I found Borne on a sunny gunmetal day when the giant bear Mord came roving near our home. To me, Borne was just salvage at first. I didn’t know what Borne would mean to us.

I couldn’t know that he would change everything.

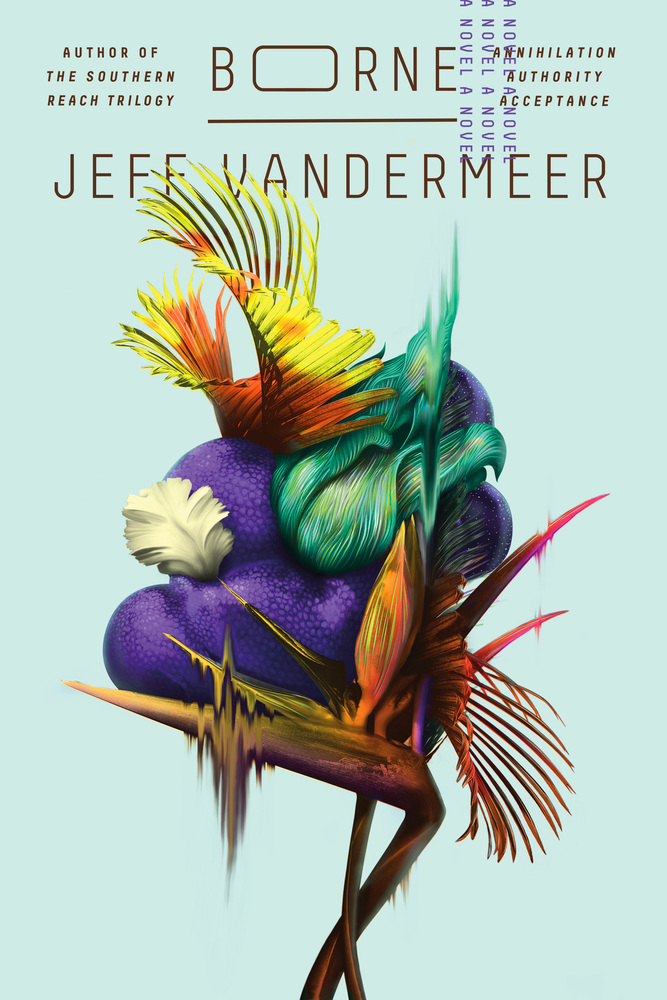

Borne was not much to look at that first time: dark purple and about the size of my fist, clinging to Mord’s fur like a half-closed stranded sea anemone. I found him only because, beacon-like, he strobed emerald green across the purple every half minute or so.

Come close, I could smell the brine, rising in a wave, and for a moment there was no ruined city around me, no search for food and water, no roving gangs and escaped, altered creatures of unknown origin or intent. No mutilated, burned bodies dangling from broken streetlamps.

Instead, for a dangerous moment, this thing I’d found was from the tidal pools of my youth, before I’d come to the city. I could smell the pressed-flower twist of the salt and feel the wind, knew the chill of the water rippling over my feet. The long hunt for sea-shells, the gruff sound of my father’s voice, the upward lilt of my mother’s. The honey warmth of the sand engulfing my feet as I looked toward the horizon and the white sails of ships that told of visitors from beyond our island. If I had ever lived on an island. If that had ever been true.

The sun above the carious yellow of one of Mord’s eyes.

* * * *

To find Borne, I had tracked Mord all morning, from the moment he had woken in the shadow of the Company building far to the south. The de facto ruler of our city had risen into the sky and come close to where I lay hidden, to slake his thirst by opening his great maw and scraping his muzzle across the polluted riverbed to the north. No one but Mord could drink from that river and live; the Company had made him that way. Then he sprang up into the blue again, a murderer light as a dandelion seed. When he found prey, a ways off to the east, under the scowl of rainless clouds, Mord dove from on high and relieved some screaming pieces of meat of their breath. Reduced them to a red mist, a roiling wave of the foulest breath imaginable. Sometimes the blood made him sneeze.

No one, not even Wick, knew why the Company hadn’t seen the day coming when Mord would transform from their watchdog to their doom—why they hadn’t tried to destroy Mord while they still held that power. Now it was too late, for not only had Mord become a behemoth, but, by some magic of engineering extorted from the Company, he had learned to levitate, to fly.

By the time I had reached Mord’s resting place, he shuddered in earthquake-like belches of uneasy sleep, his nearest haunch rising high above me. Even on his side, Mord rose three stories. He was drowsy from sated bloodlust; his thoughtless sprawl had leveled a building, and pieces of soft-brick rubble had mashed out to the sides, repurposed as Mord’s bed in slumber.

Mord had claws and fangs that could eviscerate, extinguish, quick as thought. His eyes, sometimes open even in dream, were vast, fly-encrusted beacons, spies for a mind that some believed worked on cosmic scales. But to me at his flanks, human flea, all he stood for was good scavenging. Mord destroyed and reimagined our broken city for reasons known only to him, yet he also replenished it in his thoughtless way.

When Mord wandered seething from the lair he had hollowed out in the wounded side of the Company building, all kinds of treasures became tangled in that ropy, dirt-bathed fur, foul with carrion and chemicals. He gifted us with packets of anonymous meat, surplus from the Company, and sometimes I would find the corpses of unrecognizable animals, their skulls burst from internal pressure, eyes bright and bulging. If we were lucky, some of these treasures would fall from him in a steady rain during his shambling walks or his glides high above, and then we did not have to clamber onto him. On the best yet worst days, we found the beetles you could put in your ear, like the ones made by my partner Wick. As with life generally, you never knew, and so you followed, head down in genuflection, hoping Mord would provide.

Some of these things may have been placed there purposeful, as Wick always warned me. They could be traps. They could be misdirection. But I knew traps. I set traps myself. Wick’s “Be careful” I ignored as he knew I would when I set out each morning. The risk I took, for my own survival, was to bring back what I found to Wick, so he could go through them like an oracle through entrails. Sometimes I thought Mord brought these things to us out of a broken sense of responsibility to us, his playthings, his torture dolls; other times that the Company had put him up to it.

Many a scavenger, surveying that very flank I now contemplated, had misjudged the depth of Mord’s sleep and found themselves lifted up and, unable to hold on, fallen to their death . . . Mord unaware as he glided like a boulder over his hunting preserve, this city that has not yet earned back its name. For these reasons, I did not risk much more than exploratory missions along Mord’s flank. Seether. Theeber. Mord. His names were many and often miraculous to those who uttered them aloud.

So did Mord truly sleep, or had he concocted a ruse in the spiraling toxic waste dump of his mind? Nothing that simple this time. Emboldened by Mord’s snores, which manifested as titanic tremors across the atlas of his body, I crept up farther on his haunch, while down below other scavengers used me as their canary. And there, entangled in the brown, coarse seaweed of Mord’s pelt, I stumbled upon Borne.

Borne lay softly humming to itself, the half-closed aperture at the top like a constantly dilating mouth, the spirals of flesh contracting, then expanding. “It” had not yet become “he.”

The closer I approached, the more Borne rose up through Mord’s fur, became more like a hybrid of sea anemone and squid: a sleek vase with rippling colors that strayed from purple toward deep blues and sea greens. Four vertical ridges slid up the sides of its warm and pulsating skin. The texture was as smooth as waterworn stone, if a bit rubbery. It smelled of beach reeds on lazy summer afternoons and, beneath the sea salt, of passionflowers. Much later, I realized it would have smelled different to someone else, might even have appeared in a different form.

It didn’t really look like food and it wasn’t a memory beetle, but it wasn’t trash, either, and so I picked it up anyway. I don’t think I could have stopped myself.

Around me, Mord’s body rose and fell with the tremors of his breathing, and I bent at the knees to keep my balance. Snoring and palsying in sleep, acting out a psychotic dreamsong. Those fascinating eyes—so wide and yellow-black, as pitted as meteors or the cracked dome of the observatory to the west—were tight-closed, his massive head extended without care for any danger well to the east.

And there was Borne, defenseless.

The other scavengers, many the friends of an uneasy truce, now advanced up the side of Mord, emboldened, risking the forest of his dirty, his holy fur. I hid my find under my baggy shirt rather than in my satchel so that as they overtook me they could not see it or easily steal it.

Borne beat against my chest like a second heart. “Borne.”

Names of people, of places, meant so little, and so we had stopped burdening others by seeking them. The map of the old horizon was like being haunted by a grotesque fairy tale, something that when voiced came out not as words but as sounds in the aftermath of an atrocity. Anonymity amongst all the wreckage of the Earth, this was what I sought. And a good pair of boots for when it got cold. And an old tin of soup half hidden in rubble. These things became blissful; how could names have power next to that?

Yet still, I named him Borne.

From BORNE. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2017 by Jeff VanderMeer.