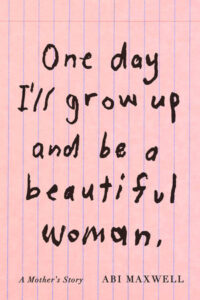

Books Have No Gender: On Being a Small Town Librarian While Raising a Trans Child

Abi Maxwell: “This town felt so conservative, its social norms so crushing. I needed someone who would help me swim against them.”

When our daughter was two—and still known as a boy—and I was a handful of years into my position at the library, the children’s room needed a new librarian and I needed more hours. It wasn’t a position anyone would have envisioned for me—I wasn’t animated and sociable, like all the previous children’s librarians, and I didn’t do crafts. But I cared deeply about literacy, and having a child meant I was learning a lot about children’s books. I moved downstairs, to the children’s room, where a woman named Lisa already worked. When she’d first moved to town from just outside New York City, she’d shocked me with her personality, which was so far from the reserved New England character I was accustomed to.

“We should go out sometime,” she’d said the day we met. “What do you like to do? We could go for a drink? Or dinner? Give me your phone number.”

Her nails were professionally manicured, her clothing bright. She was in high heels in the afternoon, and she had a large diamond on her finger. I was dumbfounded. “I really don’t go out,” I said pathetically.

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll work on you.”

She’d started working in the children’s room soon after that, teaching Spanish to elementary kids and leading a music and movement group for toddlers. We could hear her through the whole library while she taught, blasting music, singing children’s songs, laughing. Sometimes she’d parade the children right upstairs through the quiet adult section, drums and bells in their hands. She and I were so different, and when I moved into her workspace, my academic approach collided with her joyful one and neither of us knew how we would make it through. We bickered about where the books should be shelved, how the story times should be run, what the volunteers should do. We bickered about everything, and sometimes we got so frustrated that we drove each other to tears.

But eventually, something emerged through all our differences: we loved books and we believed in their power. We were in an insular town, and when she and I chose books for the library, we chose the ones that would expose the kids to a larger world. If our director didn’t purchase them, we filled out little paper slips to request them again and again. We made it our mission to diversify the collection. We believed it was the best thing we could do for the children of our community, and we learned to work together for it.

*

My grandmother had passed away by the time I worked in the children’s room, and Paul and I had used every last dollar we had—including the forty thousand dollars in government bonds I’d inherited from a great-aunt in Chicago, and the cosignature of my mother—to purchase her house. For a few years after we bought the house, Paul stayed home with our daughter while I worked in the day, and at night he went to a local restaurant to bake. They weren’t easy years. Something had happened to Paul’s hip—we didn’t yet know what—that made walking painful on most days, and nearly impossible on some. Also, he missed the west, and working a low-wage job in a rural restaurant was taking its toll on him. It became a growing seed of discontent between us—he dreamed of returning to Missoula and made passing comments about being stuck in New Hampshire because I wouldn’t leave the lake; and I snapped that if he wanted to go back west, he needed only to take the initiative to make it happen.

In truth, we both knew we didn’t have the energy. We were so tired. Our child had spent the first year of her life waking up every hour, and by toddlerhood she still had not progressed to anything even close to a full night’s sleep. We understood that she was different; I’d read every parenting book I could get my hands on, and nothing added up. She hit us, threw objects at us, hit herself in the head. She had not spoken until the age of two, and she rarely responded to her name, but by four she was putting together robots and snap circuit kits made for someone twice her age.

She would use only one particular spoon, one particular fork. My father had gifted her a garbage truck when she was three, and for two entire years she had played with that truck and nothing else. She meticulously cut paper to put in toy trash cans, and then she spread the cans around the house to drive the truck to pick up the trash and empty it into the toy dumpster. For her fourth birthday, she asked friends to bring garbage so she could send it down a chute and sort it. She loved Halloween not for the candy but for the wrappers. She mystified us.

In those early years, Paul would put her in the bike carrier and pedal her down to the children’s room for story times and library programs nearly every day. She did okay there so long as she could have the same exact cushion every time. But if the space was too crowded, she would become overwhelmed, cover her ears, and dart around in a panic. Sometimes, as I read a story aloud or glued googly eyes onto construction paper, I would watch out of the corner of my eye, heart breaking, as my husband carried our screaming child out of the library because she had begun to melt down.

But the children’s room was still a home to us, as it was to other regulars like us—families that came to all the library programs and checked out mountains of books each week. One was a girl our child’s age and her dad, and he and Paul gravitated to each other. His name was Eric, and soon he became our first real friend in town, the kind who would come over for an afternoon and unexpectedly stay all the way through dinner. Eric’s wife, Robin, traveled often for work, so it was some weeks before I met her. He’d told me a little about her, though—I knew she loved to play video games, and I knew she worked in finance; I knew we didn’t have much in common. Eric was easy for me—he liked to read and draw, and to talk about the process of making art. But when Robin first came over, our conversation was stilted. We seemed to have nothing to talk about, not until we landed upon what it looked like to raise a girl.

We both knew what we were really discussing—my child, known to the world as a boy, who put the princess dress on every time she visited.“She’s only three,” she said about her daughter. “And there’s already so much shit about body image everywhere.” We were sitting on the old couch I’d bought for fifty dollars when the library was getting rid of it, in the small room whose layout I never could get right. Robin worked for Mercedes-Benz, which meant she drove one, and I’d felt shy about the state of our house and our clear lack of wealth. But she had a relaxed way about her. She’d brought a bottle of Coke for herself and laughed at the salad we’d made, filled with random nuts and seeds and dried fruits from the back of the cupboard. “Eric warned me you all ate like hippies,” she said. Of her daughter she said: “There’s so much shit about what she’s supposed to like and not like.”

Of course I knew what she meant, and it existed for my child, too, though in a different form because we still thought we had a boy. There was a dress-up bin at the library, and when my child put the princess dress and plastic high heels on—as she often did—people stared. When boys in the children’s room tried to check out picture books with mermaids or princesses, their parents told them to put them down because they were for girls.

“It’s so stupid,” I’d said to Lisa once. “All this gendered stuff.”

“I don’t know,” she said, without looking up at me. We were in the back workroom, the story time crowd just cleared out. I noticed a shift in her—and she, surely, in me. We had come to know each other well; we knew that we were both strong-willed, and we could recognize when our bodies tensed and our voices became a little more forced—a warning that our deeply held opinions were about to bump up against one another. “I wish I had a girl,” she said. “I would love to dress her up like a princess.”

“But these parents who don’t let their boys check out princess books. It makes me sick,” I said. I knew I was speaking forcefully, knew I was attempting in my tone to leave no room for argument. And we both knew what we were really discussing—my child, known to the world as a boy, who put the princess dress on every time she visited.

Lisa kept her attention on the pile of cardstock in front of her. She was getting ready to cut out shapes for a craft. She lovingly made elaborate crafts with the kids, the kind she hoped they’d save for years. It wasn’t my style to do that—I tended to just throw a pile of playdough or fingerpaints on the table for them. “Sure,” she said as she sorted paper. “But also, I really appreciate gender roles.”

I didn’t press it. She was my friend. In many ways, she and I had seen the worst of each other, and we had come out the other side with a loyalty to each other despite our differences. But when I heard Robin question gender roles, I felt an immense relief. Compared to the liberal college city Paul and I had moved from, this town felt so conservative, its social norms so crushing. I needed someone who would help me swim against them.

__________________________________

From One Day I’ll Grow Up and Be a Beautiful Woman: A Mother’s Story by Abi Maxwell. Copyright © 2024. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.