Bodies Fall, Not Ideas: On the Zero Line and the Urgency of Preserving Gaza’s Culture

Maya Al Zaben on Literature as Resistance

In Gaza, the libraries are gone. We’ve all seen it on our phones, even as censorship continuously prevails. The schools are gone too. What survives, what has always survived, is the oral archive. The stories passed hand to hand, ear to ear, breath to breath. Edward Said reminded us, decades ago, that marginalized people must seize back the right to narrate, to produce what he calls “narrative evidence” when official accounts fail or disappear.

When books burn and people vanish, Palestinian voices still insist on existing. There’s a famous Palestinian saying, albeit much more powerful in its original Arabic, that is the thesis of On the Zero Line, a collection of essays and poems written in the immediate aftermath of Israel’s invasion of Gaza in October, 2023: Bodies fall, not ideas.

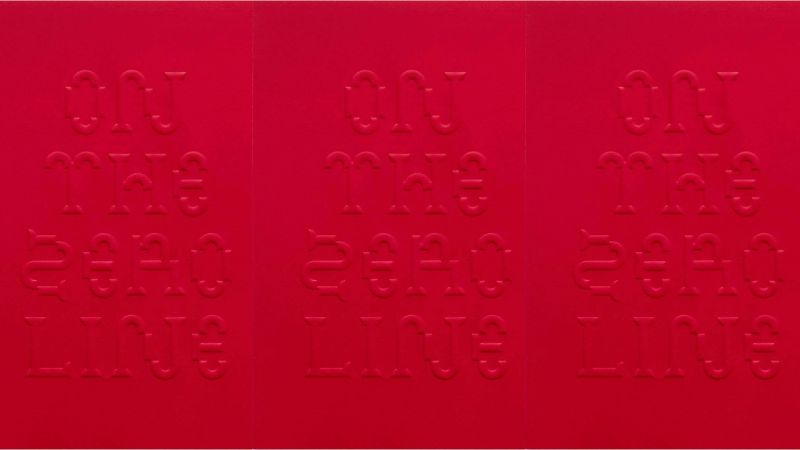

That the book exists at all feels miraculous. On the Zero Line, published by Slow Factory and Isolarii, compiled by Tariq Asrawi of the Tibaq Publishing House in Ramallah, and translated into English by Samuel Wilder. Sadly, the publishers cannot now confirm the whereabouts of every writer in the anthology. That alone tells you everything.

In a moment engineered to destroy both people and their memory, the one thing the occupier cannot take away, Western literary institutions have taken the position to suppress anything that utters the word “Palestine.” Panels have been canceled and a single mention of Gaza can revoke a book tour. Manuscripts delayed because “now isn’t the right time.” A phrase that really means “we don’t want the backlash” and “we definitely don’t want literature that names the thing happening in real time.”

On The Zero Line matters now because we are witnessing, in real time, not only the destruction of human life in Gaza but the systematic dismantling of its cultural landscape. One can call it a pushback against the idea that Palestinian life is only legible after the fact.

In one entry, novelist Ahmad Issa begins with a brutal, sarcastic refrain: We are terrorists. That is what they call us, and certainly. I have no choice but to believe their narrative. He goes on—surely the Zionist media machine knows more than I ever could. He jokes—darkly—that he must accept that his wife, who lovingly prepares maqluba, is a terrorist, and that her maqluba must therefore be a weapon of mass destruction.

Maqluba, also known as the “upside-down” dish to Palestinians, is a fragrant, layered pot of rice, spiced vegetables, and tender meat that’s flipped dramatically onto a platter so it lands in one perfect, steaming tower. Because the Zionist narrative has become so normalized, so globally absorbed, Issa describes the psychic violence of being conditioned, even as a Palestinian, to doubt himself. To wonder if the simplest acts of care, like a home-cooked meal of maqluba, are somehow criminal. It’s a dark satire of the “everything is Hamas” logic pushed by Zionist media, showing how absurdity becomes propaganda, and how propaganda becomes internalized harm. He’s describing the intimate damage of internalized erasure.

On The Zero Line matters now because we are witnessing, in real time, not only the destruction of human life in Gaza but the systematic dismantling of its cultural landscape.

To understand the urgency of On the Zero Line, one must understand the long lineage of Palestinian archival destruction and epistemicide, the killing of knowledge, as a weapon of settler colonialism. In 1948, as villages were depopulated under the Nakba, the newly formed Israeli army looted an estimated 70,000 Palestinian books and cataloged them under the sterile euphemism “Absentee Property.” Many of those books remain locked in Israeli institutions, misfiled as orphaned objects of “a vanished people.”

More recently in 2023 and 2024, airstrikes destroyed the Central Archives and Library of Gaza. The Rashad al-Shawwa Cultural Center, long a home for readings, lectures, theater, was also obliterated. Universities, literary salons, youth writing programs were gone or displaced.

One of the first things I noticed in the book is that many of the writers in On the Zero Line begin with questions, or return to them constantly. Questions of uncertainty. With the kind of thinking that happens when life has been whittled down to waiting: waiting for a signal, for news, for water, for morning, for the next airstrike.

It’s one of the realities of living under genocide, how the mind reshapes itself when so little is in your control. In Gaza, you don’t get to decide whether the internet is on or off, whether your phone has service, whether your home still exists by the time you return to it. And in that suspended state, the mind turns inward. It circles its own questions. Maybe that’s why so many entries are filled with Why? or How long? or What will happen to us? Because during war, and when the world narrows to danger and waiting, what else is there but questions?

The anthology becomes a guideline of questions not really expecting an answer, but needing to ask anyway.

Hesham Abu Asaker, one of the writers in the book, asks: “Do you see us, world? We see your forgetting as you silently tally our dead. Are you watching, or just admiring some aspect of our “heroism”, seduced by what is said?”

Razan Abu Asaker wonders, “How can death be so outrageous? How can it rip the heartbeat from a person’s chest with such ease?”

And A.A. Salama with the most simple of questions, “What’s wrong?”

These are questions that don’t let the reader look away.

And to translate Gaza into English is to intervene in the world’s literary bloodstream. It interrupts the old colonial idea that Palestinian writing is supplementary, regional, “conflict literature,” always shelved next to tragedy rather than…normalcy.

And in the context of siege, translation stops being a scholarly act and becomes a logistical one. Like an act of smuggling. These writers can’t travel, but their sentences can. Their metaphors can. And their memories absolutely can. These poems slip under the door of the blockade, cross through fiber-optic cables, before landing in an editor’s email inbox thousands of miles away. Literature becomes the one border-crossing still possible. The only form of mobility no army has figured out how to fully restrict.

On The Zero Line is literature that has become its own archive not physically housed in buildings, because those buildings have been flattened, but housed in bodies, and in this case, a little red book.

For all the horror of the present moment, these stories cannot be locked away. They do not exist only during moments of catastrophe, nor do they require the dominant narrative of the media and of our governments to grant them meaning or legitimacy.

Which means the reader becomes the library. The screen becomes the library. Every person who encounters this book becomes responsible for carrying it forward and amplifying the voices of those who cannot use their own.

Maya Al Zaben

Maya Al Zaben is a Palestinian-American fashion writer and researcher based between New York City and San Diego. Passionate about community, divine purpose, and bringing people together, her work mostly explores the intersections of fashion, culture, and identity. A Parsons School of Design alum, she was featured in Vogue as an astrological visionary and in Harper’s Bazaar as a rising star in fashion commentary, among other publications.