Bob Dylan’s Superpower is That He Doesn’t Get Embarrassed

Ron Rosenbaum on the Icon and the Enigma

To be caught in the spotlight of our pretensions is the worst kind of embarrassment there is.

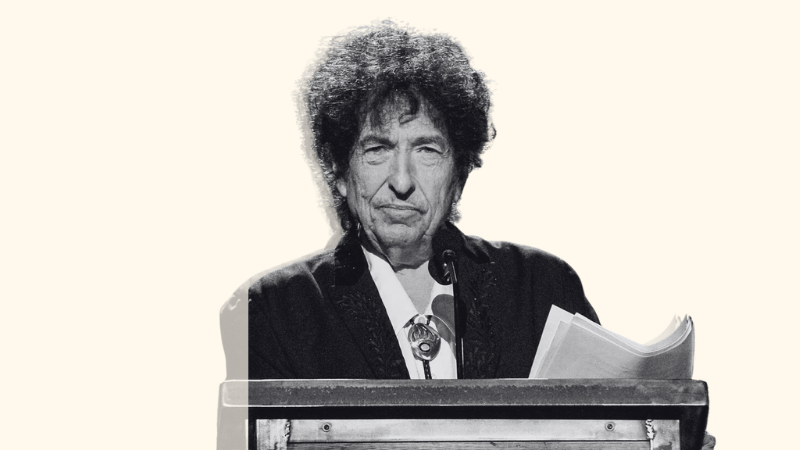

And so, one thing I found notable in the years I spent writing a biography of Bob Dylan and his poetic songwriting was the almost complete absence of embarrassment. The guy may be the most self-assured artist on the planet. The crowds booing and jeering him—the uproar when he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival, the furor over the same on his follow-up English tour…Dylan just looked upon the mob calling for his head with a pitiless stare and told the band to turn it up.

He never expressed embarrassment over the dismal commercial failure of his would-be cinematic masterpiece, Renaldo and Clara, even after the film’s financers, Warner Bros., warned Dylan that the film’s nearly five hour running time would ensure its failure (which would prove true). Dylan insisted that the film needed every frame. And who knows, art history may vindicate him. (I argue it will in my book.)

Then there was his claim that Jesus visited him in a Tucson motel room to gather up his very soul, which led to Dylan’s born-again period—for three years, Dylan concerts were 90-minute ranting, apocalyptic attacks on his own stunned devotees. But for Dylan, going from Jew to Jesus freak—however slack a Jew he’d been—was no more questionable or embarrassing to him than going from acoustic to electric. He never sounded more sure of himself than in his newfound righteousness, and there was no embarrassed self-reflection later, after Jesus’s spell on him was broken.

Leonard Cohen dismissed the whole affair, saying, “Giving Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize is like pinning a medal on Mount Everest that says, ‘Best Mountain.’”

So how to explain Dylan’s seemingly stunned sense of embarrassment at the news that he’d won the Nobel Prize for Literature in October, 2016?

He’d won numerous prizes and awards over the years, but none of them had seemingly paralyzed him the way the Nobel had, especially The Decision it meant he had to make: whether to accept it or not.

Leonard Cohen dismissed the whole affair, saying, “Giving Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize is like pinning a medal on Mount Everest that says, ‘Best Mountain.’”

But according to a spokesperson for the Academy, Dylan was “in the great English tradition stretching from Milton to Blake and onward.”

Regardless, for three weeks Dylan didn’t respond at all to the announcement of the award, nor to the customary invitation from their Royal Majesties, the King and Queen of Sweden, to come to Stockholm to accept the coveted Prize in person.

For three long weeks that began to seem rude or impertinent, as if the Prize hadn’t been announced, as if a king and queen weren’t waiting for his answer, Dylan said nothing about the award. Nada. He stayed on the road, playing the small-town arenas he favored at the time.

Finally he found a way that some might say split the difference. Or exacerbated the impertinence. He issued an anodyne statement thanking the Swedish Academy for the honor but declining the Royal invitation from their Swedish royals to actually show up in Scandinavia to accept the award—because, he said, he had “other commitments.”

It was the perfect Dylan-esque putdown response. Using the formal language of propriety to mask a slap in the face. (Some said Sweden was a problem for him because the storied Swedish neutrality in Hitler’s war fraudulently masked the Swedes supplying iron ore and armaments to Hitler’s Wehrmacht.)

And Dylan continued to split the difference between politesse and reproof when it came to the potentially embarrassing hypocrisy the formalities of the Prize presented. For example, instead of appearing in person, he asked the state department to send someone from the American Embassy to read his brief speech for him.

What’s more, in a master stroke, when asked to perform a song for the assembled notables at the awards banquet, he instead sent Patti Smith in his place, to sing, accompanied by a full orchestra, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” (whose nearly interminable verses she forgot at one point and had to start over).

Still, the climactic development in the extended Nobel drama came six months later, when Dylan submitted to the Swedish Academy its final requirement (without which he wouldn’t have received the nearly $1 million in prize money)—an essay about the literature that had most influenced him.

It’s sad that this amazing essay has been almost entirely overlooked by Dylanologists, because it offers a skeleton key to something in my opinion quite essential about Bob Dylan.

But Dylan makes the point that it’s more than a book about the horrors of war—it’s a book about the failures of civilization.

After pro forma tributes to The Odyssey and Moby Dick, he focused with searing intensity on Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front.

“It’s a book,” Dylan wrote, “where you lose your childhood, your faith in a meaningful world, your concern for individuals. A book that leaves you stuck in a nightmare, sucked up into a whirlpool of death and pain.”

The book, which is about the life of an ordinary soldier in the trench warfare of World War I, was about being turned into “a cornered animal…There’s endless assaults, poison gas, nerve gas, morphine, burning streams of gasoline, scavenging and scabbing for food, influenza, typhus, dysentery, Life is breaking down…rats eating the intestines of dead men, trenches filled with filth and excrement…”

But Dylan makes the point that it’s more than a book about the horrors of war—it’s a book about the failures of civilization.

“All that culture from a thousand years ago, that philosophy, that wisdom—Plato, Aristotle, Socrates—what happened to it? It should have prevented this.”

Dylan’s description is a work of ferocious eloquence. An indictment of all Western Civilization for being a thin mask of civility and propriety failing to cover the ceaseless butchery beneath.

It’s a takeoff point for Dylan’s vision of the Inferno—a direct frontal attack on the authority and propriety claimed by the philosophers of Western Civilization and theology. It’s mindful of the “theodicy” I find throughout Dylan’s lyrics—the attempt to reconcile the prevalence of evil with a loving God.

As Dylan sang in Highway 61, “God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son.’ Abe said, ‘Man you must be puttin’ me on.’”

In my view Dylan turned the whole Nobel episode from what could have been an episode of embarrassment and hypocrisy into a way of opening his heart to the painfully aggrieved submerged subtext one could find beneath so many of his most resonant lyrics.

Which is what made Dylan Dylan.

__________________________________

From Bob Dylan: Things Have Changed. Used with the permission of the publisher, Melville House. Copyright © 2025 by Ron Rosenbaum.

Ron Rosenbaum

Ron Rosenbaum studied literature at Yale, and briefly at Yale Graduate School, before leaving to write. His work has appeared in Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Observer, and Slate, among other publications. His book Explaining Hitler, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year in 1998, has been translated into ten languages. Random House published a collection of his essays and journalism, The Secret Parts of Fortune, in 2000 and an anthology he edited, Those Who Forget the Past: The Question of Anti-Semitism, in 2004. He has been a member of the advisory board of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s publications project. He lives in New York City.