Bombing in the Breadline: A Day in the Life of the Average Gazan

Ali Abu-Zayed Recounts His Experiences and Those of Others Enduring Starvation, Displacement and Genocide

It was a quiet night of genocide in the Gaza Strip. The clock showed 3:30 AM. I was deep in sleep, something we’d been deprived of for many days since the war began, when my wife, heart of my heart, woke me in a hushed voice:

“Ali, Ali! Get up so you can get a place in line at the bakery. You can sleep when you get back. God give you strength!”

I looked at her and got out of bed, thinking to myself, We can’t even enjoy a night’s rest anymore. I went to the bathroom to wash and perform ablutions, but there was no water. I remembered that I’d not filled the tank because Abu Jamil, the water-truck man, hadn’t come yesterday. The municipal water had been cut off from our area for some time because of a lack of fuel. I used a bottle of drinking water for the ablutions, got dressed, and walked to the bakery not far from our home.

The men in line were talking about the state of things—what we had come to, our people’s suffering, and the genocide that has swallowed us all.

Despite the relative calm, fear and caution clung to me. I quickened my pace to secure a good spot at the front of the breadline, hoping to return quickly to get the rest of my sleep.

The line was already full of people by the time I arrived. But I told myself, It’s okay, there aren’t that many ahead of me. I’ll wait for Hajj Dhiyab, the bakery owner, to arrive and distribute numbered tickets.

The sky was clear, and the air was fairly warm. The men in line were talking about the state of things—what we had come to, our people’s suffering, and the genocide that has swallowed us all. When the call to the dawn prayer rose into the air, I prayed right there in the street to keep my place in line, then returned to chatting with the guys.

There was a young man I hadn’t seen before, a stranger in our neighborhood. He was tall, wheat-skinned, with long, wild hair, like it hadn’t been cut in ages. His name was Faisal. He was talking about the misery of his displacement. He was from Gaza City, but the genocide forced him to flee south. He started telling me about the hardships he’d faced on his way down, and I was so absorbed in his story that I ignored the others around me.

Faisal recounted a horrific experience during his family’s displacement, when they were stopped at the Hallaba—a checkpoint the Israeli military had set up for fleeing Gazans. He spoke of the bitterness of what happened, “When it was my turn to cross, an Israeli soldier told me to move to the left. Everyone who was stopped there experienced every sort of humiliation, pain, and degradation. An Arabic-speaking soldier approached, demanding ID, then he ordered me to strip.” Faisal fell silent, tears in his eyes.

I whispered, my skin crawling, “Did you take it all off?”

“Down to my boxers. Without hesitation. I knew any hesitation could cost me my life.” He went on, his voice heavy with grief as he recalled the scene, “I took off my clothes piece by piece, trembling in fear.”

The breadline had grown longer, and young men were jostling to secure a place. I avoided the pushing—Hajj Dhiyab hadn’t yet arrived to distribute the numbered tickets. My attention stayed fixed on Faisal. He went on.

“The soldier tied my hands behind my back and blindfolded me as I kneeled. Then he left. I started thinking—what now? will they arrest me? kill me? let me go?” Faisal’s face twisted, his voice cracked, and he swallowed hard before continuing. “I was mostly worried about my wife and child—he’s not yet four. They’d crossed the Hallaba while I was detained. My wife is from Gaza City and didn’t know anything about the southern area. I remained in the same kneeling position for what felt like forever. I couldn’t move at all, terrified of meeting the same fate as others who’d been detained.”

He paused, gathering his thoughts, “I don’t know how much time passed while I was like that. Eventually, a soldier came and returned my ID, removed the blindfold, untied me, and ordered me to go south immediately. I grabbed my clothes and ran. Didn’t look back, and crossed the entire distance nearly naked, in front of the crowds of displaced men, women, and children, before I could put on my clothes.”

Faisal was careful to lower his voice when he was telling me about his nakedness. He cupped a hand over his mouth, afraid others would hear. He went on, “And that’s when the search began for my wife and son. I pulled my phone from my pocket and tried to call her. No answer.”

My eyes scanned the faces around me, all of them powdered in ash. I was looking for Faisal. I don’t think he had finished telling his story.

In the meantime, Hajj Dhiyab had arrived and begun distributing numbered tickets to lessen the chaos in the line. I had been waiting for hours. I took my number and went back to Faisal, still tuned to his story.

Then. Suddenly. An explosion.

The blast was thunderous, swallowing the place. Screams rose one after the other—“Medic! Help!” We didn’t know where they came from. The sky was covered with dust. We couldn’t see anything.

When at last the cloud of dust and smoke began to settle, we looked around for each other in panic. People ran wildly, calling out for their sons and brothers who’d been in the breadline—most of them young men, boys, children. A distant siren grew louder. I tried to gather my senses, to comprehend what had just happened.

It turned out that the Israeli annihilation planes had struck a house next to the bakery.

My wife came running, searching for me. She pulled me into her arms. I was covered head to toe in dust. I could hear her heart pounding in terror as she wiped the grime from my face with her warm hands.

“Thank God you’re safe, my love,” she said. “Come on, let’s go home. Forget the bread!”

My eyes scanned the faces around me, all of them powdered in ash. I was looking for Faisal. I don’t think he had finished telling his story.

__________________________________

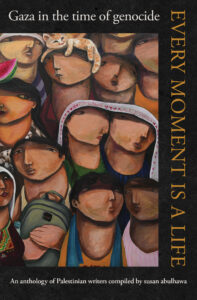

From Every Moment Is a Life: Gaza in the Time of Genocide, edited by by Susan Abulhawa with Huzama Habayeb. Copyright © 2026. Available from Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Ali Abu-Zayed

Ali Abu-Zayed, a graduate of the Bachelor of Arabic Language and Media from Al-Azhar University, writes content, is a community and media activist, and is interested in environmental issues and human sciences.