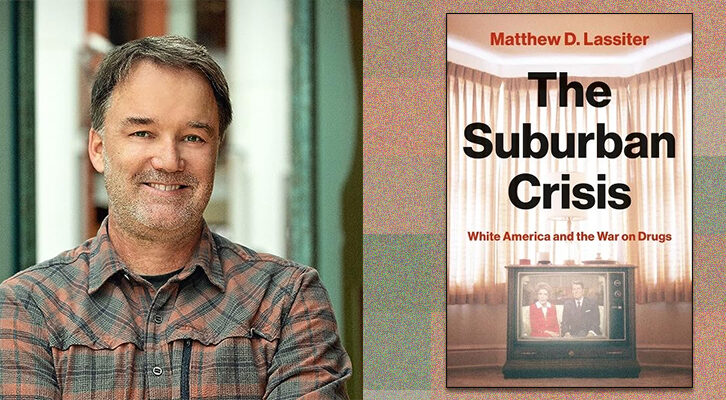

The Sun on My Head by Geovani Martins is out now from FSG.

Julia Sanches translates from Portuguese, Spanish, French, and Catalan. She has translated works by Susana Moreira Marques, Noemi Jaffe, Daniel Galera, Claudia Hernández, and Liliana Colanzi, among others. Her work has also appeared in Two Lines, Granta, Tin House, Words Without Borders, and Electric Literature. She is a founding member of the Cedilla & Co. translators’ collective, and currently lives in Providence, Rhode Island.